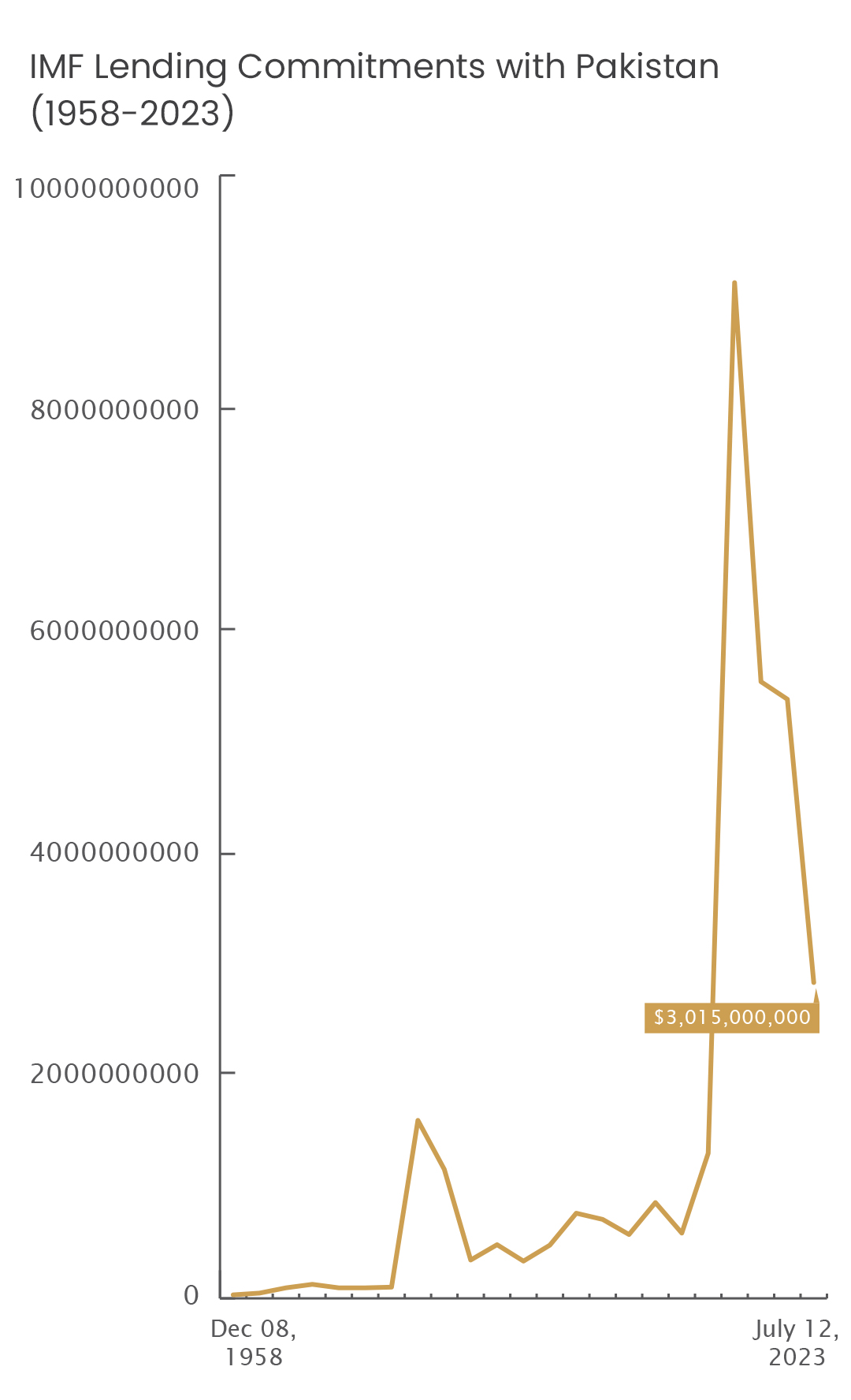

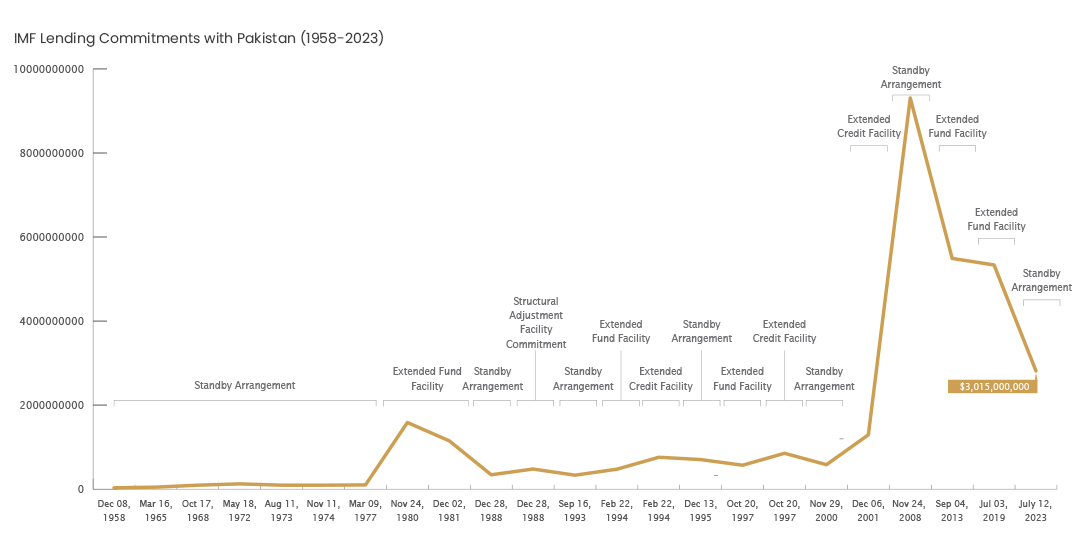

Pakistan’s most recent IMF bailout marks the 23rd time the country has went to the IMF for a lending commitment. Does this agreement hold the promise of stabilization, or will it be just another throwaway lending commitment in its long running history?

