Climate Action & Pakistan

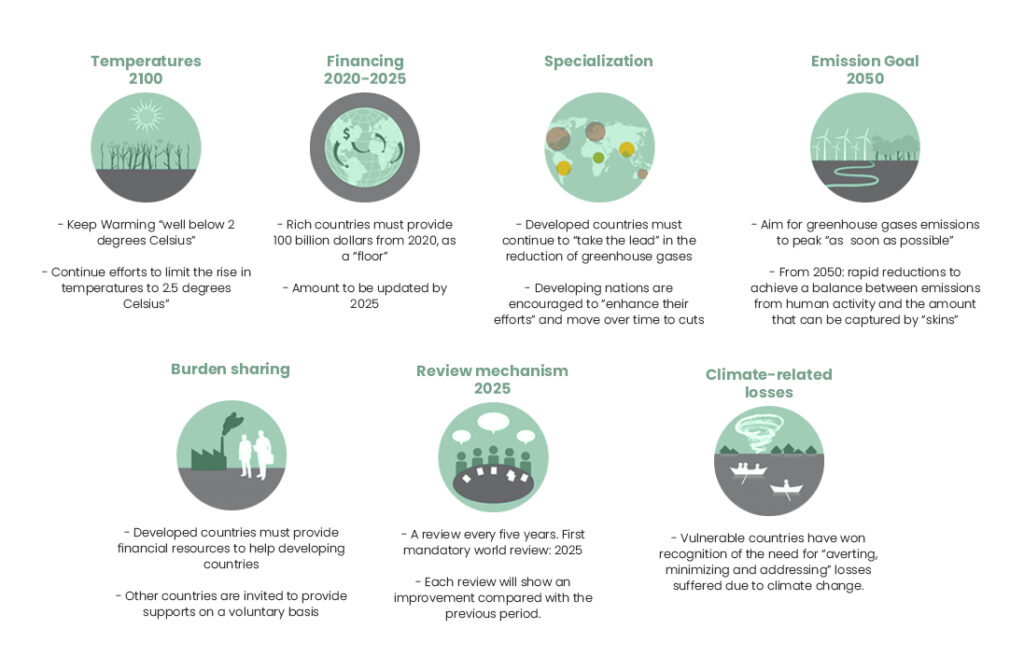

The Paris Agreement 2015 is the benchmark international treaty that establishes and governs climate action and adaptation efforts. It is the document that brings all parties to the table and establishes standards and reporting requirements. Out of 197 parties at the United Nations Climate Change Conference (UNCCC), 188 have ‘ratified’ the agreement, meaning they are mandated to at minimum “report regularly on their emissions and on their implementation efforts”. Out of the countries that have not ratified, only Iran (1.66%), Turkey (1.04%) and Iraq (0.48%) are significant emitters of Greenhouse Gases (GHG).The United States (13.92% of global emissions) is set to rejoin the agreement as soon as Biden takes office (Jan 20, 2021). This ubiquity makes the Paris Agreement the standard-bearer for discussions on climate action and a great starting point for analyzing progress and plans. If interested in a brief explainer, review this interactive that provides the finer points of the Paris Agreement. Pakistan (0.52% of global emissions) signed the agreement on the first day it was open for signatures, and has ratified it as well. This means Pakistan is subject to the Paris Agreement goals:

The Paris Climate agreement: key points

Source: Agence France-Presse

The UNCCC takes place every year – the 2020 conference, initially scheduled for November 2020 was going to be the first 5-year review after the Paris agreement and would have provided a whole host of country wise updates, through their Nationally Determined Contribution (NDC) submissions. However, due to the pandemic, the conference has been moved to 2021 – so let’s look at information that is available, primarily, preliminary submissions by Pakistan, called the Intended Nationally Determined Contribution (INDC), submitted in November 2016, and actions Pakistan has taken to mitigate the risks since then, along with the climate change chapter of the Economic Survey 2020.

Pakistan in Paris

Pakistan’s INDC submission is a surprisingly (in a good way) thorough document. It deals with almost all the areas that necessitate attention to avert the worst of climate change, acknowledges all the sectoral realities and their implications to Greenhouse Gas (GHG) emission till 2030, while also stating the economic realities of limited fiscal space (budgetary constraints) and balancing economic growth aspirations (ambitious assumptions not withstanding). The document concludes noting that “actions can be intensified in coming years with expected availability of international climate finance, technology development and transfer, and capacity building”. It also acknowledges that many of the actions taken over the past 5 years have been at the provincial level due to the 18th Amendment. