On the face of it, lack of housing does not seem to be a problem in Pakistan. Switch on the TV and you are likely to see Park View City advertising free plots of land in the Pakistan Super League. Go for a drive down the Lahore-Islamabad Motorway and there are housing projects at virtually each step—from an 18-hole golf course in Capital Smart City, to a blue mosque in Blue World City (obviously). How then does this square up with the housing shortage in Pakistan, which is estimated to be 10 million homes? The answer lies in Pakistan’s vastly unequal housing market.

Housing for the rich, not the poor

According to architect and urban planner Arif Hasan, in 1991 the cost of making a semi-pucca house in Karachi was 8 times the daily wage of an unskilled worker, whereas by 2008 this figure had risen to 60, a more than seven-fold increase. More recent data on housing prices similarly indicates that the bottom 60% of income earners disproportionately suffer from higher rates of housing inflation. It is unsurprising then that nearly half of Pakistan’s urban population live in slums, or katchi-abadis, where many homes suffer from structural deficiencies, and lack of access to sanitation and utilities.

Unfortunately, this is only likely to get worse. 700,000 new housing units are needed just to keep pace with population growth each year, but only about half that number is being added to the housing supply on a yearly basis. When one factors in the 200,000 housing units that become obsolete each year, the situation appears even more dire.

So how exactly did we end up in a situation where the most likely way to own a plot of land is correctly guessing cricket trivia in the PSL? Well, it’s complicated (not the answer to the trivia question by the way, which is Islamabad United’s 97/0 vs Quetta).