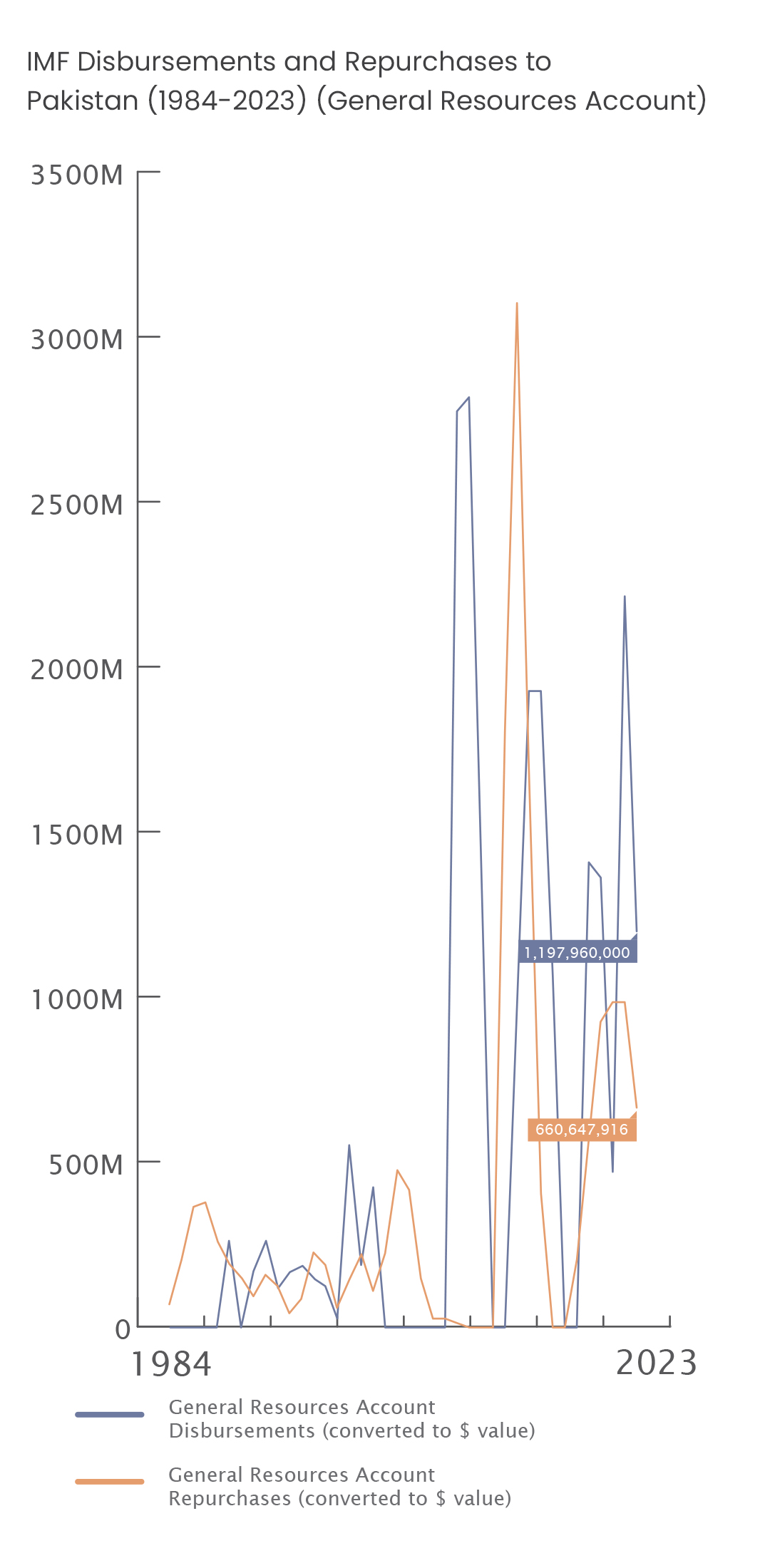

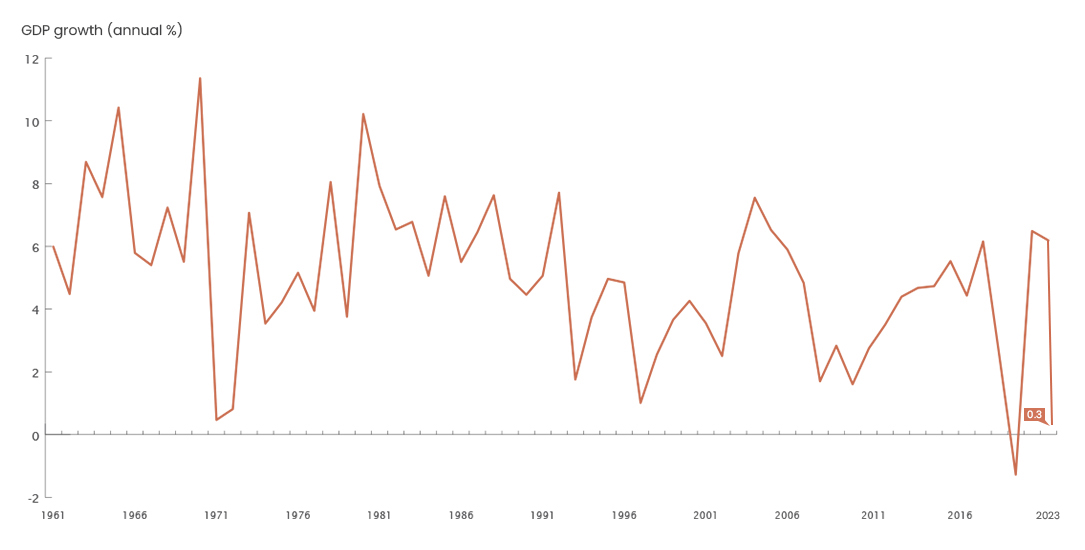

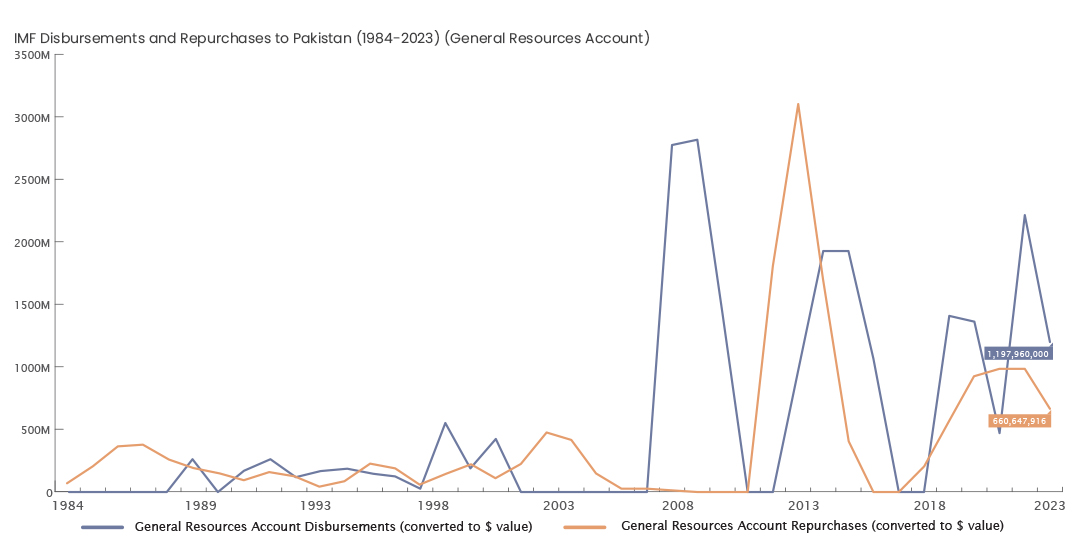

Pakistan recently agreed to another IMF stand-by arrangement worth $3 billion, with $1.2 billion having been paid upfront and the remaining $1.2 billion to be disbursed over the 9 month duration of the arrangement. Going to the IMF has become an almost routine occurrence in Pakistan with the gap between visits having shrunk considerably over the years. Between 1958-1988 11 lending commitments with the IMF were agreed to whereas between 1993-2001, 8 lending commitments were agreed to in less than one-third of the preceding time-frame. An interesting bit of trivia here, between 1958-1988, Pakistan’s GDP was on an unprecedented rise, being the highest among South Asian countries for almost the entirety of the 3 decades. Beyond that, between the 1990s and 2020s, it has hardly ever come close to recapturing that trend. While it may seem tempting to consider the preceding decades as the golden years, decline rarely ever comes immediately. The seeds of decline are often sown during a nation’s time to shine, hiding in the dazzling splendour of apparent economic growth and development. Germinating until the light is snuffed out.

Note: Value in USD

Source: IMF

The IMF as an institution:

It is important to first understand what the IMF is at its core. After the devastating impact of World War II, the IMF was established as a lender since many monetary institutions had become disfunctional. World leaders gathered in the United States of America in a conference held in New Hampshire between July 1st – July 22nd, 1994. Two institutions were created as a result of this conference, The World Bank and The IMF to ensure global monetary and financial stability.

The IMF’s role is largely to maintain a fixed exchange rate centered around the US dollar, British pound, gold etc. It aslo serves as a consultant for economic hardship, providing short term financial assistance and attempting to improve world trade ties.

Important to note is that when the IMF prescribes a policy revision, they believe that the issue largely stems from aggregate demand surpassing aggregate supply and as such centers most of its efforts around that, believing that by applying various tools and policies to curtail aggregate demand, the balance of payments issue can be resolved.

