Climate Change in 2020

Climate change is going to define the Twenties. The conversation around this topic has begun to reach a crescendo, so much so that even the 2020 US Election has been called the “Climate Election”. The fact that global warming is an existential threat is not exaggeration, but humanity is responding. Major global powers have pledged to become ‘carbon neutral’ by 2050 (+-10 years), including Japan, the European Union, China and even Amazon. ‘Carbon neutrality’ simply means we do not displace further carbon from the ground, into the atmosphere, to avoid catastrophic temperature increases. So what is everyone trying to achieve with this? Why is this an issue?

From 1820 to 2020, the average temperature of the planet has increased (on average) by 1 °C. This increase is accelerating, causing erratic weather patterns, including floods, hurricanes, wildfires and heat waves. For every 0.5 degree centigrade increase, the likelihood of extreme weather events substantially increases, which is why a cumulative increase of 1.5 °C is the scenario that the global community is hoping to achieve – with a 2 °C increase being the maximum possible in order to continue living in conditions that bear some semblance to human history.

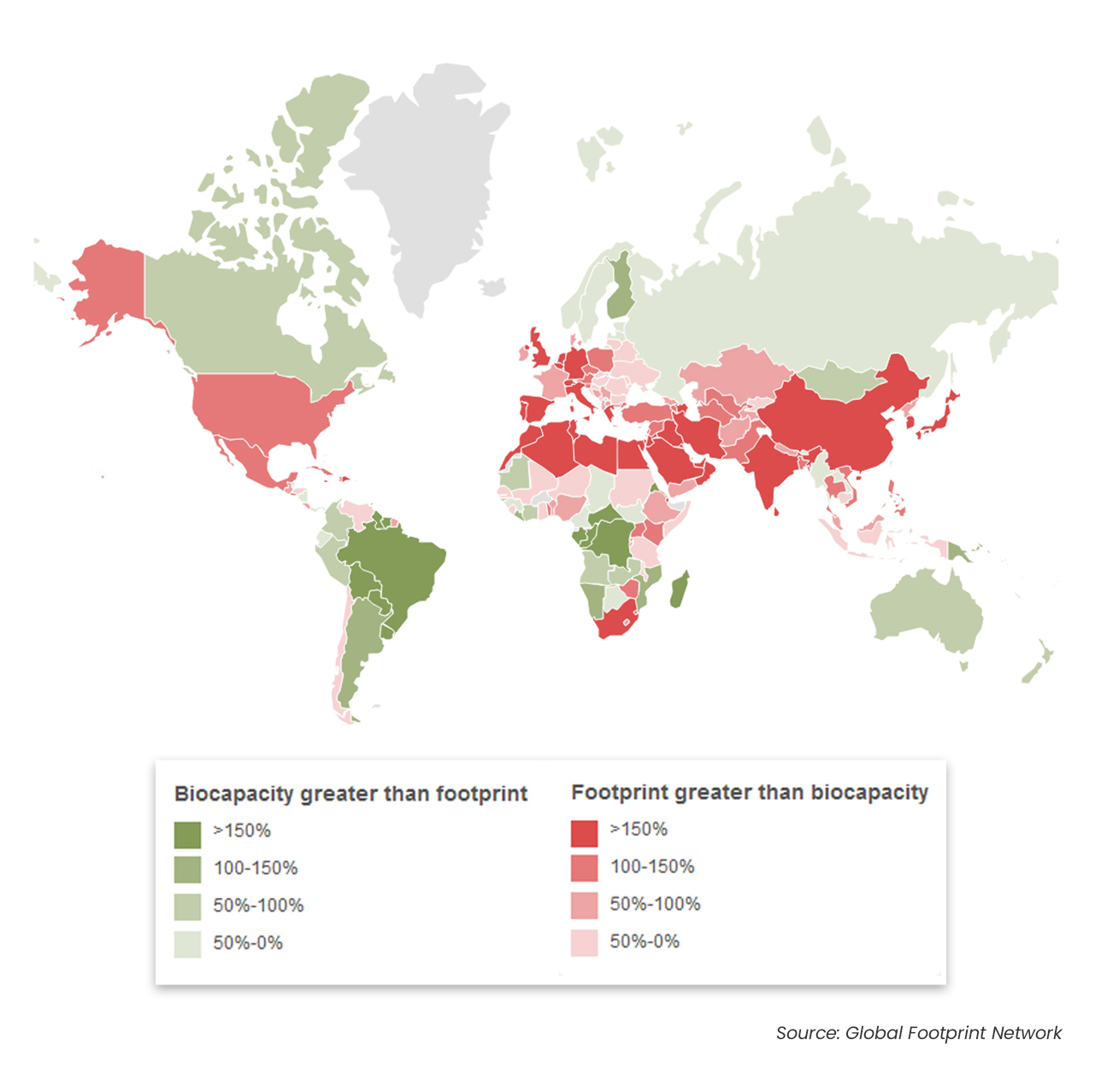

Humanity is consuming biological resources faster than the planet can replenish them. The world is in what is known as an ecological deficit. This occurs when the Ecological Footprint of a population exceeds the biocapacity of the area available to that population. A national ecological deficit means that the nation is importing biocapacity through trade, liquidating national ecological assets or emitting carbon dioxide waste into the atmosphere. An ecological reserve exists when the biocapacity of a region exceeds its population’s Ecological Footprint. Estimates claim that humanity is consuming about 170% more biological resources than our planet’s ecosystem can regenerate.

