A few of you might be confused as to why we are going from talking about investments and manufacturing to financing in Pakistan. The last post mentioned, in passing, that ‘money makes money’ but that statement in itself is not self explanatory. A small primer on banking would help understand this well and set the scene for why low financing also leads to low investment and hence low productivity.

Free money is nice money

Banks take money from depositors and lend to borrowers. If you have a savings account, you are paid a small profit on the money that you keep with the bank. If you have a current account, you are paid nothing and you provide the bank free money. Banks take money from both kinds of accounts and then invest it where they deem fit. Now obviously, the bank wants to get the cheapest money possible from you (think many current accounts) and then make the most profitable investments from that money. ‘Profitable’ here does not just mean the highest return. Banks mostly look at what’s called RAROC or Risk Adjusted Return on Capital.

RAROC basically shows a bank how much money they can make, given the riskiness of their customer. On one end, you have risk-less customers that pay decent money and you would want a lot of them. In our case, the government issues Pakistan Investment Bonds (PIBs), which bring somewhere between 7-10% profit. Bank takes zero risk and makes 7-10% from essentially free money.

On the other end, you have extremely risky investments that may or may not pay decent money. In our case, let’s take a new startup with an unproven business model. If it works, it can bring somewhere between 15-20% profit but if it doesn’t work, bank gets zero. Banks use complex risk calculations and determine how likely it is that the startup will fail. If the answer is more than 50% of the time, it is likely that the bank will just choose to invest with the government.

Money makes money

If the startup does not get the loan, it may decide not to make the investment it was going to make or may choose to take more time to generate cash through profits and invest later. According to the World Bank, only 8% of firms in Pakistan use banks to finance investments as compared to Bangladesh’s 20% and India’s 30%. This is important because loans help accelerate and improve the return on one’s investment.

If you were to buy a house for PKR 10 million from your money and the value went up by 50% after a year, your gain would be 50%. This is because the house you bought for PKR 10 million is now worth PKR 15 million. Now imagine if you did not pay for the house in full with your money. If you paid PKR 5 million yourself and borrowed PKR 5 million, your invested capital would be 50% while debt would be 50%. Now imagine if the value of the house went up to PKR 15 million. What would your gain be now?

Since you put only PKR 5 million of your own money and the value of the house went up by PKR 5 million, you would make a 100% profit! The bank does not share the upside in the value of the house since it only gets a pre-determined interest rate. Even if you were paying a 20% interest rate on the PKR 5 million you borrowed, your gain would be PKR 9 million which is PKR 4 million more than what you made when you took no loans. Yes, eventually you will have to pay back the debt but with time value of money (cash now is better than cash later) and tax benefits (interest is usually tax deductible), you will be better off.

Numbers are not nice

If this was too many numbers, take Macro Pakistani’s word for it: a certain amount of debt is good for profitability. However, banks in Pakistan have many risk-less investment options, since the government borrows a lot, which ‘crowds out’ private investment.

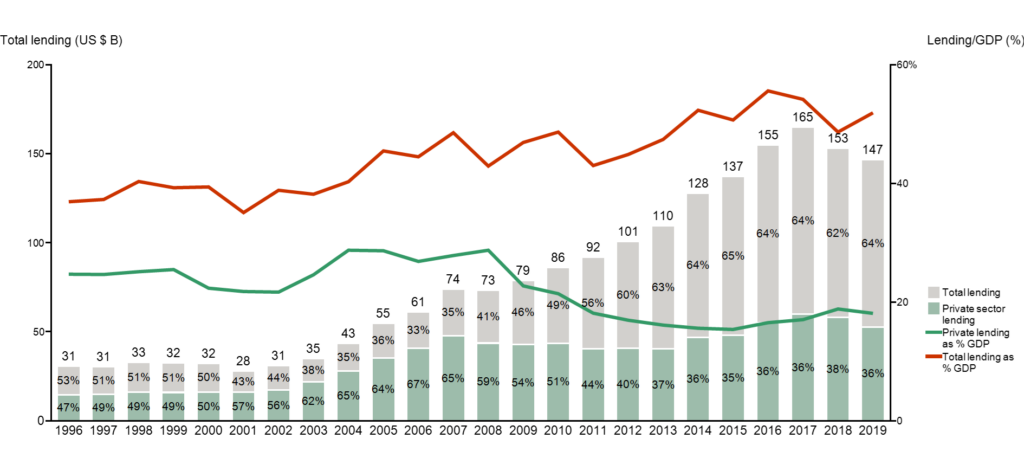

Total Financing in Pakistan (1996-2019)

While total lending has increased to over 50% of GDP (red line), less than 20% goes to the private sector (green line). Notice up until right before the Global Financial Crisis in 2008, private financing in Pakistan was on the rise. From an earlier post, you might remember that this was also the time investment in Pakistan was on the rise to about 20% of GDP. By 2019, private financing in Pakistan had fallen from 28.7% of GDP in 2008 to 18.1% and investment had fallen from 19.2% of GDP to 15.6%. All this while, government borrowing (grey bars) has been on a steady rise.