The IMF’s policy prescriptions for countries looking for advice is largely centered around 3 cases:

- Flexible exchange rate

- Tight monetary policy

- Tight fiscal policy

A flexible exchange rate begets devaluation, for the purpose of improving net exports (a component of aggregate demand) by reducing imports and increasing exports as exports become cheaper in the international market. However, on account of more expensive imports, inflationary pressure stacks. To offset this, the central bank resorts to a tighter monetary policy by reducing discount rates which leads to higher interest rates and lower returns on “investment” (another component of aggregate demand).

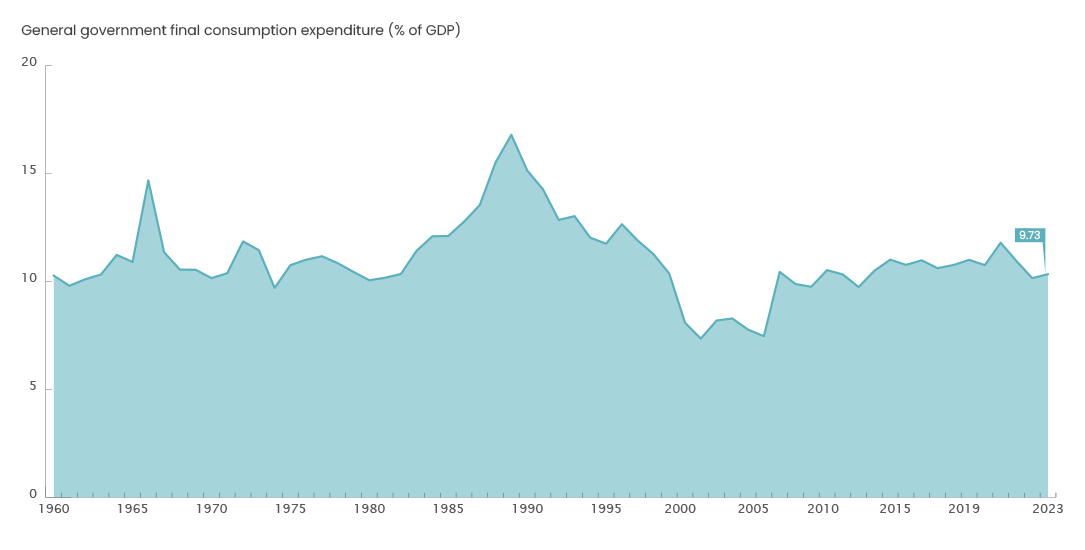

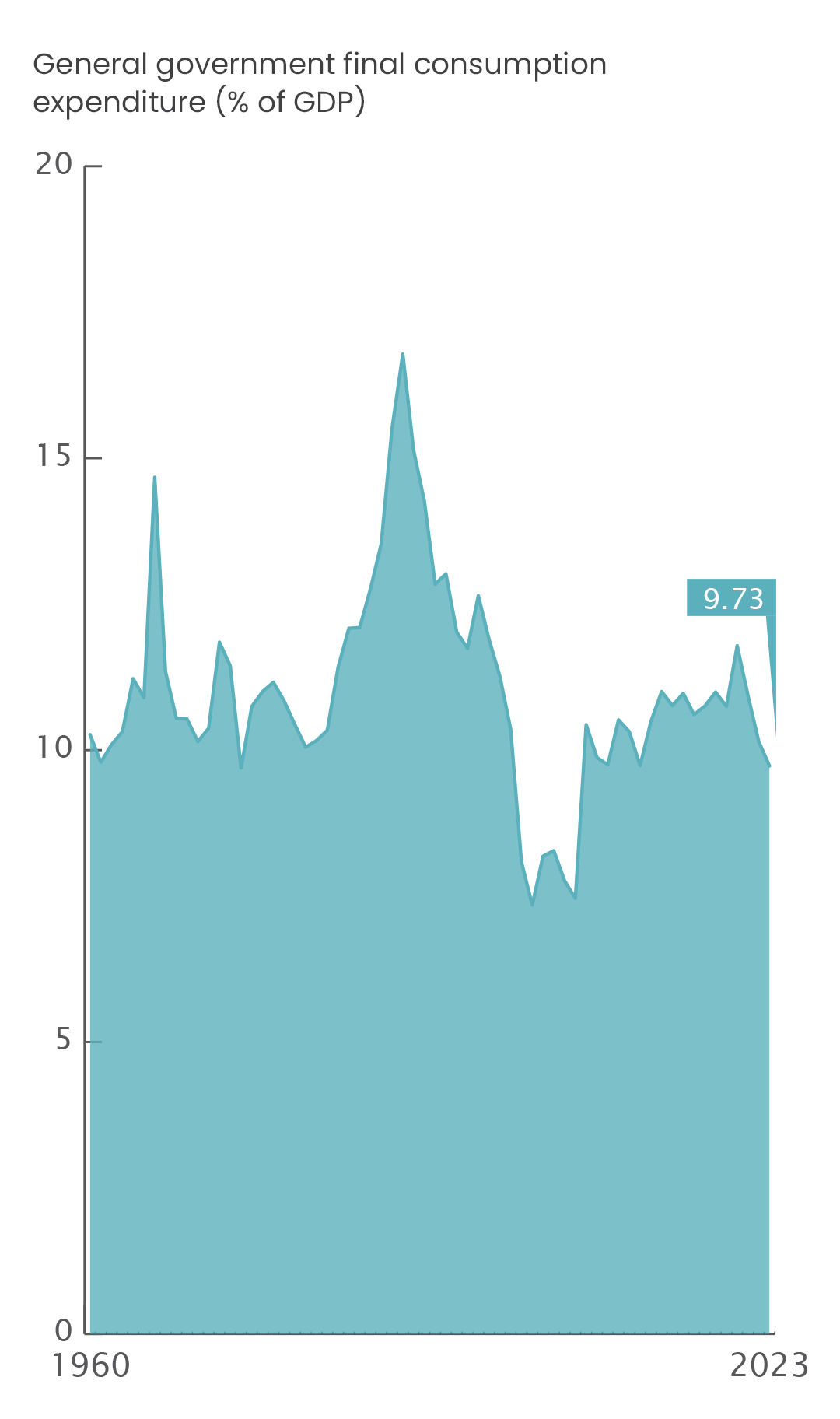

Meanwhile a tight fiscal policy means a reduction in government spending, (another component of aggregate demand). While most aspects of government are relatively rigid such as defence spending, payments, administrative costs etc. the government then curbs spending in the area with the most flexibility in spending, i.e “Development spending”, which in turn cuts public sector investment.

In summary, higher interest reduces private investment, while reduced development expenditure cuts public investment leading to an overall reduction in the GDP, which in turn slows revenue generation and job creation in the county. The details are layered but in the end the rising total expenditure over time coupled with reduced revenue generation causes mounting public debt and the government must borrow in order to offset the ever increasing budget deficit, falling into a debt trap and being forced to follow the IMF’s policy prescriptions on a quarterly basis, essentially handing over macroeconomic initiatives to another organization rather than domestic policymakers.

Pakistan’s Historical dealings with the IMF

To truly understand the core of the dilemma the country faces, peering into different time periods of Pakistan’s history could shed some necessary insights. For a visual breakdown:

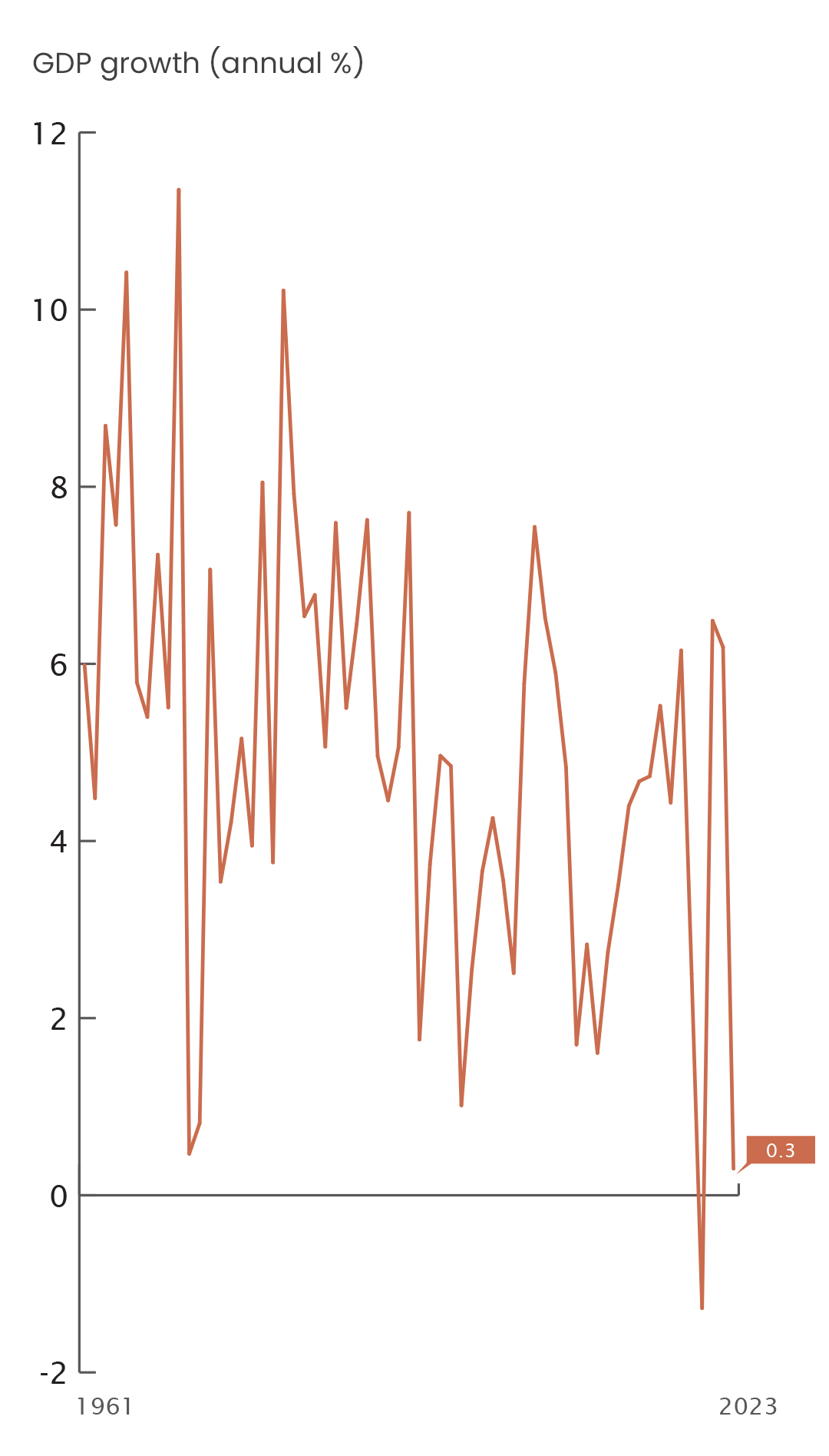

GDP is among the important indicators of economic well-being. Sharp ups and downs are reflective of relative instability while sharp drops in between various years indicate reduced income and consumption, which leads to various other issues such as labor force reduction to cut costs. Availing IMF funding in order to improve these various indicators tends to have the opposite effect in the case of Pakistan.

For personal convenience, we can break down the various lending agreements into 4 separate time periods:

- 1960-1988

- 1988-1999

- 2000-2013

- 2013-2023

1960-1988:

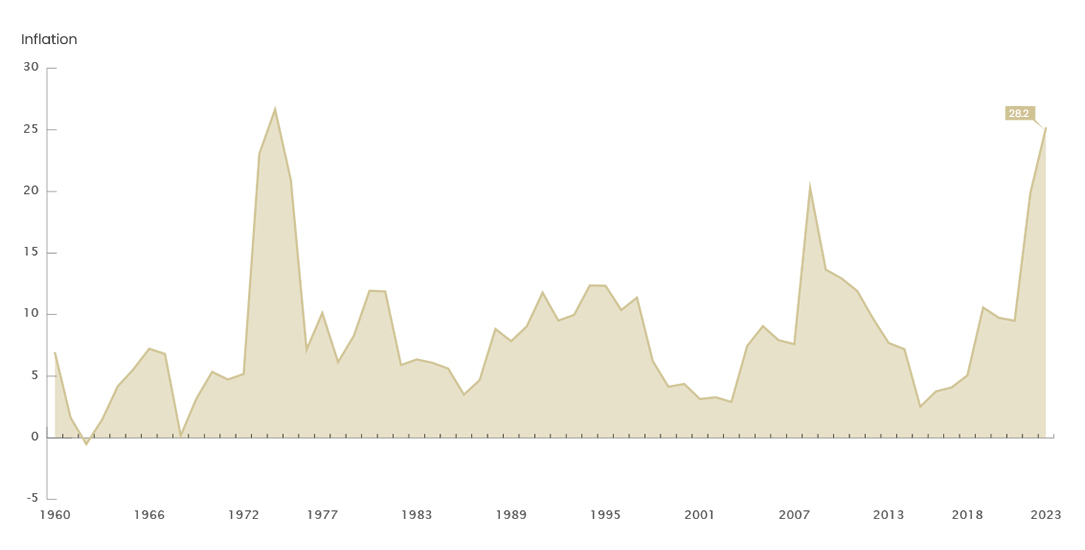

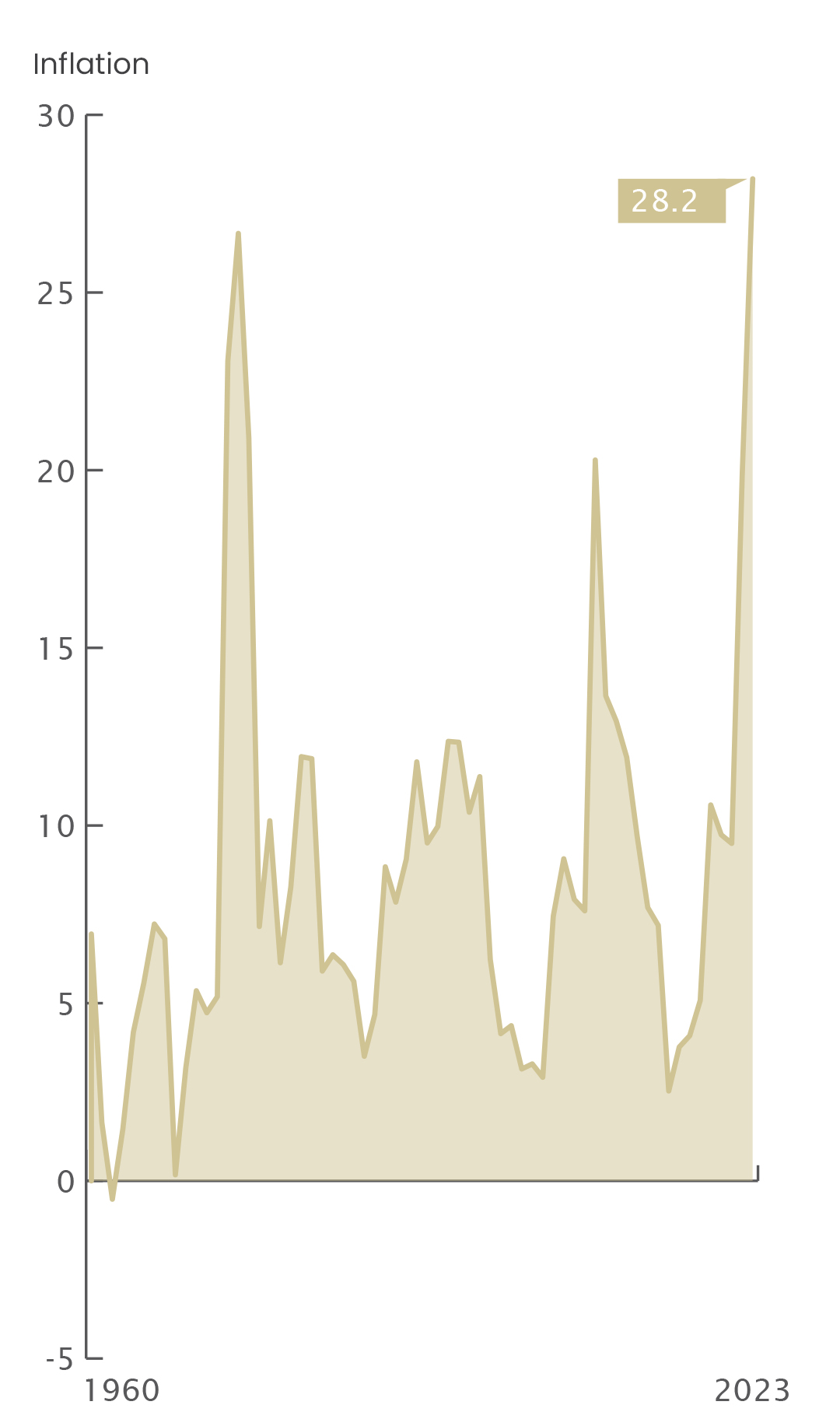

It is interesting to note that most IMF funding is usually availed during periods of intense political strife. The period of 1960-1988 was an interesting time for the country. Despite having only recently been granted independence, an impressive average GDP growth rate of 6.8% over the 1960s was maintained. That being said many external issues would throw a wrench in productive undertakings and political complications would cause many undue issues. Nowhere is this more apparent than the seperation of East and West Pakistan in 1971, reflected by the fall in GDP growth rate down to 0.5%. Shortly after, Butto’s nationalisation scheme would also be implemented, which slowed down economic growth due to complications in effective implementation resulting in staff mismanagement, increased investment costs and decline in service quality withing state owned enterprises, while also reducing the private sector’s incentive to invest. Couple this with the blowback from productivity losses and balance of payment issues arising due to East Pakistan’s separation and the global recession in 1973, it comes as no surprise that IMF funding was sought for 3 consecutive years between 1972-1974 inevitably contributing to a sharp spike in inflation rate for the following years, reaching a record high at 26.2% in 1974.

It is interesting to note that most IMF funding is usually availed during periods of intense political strife. A persistent supporting issue that makes IMF funding largely inefficient since time immemorial, is the extreme difference in vision between leaders with little to no follow-up on each other’s plans. Once one’s tenure ended, most projects / budget plans of the old regime tend to be sidelined to give priority to a new one by the next regime, or completely different goal posts are set which sometimes undo any progress made by the previous regime, a trend that continues even today.

