The government has proposed amendments to the State Bank of Pakistan Act, establishing its primary objective of stabilizing inflation in Pakistan. Idea is to specify the central bank’s objectives clearly, enhancing its accountability. Macro Pakistani believes the proposed changes are much needed and will not turn the SBP governor into a Viceroy. Providing SBP autonomy will help it become more focused on monetary policy and take away the quasi-fiscal responsibilities it held before. We will not discuss the amendments in detail but instead, discuss the significance of inflation in Pakistan, its potential causes and the role SBP can play in maintaining domestic price stability.

According to the World Bank, inflation tends to be lower in countries that employ an inflation-targeting framework and that have more independent and transparent central banks. In emerging markets, inflation-targeting countries have median inflation of 4.8% compared to others at 8.7%. Countries with independent and transparent central banks have median inflation of 5.5% compared to others at 8.6%. SBP, our central bank, will now explicitly target inflation in Pakistan with independence. Hence, we can expect inflation to trend lower in the medium to long term. However, in anticipation of the blame game that will ensue if inflation in Pakistan increases, Macro Pakistani will try to break inflation down and explain the part that SBP can influence.

Let’s get real (not nominal)

We have discussed the difference between real growth of GDP, which includes change in volume of goods and services and nominal growth, which includes both volume and price changes. First thing to understand is that price increases are not necessarily bad. In fact, controlled inflation is a sign of economic growth. As a consumer, if you receive higher quality goods and services, you would be willing to pay more. As a producer, if you know higher quality can get you a higher price, you will invest and improve quality to get that higher price. However, if the quality of your consumption does not improve but you are still forced to pay a higher price, you will not be happy. The higher prices will simply reduce your purchasing power without making you better off.