How Asia doesn’t work

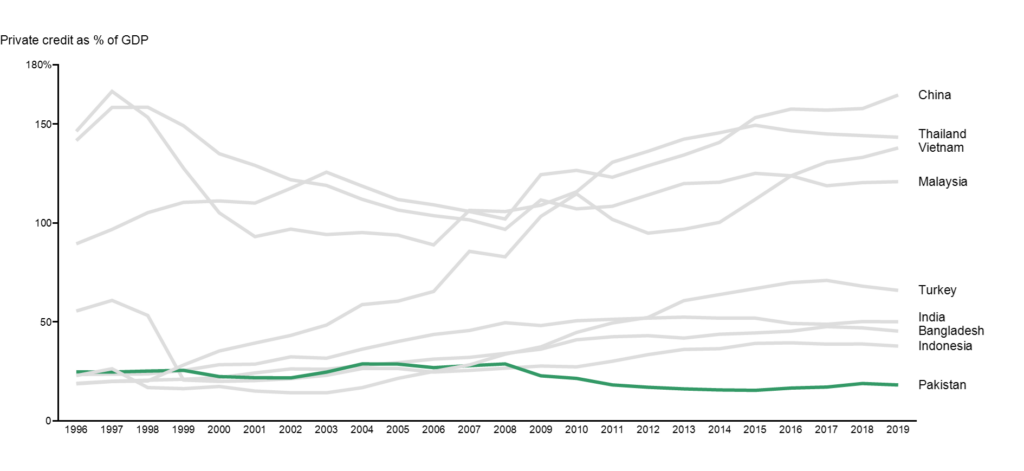

For a lot of the developing countries in Asia that we have mentioned, economic growth was fueled by growth in private credit. Over the last 25 years, share of private credit for all regional comparisons increased while it worsened for Pakistan.

Private credit in Pakistan vs. Global comparison (1996-2019)

Again, let’s not compare Pakistan to China, where the private sector alone borrows 165% of GDP, but India should be a good comparison. In 1996, private financing made up just over 24-25% of GDP in both countries. While the number has doubled to 50% for India today, it has fallen to below 20% for Pakistan.

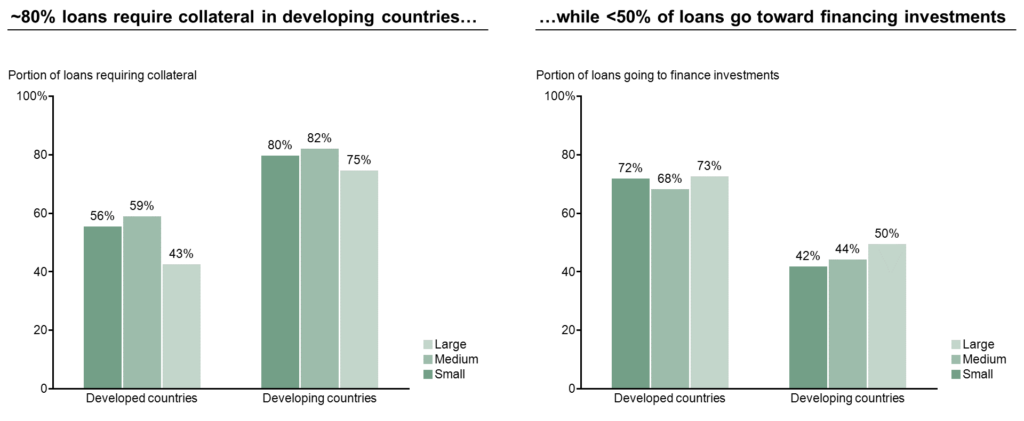

In addition to the government borrowing a lot, businesses also complain of excessive collateral requirements from banks but this problem is not unique to Pakistan. Regardless of size, banks in most developing countries ask for collateral for ~80% of loans as compared to less than 60% in developed countries. This is because, for an investment to make sense to the bank, they need to have some security that they can claim from you, in case your business goes bust.