The 1980s saw the advent of the Soviet-Afghan war. With Pakistan and Afghanistan as major players in the region to oppose the Soviet march, many foreign powers, including America, provided funding to Pakistan and by extension, Afghanistan, to act as a proxy on the front lines and repel the invasion to deny Russia a strategic geographical gain. This unprecedented exogenous inflow of revenue was capitalized on greatly. Couple this with steps taken towards a new deregulation policy, increased remittance inflow and other factors, helps explain how inflationary pressures remained low throughout the 1980s despite two IMF loans taken in 1980 and 1981. Pakistan utilized the incoming revenue to bolster its defence budget and improve its economic strength, reflected in how government spending was on an increasing trajectory and GDP reached an average of 6.5% over the decade.

Some interesting tidbits on the various impacts of some of the events of these years can be viewed in this data story.

1988-1999:

In the years following the end of the Soviet-Afghan war, government control of Pakistan would rotate between the Pakistan People’s Party and Pakistan Muslim League (N). A time of economic decline was observed as the flow of foreign funding came to a halt and security risks in the country increased exponentially owing to the rise of Klashnikov culture and mass immigration towards Pakistan.

While the two governments took steps towards further privatization and liberalisation in the country, unstable political climate as well as opposition by public sector entities and worker unions led to significant delays in the implementation. Moreover, public debt and unemployment, along with fiscal and external debt were on the rise, leading to seeking more IMF loans in hopes of implementing policies to improve stability, though the endeavor would be largely unsuccessful. Things would come to a head in 1998, when the first public nuclear tests led to then PM Nawaz Sharif declaring a state of emergency which put a halt to the remainder of the privatization program, while also shutting down stock exchange. The tests would also lead to numerous trade sanctions / embargos on Pakistan. With foreign exchange reserves only worth $400 million still in access, access to foreign markets restricted due to decreased credit rating, it helps to paint a picture of why average GDP growth over the decade hovered around barely 4% and poverty rose exponentially.