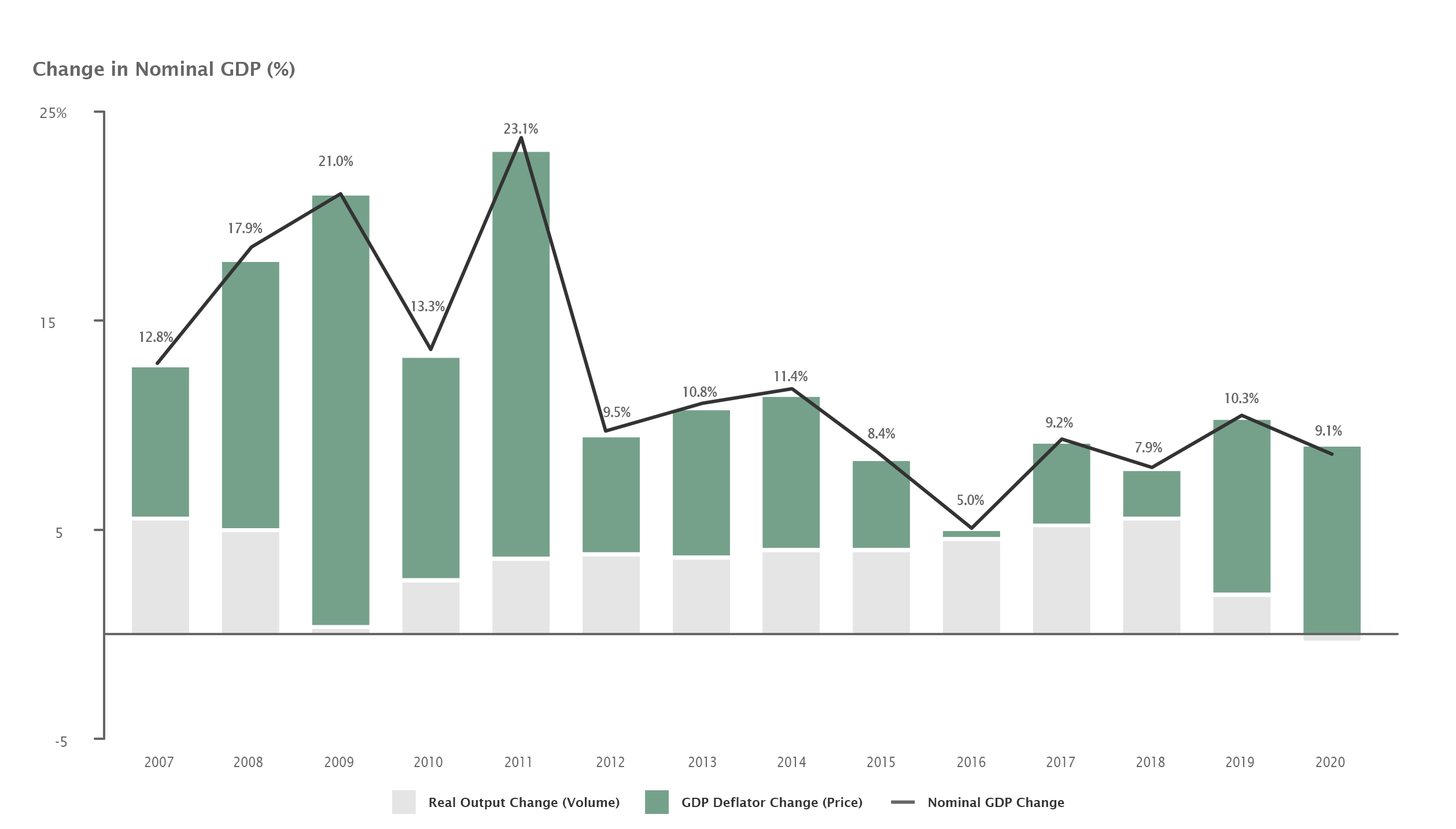

Nominal GDP growth from price changes has been higher than change in real output

Source: Pakistan Bureau of Statistics; MP Analysis

This story of eroding purchasing power is one that Pakistanis are all too familiar with. Between 2007 and 2020, incomes for Pakistanis (Nominal GDP) went up by 12% each year. But out of that, around 8.5% was taken away by price increases, while quantity of goods only went up by 3.5%. GDP Deflator is a measure of all price increases in the economy. Changes in the deflator (green) have exceeded real output growth (grey) for most years except for 2016-18. Since GDP is measured on an annual basis in Pakistan, the deflator is also an end-of-year estimate. To have more frequent updates on price, most countries use the Consumer Price Index as a measure of price changes or inflation.