Collateral requirements globally and impact on investment

If the startup that we previously discussed can provide some collateral (e.g. land) that the bank can seize if they default on their loan, it becomes less risky for the bank to lend. But now, the startup will take on less risky investments themselves after they almost guarantee return to the bank through their collateral. In developing countries, only 42% of loans taken by small firms go toward investment for this reason as compared to developed countries where the number is 72%. Size of firm matters little across both developing and developed countries, with the numbers varying only slightly.

Size does matter

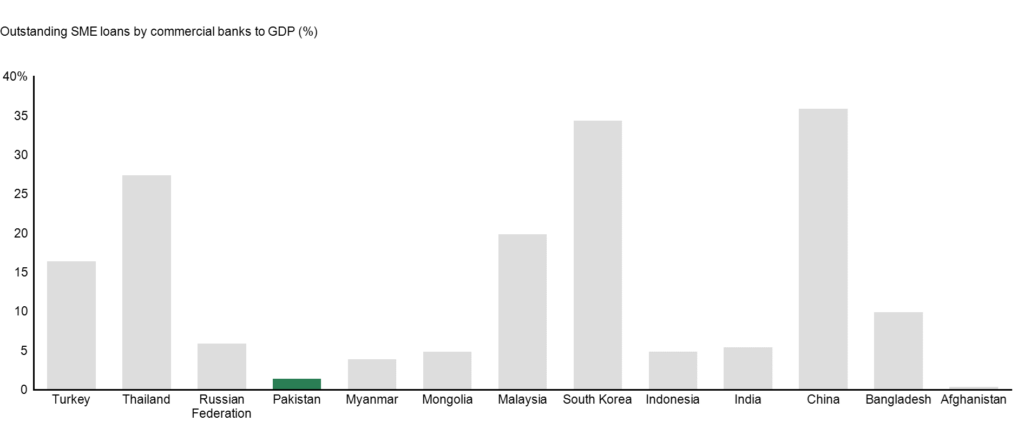

However, in Pakistan, size matters a lot more. Access to finance for Small and Medium Enterprises (SMEs) is comparable to Afghanistan and 4-6 times less than India and Bangladesh. SMEs are engines of growth for these economies and without finance, they would not have been able to invest for the future.

SME Financing in Pakistan vs. Global comparison

SME financing in Pakistan makes up 1.5% of GDP only as compared to India’s 6% and Bangladesh’s 10%. What this means is that out of all private sector financing in Pakistan (18% of GDP), roughly only 8% makes it to SMEs.

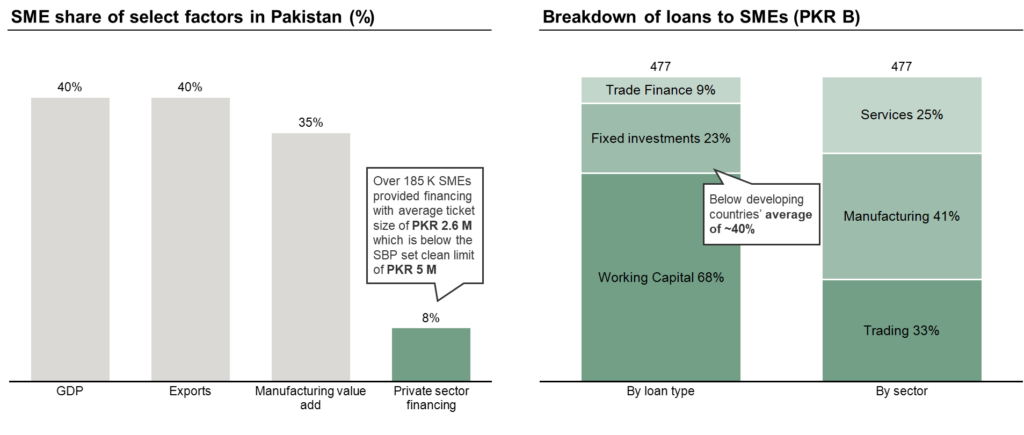

Importance of SMEs and current state in Pakistan

This is despite the fact that SMEs make up close to 40% of Pakistan’s economy and are crucial for the manufacturing sector in particular. As is the case with total financing in Pakistan, SMEs are also unable to allocate enough funds to investment since most of their loans go towards working capital. While 42% of loans go toward investments for small firms in the developing world, only 23% of SME financing in Pakistan goes toward the same.