Country wise breakdown of ecological deficits/reserves

On average, the humanity is consuming 170% more biological resources than our planet’s ecosystem can regenerate.

Source: Global Footprint Network

Why should Pakistan care?

Pakistan’s Ecological Footprint exceeds its biocapacity by 129%. In 2016, our ‘budget’ was approximately 70 million global hectares (gha), while our ‘expenditure’ was roughly 161 million gha. This deficit has consistently grown at a worrying pace post the 1960s. Comparatively, ecological deficit for Afghanistan was at 70%, Bangladesh 108%, Vietnam 108%, India at 173%, Sri Lanka at 198% and China at 278%. The entire region is on a dangerous path of unchecked overconsumption, and without significant widespread change, there is very little light at the end of this tunnel.

Pakistan’s Ecological Footprint and Biocapacity

Pakistan’s ecological deficit has grown by 7% annually since 1960

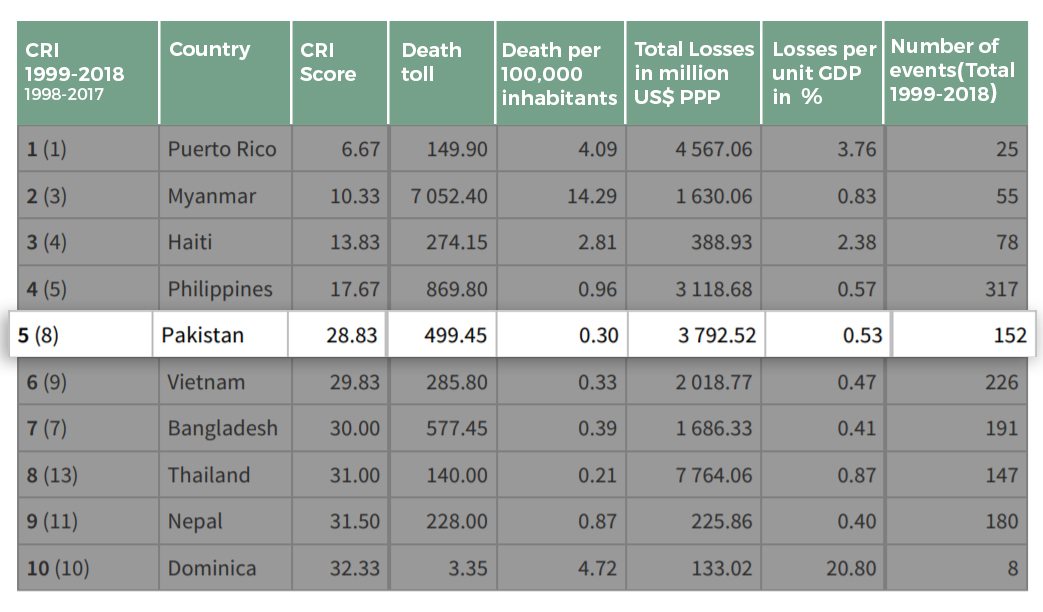

The Global Climate Risk Index (CRI) calculates how badly a country has been affected by weather related loses – the 2020 report shows escalating climate damage across the globe, with the poorest countries being the most impacted, as well as naturally having lower capacities to endure hardships, due to constrained resource availability. Pakistan is number five on the list of most affected countries between 1999 and 2018. This means that the country is one of the top five countries being impacted by climate related events. Indications are that this will continue to be the case going forward.

According to CRI data, Pakistan falls in the category of unfortunate countries that are “continuously affected by extreme events”. The data shows that Pakistan faced 152 such extreme events in the 20-year period under review, the magnitude of which was amplified and attributable to climate change. This led to an average of 500 casualties per year, totaling 10,000 lives lost, in addition to a loss equivalent to $3,792.52 million (PPP adjusted) as well as a collapse of per capita Gross Domestic Product of 0.53% per year. The PPP adjusted loss is equivalent to losing $190 million per year – for context, the budgeted federal expenditure for Environmental Protection in 2020-2021 is equivalent to roughly $3 million. What’s more worrying is that the budget allocation was reduced by 8% from last year.

Long-term Climate Risk Index (CRI)

Pakistan was ranked 5th amongst countries most affected from 1999 to 2018

Source: Climate Risk Index

Heatwaves and productivity loss

Abstract rankings on a list do not quite convey the full story though. Let’s look at heatwaves as an example of climate induced suffering and economic hardship. Pakistan has suffered multiple heat waves in the recent past, killing 1,300 people in 2015, 4 in 2017 and 65 in 2018. Death tolls are just the tip of the iceberg (this is a climate pun) with heatwaves though, documented to cause enormous economic costs. In 2017 alone, the world lost 153 billion hours of work, which means roughly half the global population not working for a week, because it was physically too hot to work. Most of these lost hours are accounted for by the agricultural sector, naturally being more labor intensive. Given Pakistan’s agrarian economy, this does not bode well, especially as Macro Pakistani has already discussed stagnant productivity in the agricultural sector.