The prohibitive cost of housing

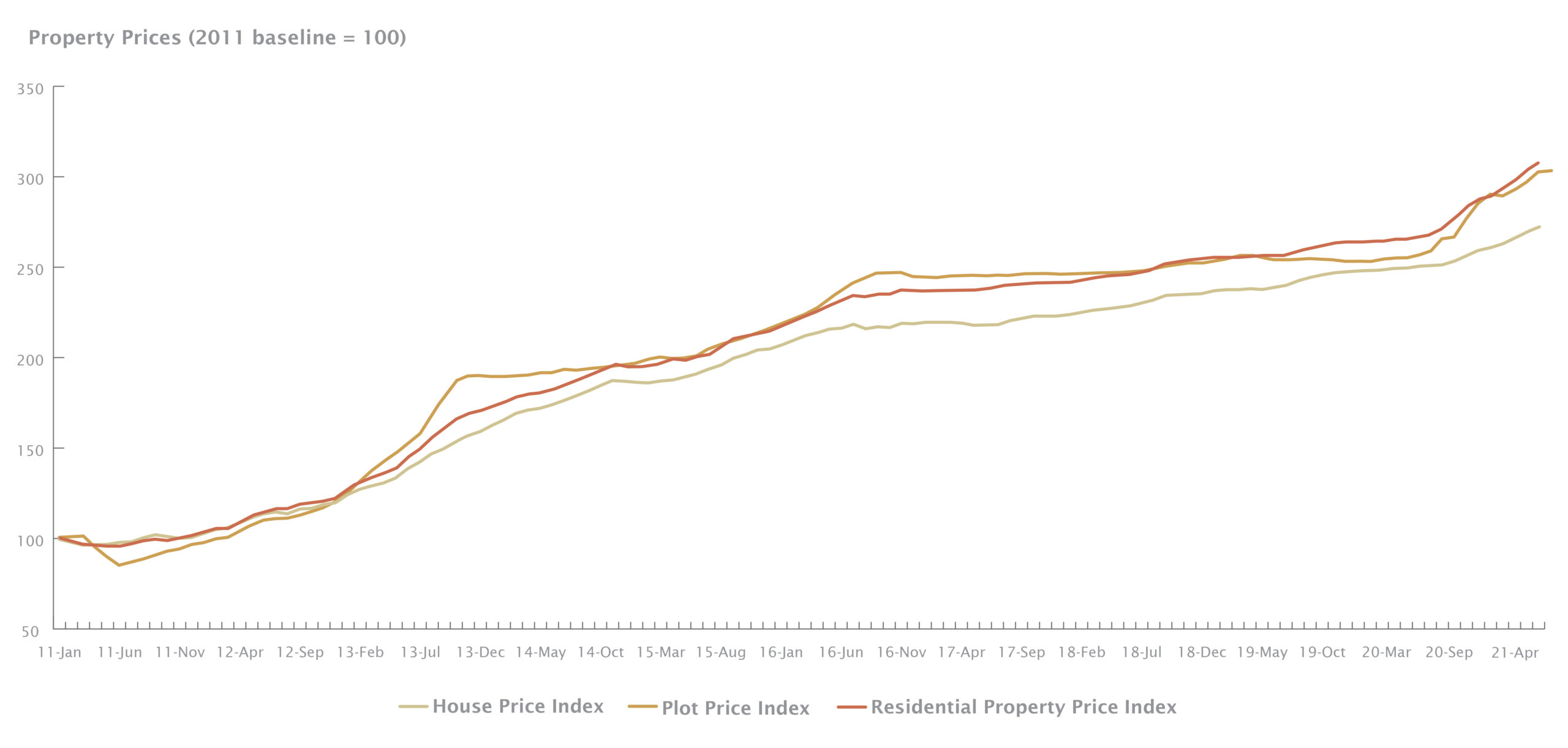

Perhaps the single biggest challenge that faces most people trying to own a home is high prices, a theme that remains stubbornly relevant in Pakistan. Estimates vary, but data from Zameen.com (which admittedly does skew towards urban and affluent areas) shows that, the per square feet prices of both plots as well as housing units have trebled since 2011.

Prices of plots and housing units in Pakistan have almost trebled since 2011

Source: Zameen.com; MP Analysis

Source: Zameen.com; MP Analysis

These high prices are partly due to the large increase in population, relative to the levels of housing stock available. Between 1981-1998, housing units in the country increased by 18%, whereas the population increase in that time was 57%. Overpopulation alone isn’t the problem however—our enthusiasm for large families is perhaps only rivalled by our enthusiasm for investing in real estate. An analysis of residential real estate holdings in Pakistan concluded that we invest roughly twice as much in real estate as Americans do in their country (3.3% of the GDP compared to 1.6% in the US). According to that same analysis, even if one leaves aside plots and looks purely at constructed residential real estate, overinvestment has still led to prices being overvalued by nearly 70%.

Mortgages? We don’t do that here

Another crucial component to the housing unaffordability crisis is the mortgage crisis (we only deal in crises in Pakistan). Around the world, vast numbers of people are able to buy homes by getting a mortgage from the bank. Right next door, India has a mortgage to GDP ratio of 10%; South Asia overall has a ratio of 3.4%. Meanwhile in Pakistan, that ratio stands at…0.27%.

The causes behind our stunted mortgage market are varied. The lack of “clean titles” i.e., contestation over who really owns a property due to few computerised land records, is one reason. Our foreclosure law has been another stumbling block. Until a recent change in its interpretation, banks could not seize property from a mortgage defaulter without first going through a painfully slow process in the banking court (the delays endemic to our judiciary are worth another entire article). That change has now been upheld by the Supreme Court.

Cheaper housing is a necessity

Perhaps the simplest reason why more mortgages aren’t extended in Pakistan however is that, quite frankly, people can’t afford them. According to the Pakistan Bureau of Statistics (PBS), the median urban Pakistani household’s monthly income is 34,000 rupees. Meanwhile, the price of an average urban house or apartment is about 12 million rupees. If we assume some undercount in PBS numbers due to methodology and survey date (2018-19) and optimistically round up the average monthly income to 50,000 rupees, that still makes an apartment more than 18 times the average annual income, even though purchasing a house should not ideally cost more than four times one’s average annual income. In that income bracket, that translates to finding an apartment in the city for about 2.5 million rupees—good luck.