2000-2013:

Following up on the issues of the previous government, two IMF loans were taken on 2000 and 2001 as a stimulus to begin course correction. The main goal was to resolve the mounting debt crisis in the country and improve poverty and unemployment ratios. While there was substantial improvement on these economic indicators and GDP grew at a respectable average rate of 6.3%, the improvements were not sustainable as by the end of Pervez Musharaff’s tenure, Fiscal and current account deficits widened, leading the country once again to borrow excessively, which led to a spike in inflationary pressure and money supply, stifled foreign capital inflow and weakening exchange rate as foreign reserves began depleting again. With how the economy was weakening towards the end, the next government under Asif Ali Zardari had to seek out an IMF loan again on 2008, as soon as they came to office.

The years between 2008 and 2013 were troubling times for Pakistan with unsustainable economic policies pushed at the forefront, amid increasing cases of rampant corruption in all institutions. There were severe coordination issues between the fiscal and monetary authorities as well, leading to a persistently high case of inflation, unemployment, energy shortages etc. when comparing GDP growth and inflation to the previous tenure, both worsened from 5.1% and 5.7% to 2.8% and 12.7% respectively.

2013-2023:

Enter the last decade and Pakistan’s economic sphere is no closer to a stable outlook than any time period before it. The persistent failure of the people in power to provide adequate reforms and instead falling back to the IMF when inconveniences occur has led to mounting outstanding repayment debt, stifling economic growth as Pakistan remains one step away from being ranked as a defaulting country by credit rating agencies.

In this past decade alone, the three greatest IMF loan payments were taken.

Overcoming the hurdles:

The main issue with the IMF’s policy prescription in terms of Pakistan is that the IMF fails to account for the fact that the root of Pakistan’s balance of payment issues stems from self-induced shocks rather than exogenous ones. Despite having completed 3 of 4 IMF programs between 2001 and 2019 with comparatively little delays compared to the years prior, Pakistan has had to once again go back to the IMF. It begs the thought that perhaps there is an underlying issue in the economy that remains untreated and that the areas the IMF programs focus on to achieve ‘stability’ benchmarks may be fundamentally off the mark hence why the country finds itself at IMF’s front door so frequently. When taking into account the period between 2008-2018, IMF policies implemented in pursuit of stability led to a slowdown of average GDP growth to 3.8%, rising external debt and unemployment, and overall poverty.

Of course, that’s not to say the country itself is free of blame. Pakistan has had no shortage of macroeconomic issues since its inception. While exogenous factors such as the 2022 floods have added to the list of woes, it cannot be denied that the country tends to teeter on self-sabotage on various economic fronts even in the absence of such variables, whether it be an unsustainable trade policy, persistent energy crisis, rising circular debt, etc. Many institutions are not performing adequately even in the absence of exogenous shocks. Taking a bailout package before addressing the root causes of all these inadequacies simply provides the country with temporary relief before inevitably leading us back to the IMF. whose policy benchmarks act more as roadblocks that put the country in a deeper debt trap.

Though the prospects of change are difficult, the numerous issues plaguing the macroeconomic aspects of the country offer an equal amount of opportunity for improvement. There needs to be a set of broad policy reforms that can target key problem areas of the economy to circumvent the persistent dent in the economy’s operation.

Inefficiencies to Target

Power sector subsidy reforms are an inherent issue that need to be looked into. As it is, the cash flow of the power sector remains a problematic anomaly that consistently adds to the fiscal debt and overall costs to businesses and individuals. Taking measures to reassess where inefficiencies occur in the sector and how much leniency is given to them could be a major milestone in tackling and resolving the dent in productivity and the funding that occurs here.

Tackling weak links of fiscal policy i.e. tax collection and broadening the tax base. Implementation of strong follow-ups to fiscal policies has always been an area of struggle for the economy. The shadow economy and financial grey areas which lead to incomplete/inaccurate financial reports need to be tackled. Furthermore, a monumental push toward registering and holding relevant tax-paying citizens accountable requires the utmost attention.

Change in spending priorities / forward-looking fiscal and macroeconomic policies. Shortsighted economic policy is an issue, as well as policy that is too focused on a specific area. Pakistan’s programs under the IMF have sought to take any measure to reduce the budget deficit with little success. Focusing on more balanced macroeconomic policies with due credence given to significant developmental policy is important.

Conclusion

The latest IMF loan agreement, sadly, does not come as a surprise. Authorities continue to stall and repeat the same course of action that has not alleviated Pakistan’s budget deficit in any meaningful way. High inflationary pressure and interest rates make any government initiative difficult to successfully complete while fiscal and external debt continues to worsen. Amid such a troubling climate and limited resources, it is doubtful if the current IMF program will be successfully completed.

Regardless, in order for things to improve, a greater push towards reduction of imports, promotion of exports, remittances, and increased incentive towards foreign direct investment ought to be focused on and many structural reforms will need to be introduced for such things to become a reality. Many opportunities for growth and many initiatives such as CPEC are yet to be fully capitalized on, so a simple reassessment of development priorities can still have quite a noticeable change on the trajectory of the economy.