Roti, Kapra aur Makaan

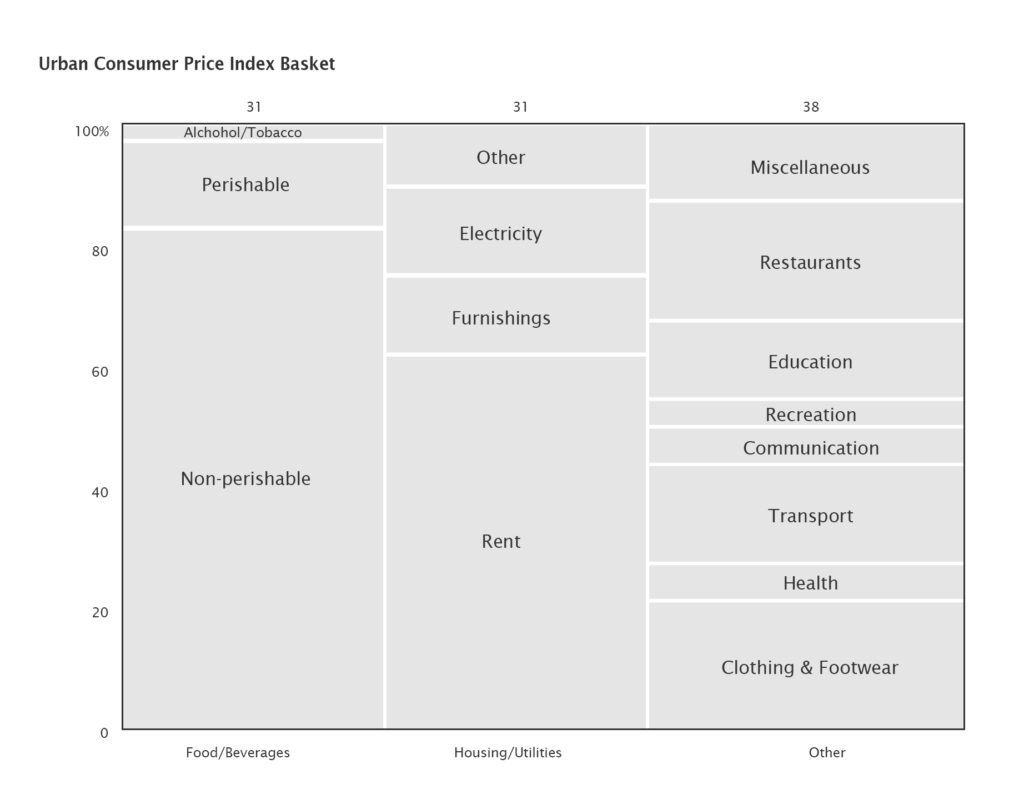

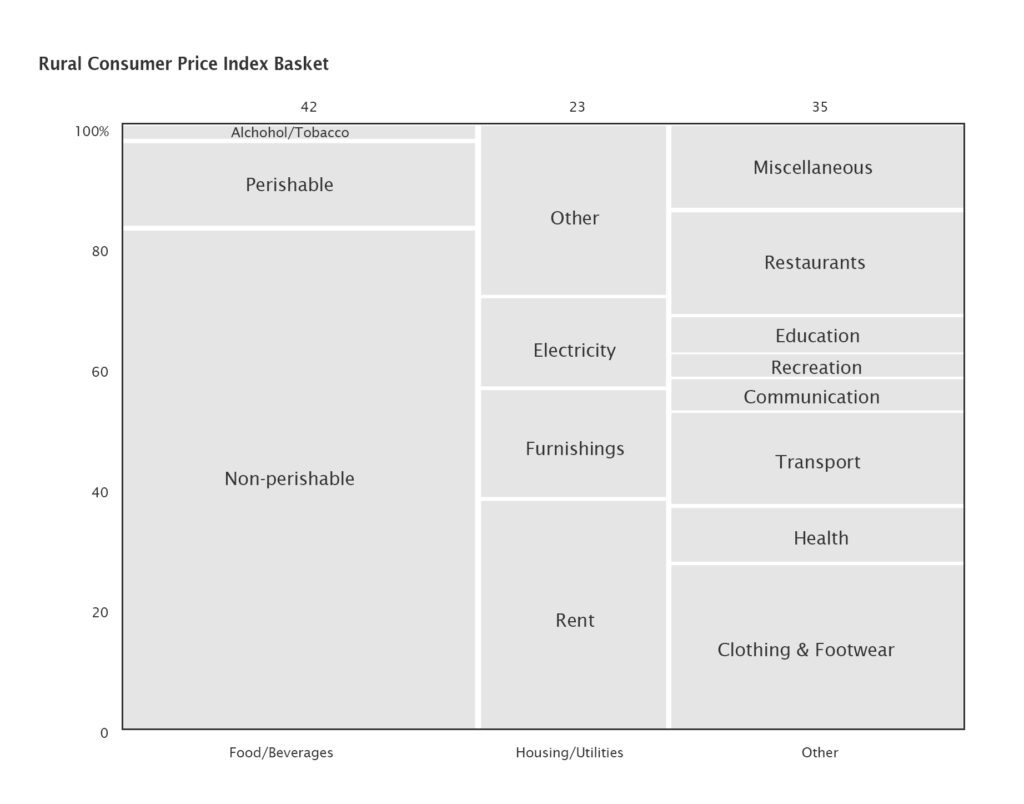

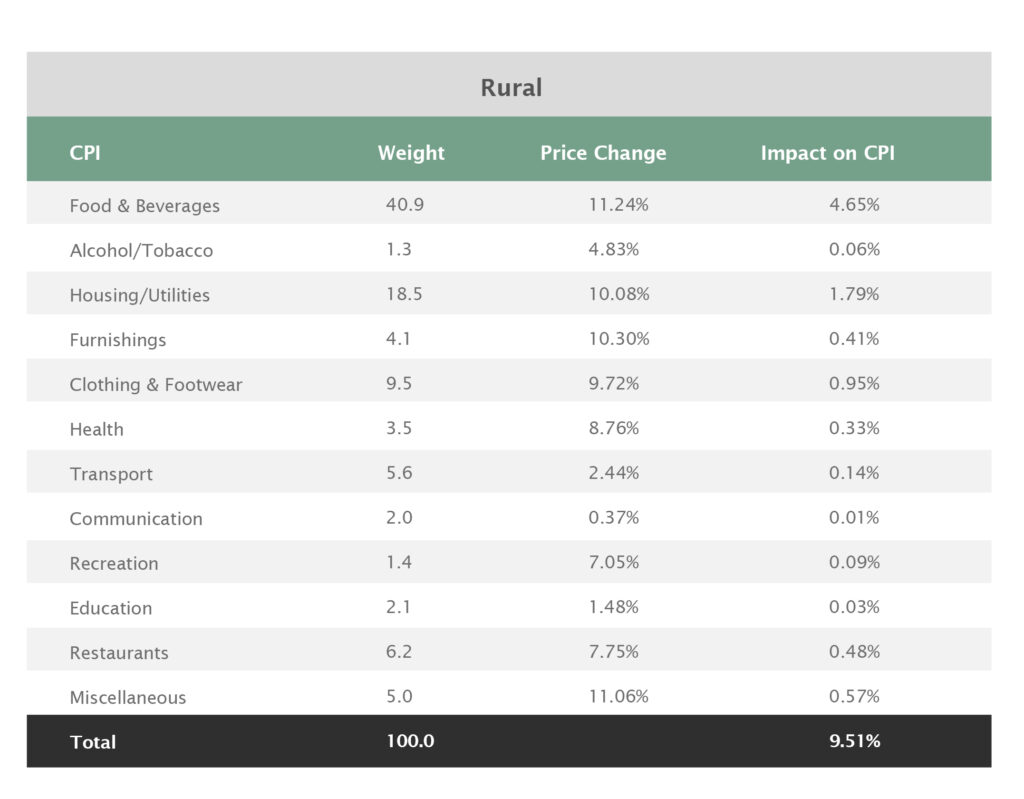

The Consumer Price Index takes into account price changes for different consumption baskets. Pakistan Bureau of Statistics checks what is included in a typical household’s monthly consumption. This typical household is different in rural and urban areas and is different in consumption across income levels. Hence, consumption baskets were estimated separately for all these categories in 2015-16 and since then price