This is why even HBFCL, a government entity that is supposed to give loans for affordable housing, lends to those making between 70,000 and 100,000 rupees a month—a number that places those households firmly in the top income brackets of the country. The solution to affordable housing then quite clearly needs to involve some form of subsidised or free accommodation. In fact, just to stem the growth of katchi abadis alone, Pakistan needs 200,000 low-cost housing units each year. Can the Naya Pakistan Housing Program be the answer?

Imran Khan to the rescue?

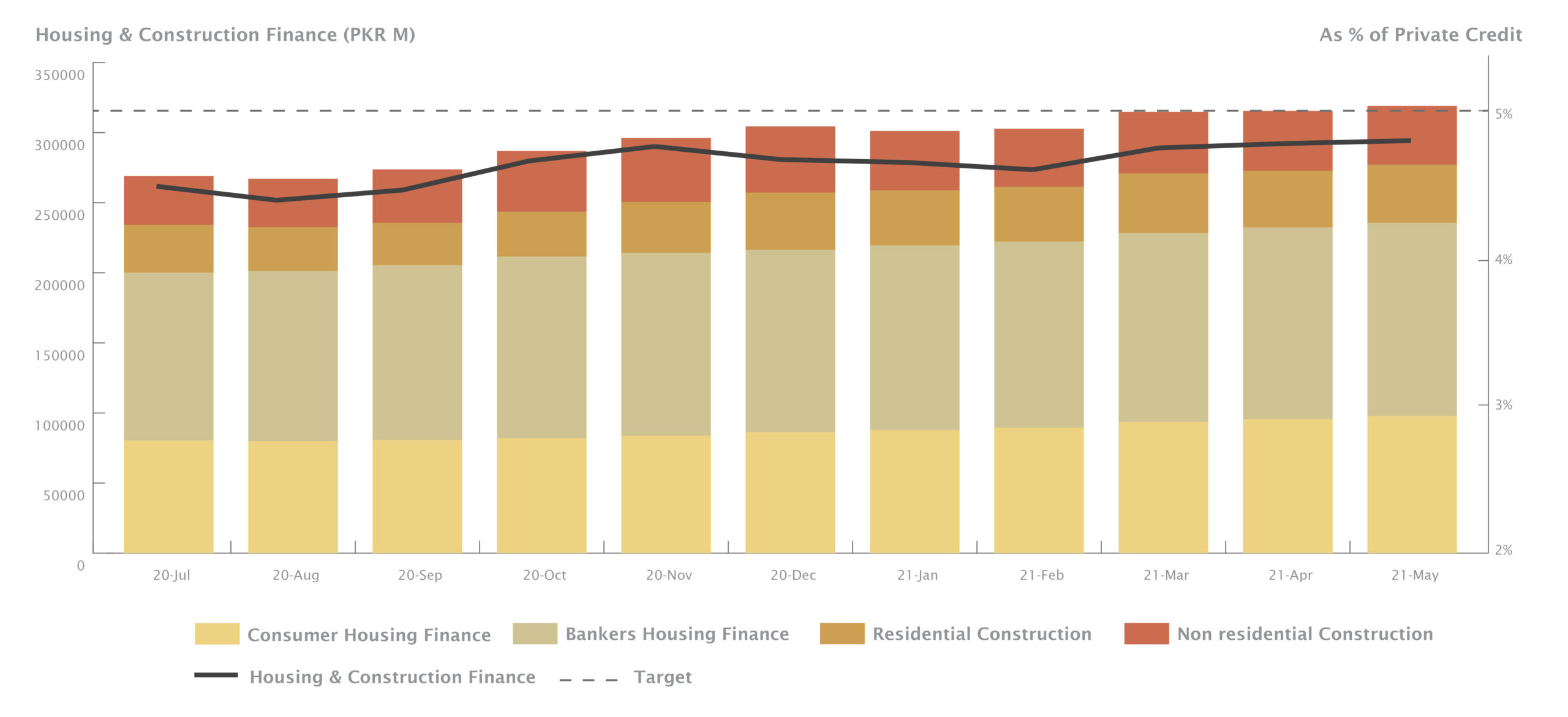

With the aim of building five million new homes in five years, Imran Khan has set himself an ambitious target. And to be fair to him, he has at least taken some steps to move the needle on affordable housing. The change in the interpretation of the foreclosure law came about as a result of the Prime Minister appealing to the Lahore High Court’s Chief Justice to take on the case. Pressure was exerted on the State Bank of Pakistan (SBP) as well to do more on housing finance, resulting in a SBP notification for banks to increase their lending for housing and construction to 5% of their private sector credit by December 2021. His government also finally set up the Pakistan Mortgage Refinance Company (PMRC) which will give banks long-term funding to promote housing finance.