Public money makes money

Someone important once said:

“While it is good that we see some public investment in utilities, a lot more needs to be done to bolster competitiveness. This should be done through direct investments in industry rather than subsidy provisions to inefficient sectors.”

Macro Pakistani

The connotation behind direct public investment is usually that the government takes a stake in the company. However, government investment in industry can take many forms.

To lower the risk profile of small firms, for example, instead of startups promising banks collateral such as land, government can guarantee some portion of the loan themselves. Basically, if the startup does not do well, the government will foot the bill rather than the bank seizing the startup’s land. Pakistan introduced a Credit Guarantee Scheme in 2010 but that has failed to take off. The primary reason, as the State Bank of Pakistan themselves identified, was inadequate marketing.

Regardless of government guarantees, small firms will be required to provide some sort of security to banks to encourage lending. The current government program guarantees 60% of a collateral free loan which leaves 40% uncovered. For context, the current regulation encourages collateral free loans or clean lending, of up to PKR 5 million for SMEs. But still, if an SME has to provide collateral, they might not have land to give to banks. Till 2020, banks required immovable property as collateral, which could be land or a factory or the machinery inside the factory. But recently, the Securities and Exchange Commission of Pakistan launched a Secured Transactions Registry. This will help SMEs provide collateral such as money owed to them by other people. So in case they default, the bank will have claim to the money they were going to get from someone else.

Data is King

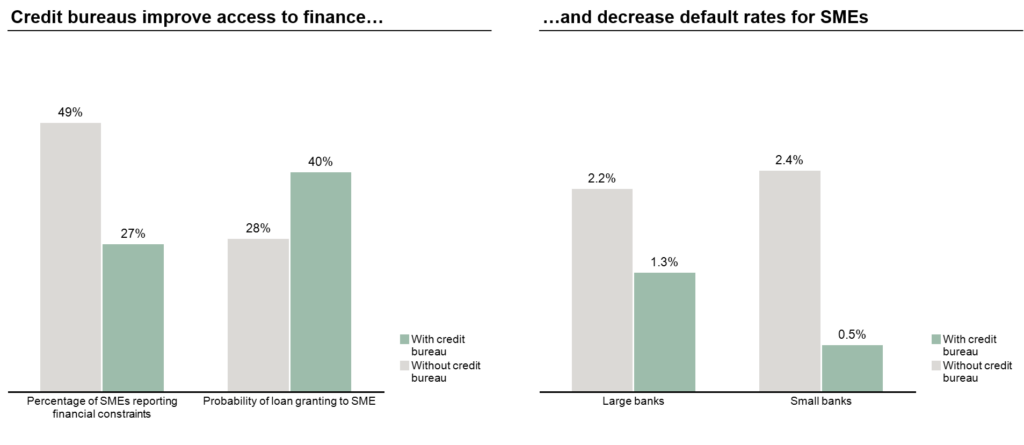

Since banks use complex risk calculations to determine if the startup will default or not, they need data to make that decision. Something like a private SME credit bureau would help banks make better informed decisions.

Global Impact of Credit Bureaus on SME Financing

Credit bureaus have improved access to finance and decreased default rates by SMEs in other countries and Pakistan should also look to do the same. I said private SME credit bureau because we have seen time and time again in this country that the public sector will be a slow-moving giant. We actually do have an Electronic Credit Information Bureau that bankers glance at before making loans today but it is not very useful. To improve financing in Pakistan, the government should work toward encouraging the entire financial ecosystem to become more lean, user-centric and allow data to be used in more effective ways.This will encourage investment, productivity and eventually employment in Pakistan.

I would think, in the COVID world, the lower credit-GDP ratio is a blessing, not a curse.

Suppose a bank recovers loans with 80% probability from a business (20% chance of zero return) and further suppose that the bank has made lots of similarly risky loans. In expectation, the bank is getting 80% of its loans back *in normal times*. During COVID, there is a high chance of synchronized defaults that would put the banking sector in great trouble (rise of non-performing loans). The higher the credit, the bigger the trouble there would be.

Let me know what Macro Pakistani thinks of this.

Yes but would need to define what the bar for low credit-GDP is. COVID-19 is obviously an exceptional circumstance. Historically, NPLs in Pakistan have been below 10% last I checked. Chances for synchronized defaults have increased during the pandemic but that’s what risk sharing facilities with the government/Central Bank are for. Given you are at less than 20% private credit to GDP, chances of a credit bubble bursting seem limited.