changes for commodities included have been tracked. These calculations are easier to understand with an example.

Consumer Price Index take into account price changes for different consumption baskets within urban and rural areas

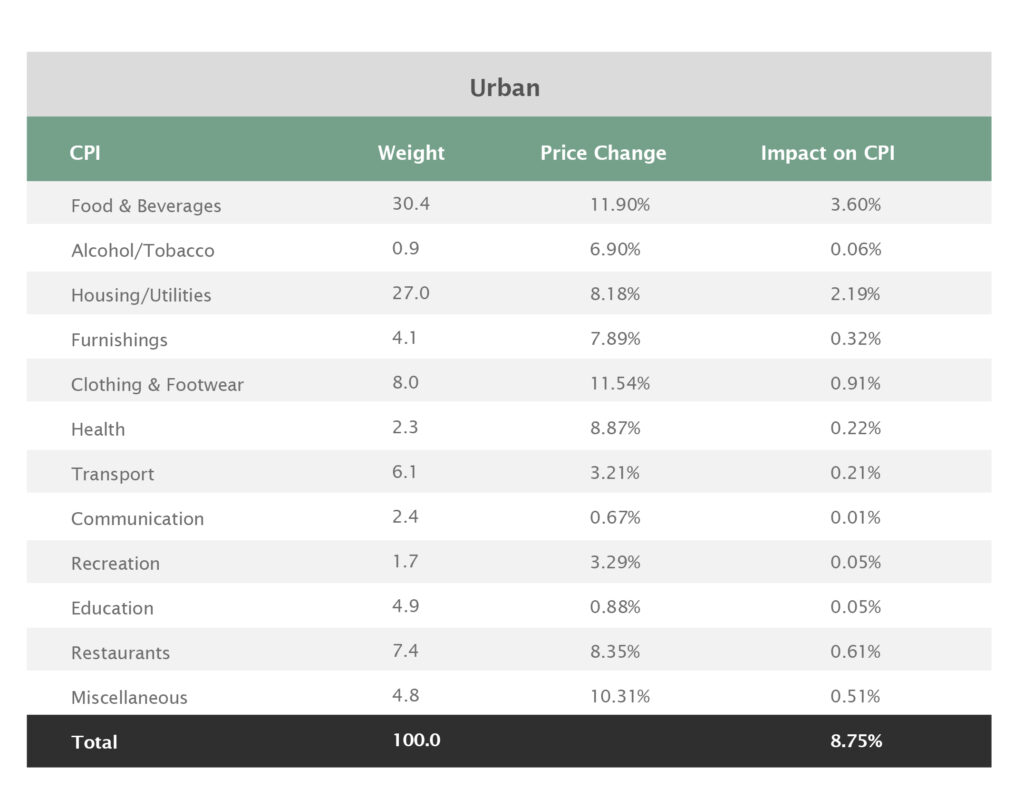

Consider an average urban household spending around 30% of their monthly expenditure on food, 30% on housing and utilities and the rest on other goods and services. The bureau surveys markets on a monthly basis to check for prices of typical food products, housing rents, electricity bills, clothing and even personal grooming services. Any price changes are multiplied to the weight of that commodity to calculate the impact on inflation. The annual inflation number, which is the output of this exercise, shows how much more the average urban household had to spend on the same basket of goods and services it bought last year. The latest numbers show that an average urban consumer had to pay 8.75% higher prices in March 2021 than they did in March 2020. This increase can be mainly attributed to the most heavily weighted items of food (+11.90%) and housing (+8.18%).

Impact on inflation is highest from the most heavily weighted food and housing categories in urban and rural areas

The same exercise is conducted for rural areas and then the average is reported as National Consumer Price Index. It is important to note that even though price changes are reported, a household’s consumption patterns might have changed since 2016. This is not captured currently in how Pakistan reports inflation. There are other kinds of price indices also measured, mainly Core (Non-Food/Non-Energy), Wholesale Price Index and Sensitive Price Index, which we will not discuss.

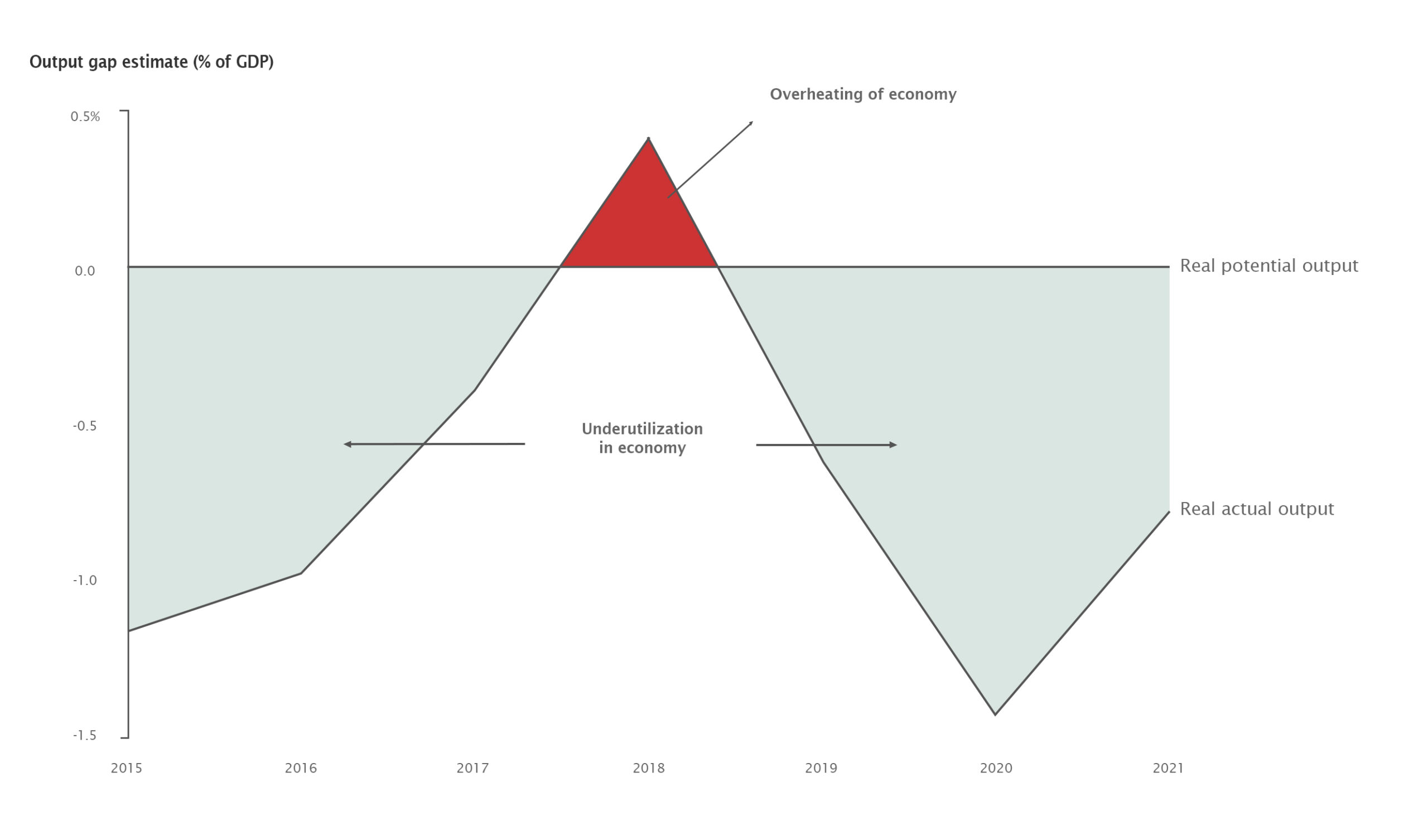

An overheating economy

Demand-pull inflation is caused when an economy’s production capacity cannot keep up with consumer demand. As a consumption driven economy, our consumer demand has been on the rise. This is driven by both population growth rate, with more mouths to feed, and a tendency to spend more on higher value goods to improve quality of life. As demand for goods and services in the entire country, known as aggregate demand, rises, prices go up. Note that this will mostly be the case if there is no excess supply in the economy to provide those goods. If the country is productive and can cater to the needs of the people, demand-pull inflation will remain relatively low. This difference between the actual output a country produces and the potential it can produce is the output gap.

When actual output is above potential output, demand pulls prices higher. The economy ‘overheats’ as demand becomes unsustainable for producers. When actual output is below potential output, there is room for the producers to supply the goods demanded without increasing price. It is quite complex to estimate, especially for a country like Pakistan where data is not as readily available.

Before 2019, Pakistan’s economy was on the path of ‘overheating’ with actual output exceeding sustainable potential output

Source: State Bank of Pakistan; MP Analysis

Even though the above chart shows year wise output gap, SBP estimates that if we were to consider quarterly numbers (which are not reported) the gap has been as high as 6% in the past. However, even with annual numbers it is clear that Pakistan was on the path of overheating prior to 2019 and that was followed up by demand-pull inflation.

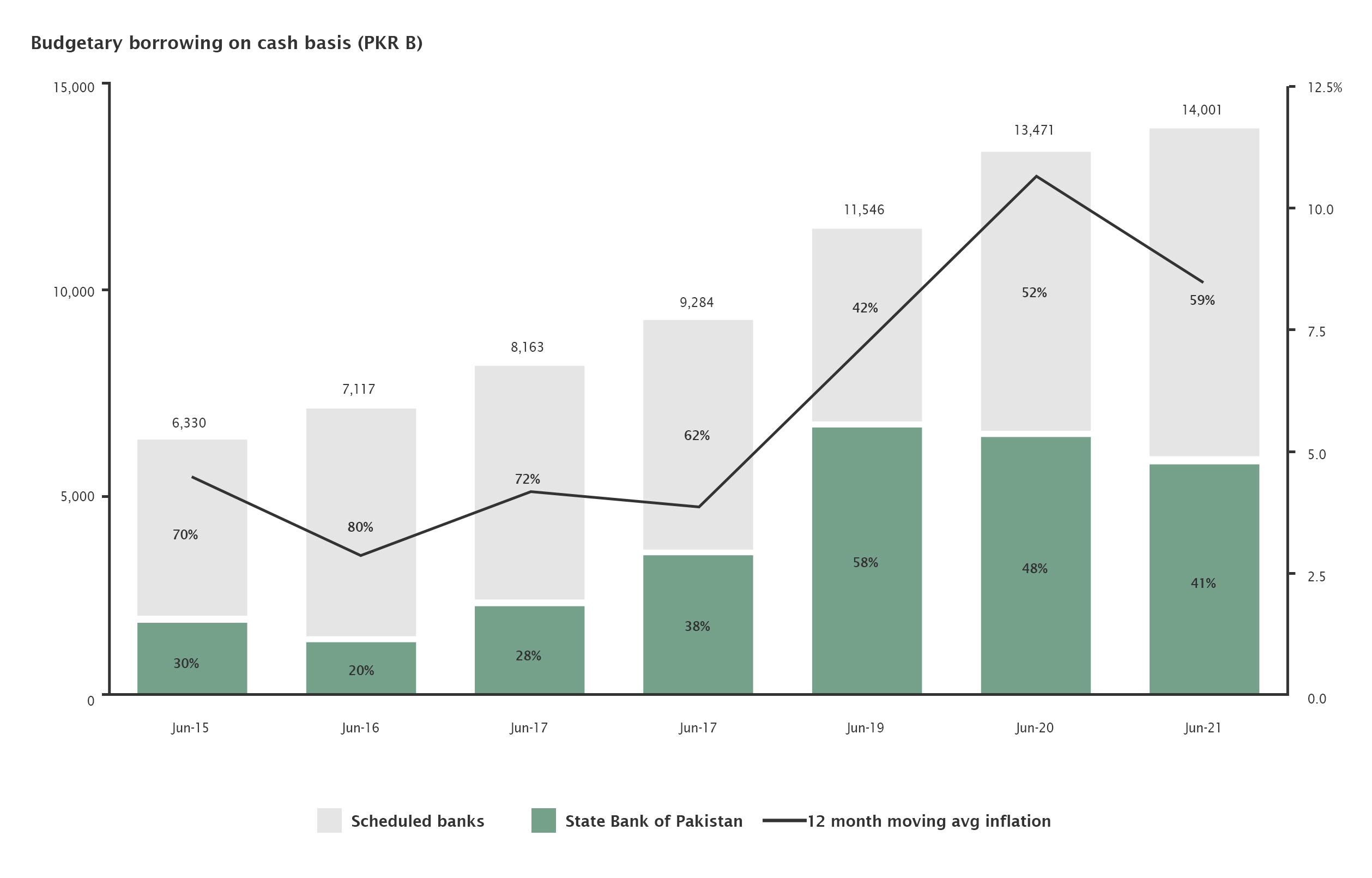

Government causes inflation

If the State Bank of Pakistan had to control this form of inflation, it would increase interest rates in the country. As interest rate rise, cost of borrowing increases, making both credit and investment more expensive. At the same time, consumers might find it more attractive to save, reducing their consumption. This is meant to cool down the economy. However, in Pakistan, depositors do not care much about the saving rate while private credit is less than 20% of the GDP. So why would change in interest rates affect aggregate demand in this country?

The answer lies in the fact that the government is the biggest borrower in Pakistan. Part of the overheating was caused by increased government spending fueled by cheap credit. Until 2019, the government had the ability to borrow directly from SBP. As SBP’s share of budgetary borrowing rose from 20% in 2016 to 58% in 2019, inflation more than doubled from around 3% to over 7%. This borrowing comes from the central bank printing more money which leads to an increase in spending and then demand-pull inflation. The continued rise until 2020 was partly a lagged effect of the rise in government borrowing in past years.

One of the key factors behind overheating was increase in share of budgetary borrowing directly from SBP, leading to rising inflation