Then there is the Naya Pakistan Housing Program. A primarily developer-led model, the scheme on the one hand aims to subsidise land for property developers to build more housing, including fixed percentages of low-cost housing. On the other hand, it also plans to give first-time homeowners a 36-billion-rupee subsidy over time to be able to buy plots or homes in these projects at prices ranging between two to four million rupees – aiming squarely at those earning around or above average income in the country. Successful applicants would have to pay 10% of the home’s value up front and then pay the rest over 20 years in monthly instalments of around 20,000 rupees each after they receive ownership of the home.

From theory to reality

In theory, a lot of these proposals sound promising. The reality, inevitably, is a little different. Firstly, PMRC only plans to refinance 5000 mortgage loans of 3 million or under by 2023. Second, the SBP notification may actually disincentivise banks from growing their overall loan portfolio—as 5% would have to be devoted to housing credit—preferring instead to place their funds in safe, lucrative government securities. Meanwhile, as far as meeting the SBP target is concerned, lending figures from the SBP in May 2021 tell us that, excluding bank employees, lending for housing and construction was 2.7% of domestic private sector credit. Including bank employees, that figure was 4.8%—which separately tells us the ridiculous statistic that the value of bank employee housing loans is greater than both lending to the construction sector, as well as housing loans for the 199 million Pakistanis who are not bank employees.

Banks meet SBP’s housing target by disproportionately lending to own employees

Source: State Bank of Pakistan; MP Analysis

Note: Excludes financing/investment to Real Estate Investment Trusts (REITs) and Pakistan Mortgage Refinance Company (PMRC)

There are several issues with the Naya Pakistan Housing Program too. Firstly, only housing units that have been completed in the past one year are eligible for financing under this scheme, which rules out most buildings in the country. Another major concern is the format of the program. If selected successfully in the ballot, a family would have to pay 150,000-400,000 rupees up front, even though they are not likely to be able to live in a fully constructed home for another two years. There are many families that could afford to pay the 20,000-rupee monthly instalments as they are already paying similar amounts for rent. But the number of families that can afford to pay more than 200,000 rupees up front for the promise of a liveable home in two years’ time is much fewer, especially considering that Pakistan has one of the lowest savings rates in the world.

Changing governments, same policies?

Despite these concerns, if successful, the Naya Pakistan Housing Program could still have a major impact on the availability of housing in the country. The question however is if it will be able to deliver on its lofty aims. Building five million homes in five years is akin to winning the Cricket World Cup despite losing the first three games. And yes, Imran Khan managed to pull that off in ’92. But this time, instead of trying to win the thing, he’s offering incentives to private third parties like Falaknaz Builders in the hope that they can win the cup for him instead.

The developer-led model of construction has been tried by various governments in Pakistan’s history. Nawaz Sharif announced the Apna Ghar Housing Scheme in 2013 that planned on building 500,000 homes in five years through a similar public-private partnership model. It didn’t really lead to much. The PPP government too announced ambitious plans in 2008 to build low-cost housing all over Sindh through the Shaheed Benazir Bhutto Housing Cell. It didn’t really materialise either. Meanwhile, Imran Khan’s promise requires a million homes to be built annually, but three years into his government, even the most optimistic reading of the unofficial data suggests that work is underway on less than 100,000 housing units nationwide. Not a single project under Naya Pakistan Housing Program is yet to be completed. If the PTI government wants to genuinely deliver on its ambitious promises, it will have to do much more than its currently modest steps.