By 2030, working hours to be lost in Pakistan due to heat stress will be equivalent to the country losing 4.6 million full time jobs. These losses will be concentrated in the agriculture and constriction sectors. Both sectors are priority areas for the current government and account for almost 22% of Pakistan’s GDP. While South Asia is generally expected to be hit hard by climate change, Pakistan is expected to hit worse than average across sectors.

Working hours lost to heat stress by sector (2030 projections)

Over 5% of total working hours will be lost due to heat stress in Pakistan

Heat stress also acts like an inequality multiplier, adversely affecting the less fortunate far greater than those with the resources to avoid the worst effects, both between nations as well as between populations within countries. Additionally, regions that have the lowest greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions are the worst affected by heat stress. According to the International Labour Organization, with GHG emissions of only 2.2 tonnes of carbon dioxide equivalent per capita, Southern Asia is the sub region with both the highest productivity loss and the lowest emissions per person.

It is increasingly becoming a contributing factor in families migrating from rural to urban areas and from hotter to cooler countries as well. The optimal average temperature for economic activity is around 13 degree centigrade, a sustained rise over this starts to drop economic productivity and the rate of decline continuously accelerates, with countries having a higher average starting temperature faring the worst.

Flooding and city loss

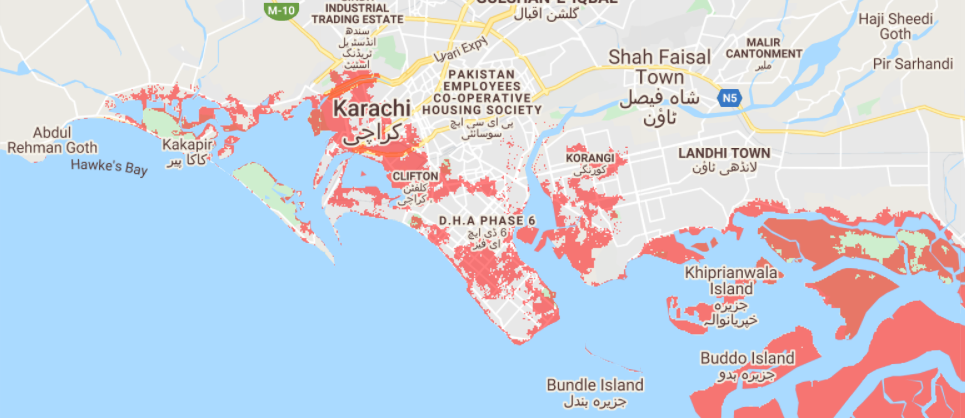

Perhaps the most tangible way to understand the damage changing climate patterns are causing is to look at the floods that Sindh experienced in August 2020. Karachi was also flooded in 2017, killing 23 and in 2009, killing 26. The floods in 2020 however, killed at least 40 people. This is particularly relevant because under climate projections, key areas of Karachi will be submerged by 2050. Expected rise is global sea level is almost 2 meters – currently, an estimated 230 million people worldwide live below 1 meter.

Land projected to be below 10-year flood level in Karachi by 2050

Even with moderate climate measures in place, key areas will be submerged by 2050

Source: Climate Central

If you’re curious, you can explore what Karachi looks like if sea levels rise further here. SITE and especially Korangi, two of the most economically vibrant locations in the country are projected to be underwater. This should not be hard to conceptualize, since the floods that brought Karachi to a complete standstill recently are still fresh in everyone’s memory. With businesses not able to operate, people not able to commute or leave their houses, we were given a grim look into what the future holds if the world continues down this path.

Failure to act today would mean practically losing Karachi. Losing its port infrastructure, displacing the only truly cosmopolitan city of Pakistan and very truly the economic hub of the country. This scenario would also see the purported $50 million investment into developing Bundal Island would literally be like throwing money into the Arabian sea – as that island is set to be completely submerged in a couple of decades.

It clearly makes sense then, for Pakistan to be hugely concerned about this situation. Is there any good news? Should we be panicking? Maybe something in between? We will explore the actions Pakistan has already taken and where we can push for more in the next article.

Great work explaining the concept in easy to understand words. The article was enlightening and terrifying at the same time. The picture becomes even more dramatic if you account for the fact that the rate of increase in biocapacity is expected to decrease in the coming decade, particularly for countries such as Pakistan that are going to be hit hard by climate change.

I will stay tuned for a follow-up article 🙂

Thanks Saad! That was what I was trying to accomplish with this article.

And yes, there are a lot of variables at play that weren’t explored, in the interest of keeping it concise – including diminishing biocapacity enhancement forecasts.

The bleak outlook is why we need to be having these conversations now – share the article with a few friends and let’s build the conversation. The next article should be out soon as well 🙂

Hi Saad, the second article is up 🙂