Source: State Bank of Pakistan; MP Analysis

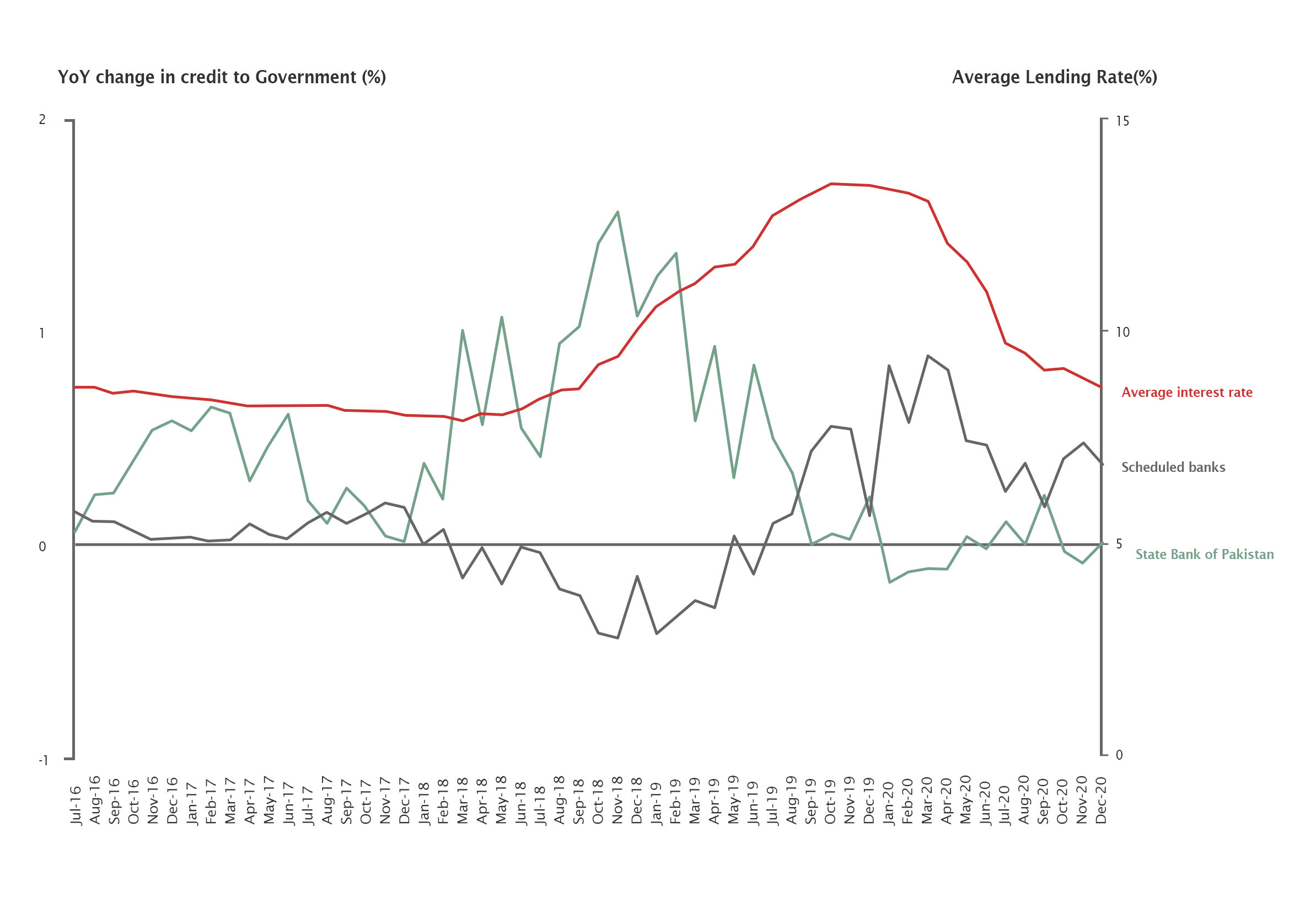

With an independent SBP targeting inflation, this would not have been allowed. Once reports showed a looming positive output gap, signaled by unsustainable levels of spending, SBP would have raised rates to reduce government borrowing, and control inflation. Even as the interest rate was raised, the government started increasing its share of borrowing from the politically controlled central bank. This is why when the IMF program started in July 2019, the policy rate was raised significantly and the government agreed to not take financing from SBP for budget deficits anymore.

Credit to government continued to rise through borrowing from SBP even though interest rates were raised in 2018

Source: State Bank of Pakistan; MP Analysis

What can SBP control

We mentioned two other types of inflation. Cost-push inflation occurs when aggregate supply of goods and services decreases because of an increase in production costs. This is the inflation most people are familiar with and it is the one that SBP cannot control. If the government increases the minimum support price on wheat to help farmers, the costs for the flour producer go up. This will lead to inflation. If the government increases electricity tariffs because of public misadministration, it will hurt consumers and lead to inflation. If the international price of oil goes up because there is a global supply shock and the government transfers this increase on to consumers, inflation will go up. The State Bank of Pakistan will not be able to do much here.

The last type of inflation is the wage-price spiral, which is a combination of demand-pull and cost-push inflation. If wages rise in an economy due to an increase in minimum wage or because the quality of labor and its productivity improves, they will increase disposable income for workers. With higher disposable income, demand for higher value goods will go up. This will cause demand-pull inflation. When prices rise, workers will ask for higher wages. This will lead to higher production costs and the cycle will repeat. The State Bank of Pakistan can stop this spiral to begin in the first place by controlling interest rates and reducing demand. However, it cannot control minimum wage increases that are dictated at a provincial level.

With SBP’s newfound autonomy, citizens should aim at understanding inflation more. They should differentiate between long-term demand driven inflationary pressures and temporary supply shocks. Interest rates and money supply that SBP can affect might curb demand-pull inflation but are ineffective against cost-push inflation. Providing the SBP autonomy will depoliticize interest rates and help us keep it accountable for what it can actually control.

If the bill passes successfully and the SBP does become autonomous, Would it be fair for one to expect that since they are able to focus more on monetary policies (as mentioned in the article), the exchange rate of PKR would rise against those of other major Currencies that we trade with? Or at-least will the Rupee become a bit more stable?

We would expect SBP to continue its practice of leaving exchange rate market based but intervening to avoid wide swings either up or down. Keep in mind that monetary policy instruments like policy rates also impact exchange rate. So if inflation goes up, and SBP is forced to increase interest rates, the PKR will gain in value as more foreigners put money in the country looking for higher yields.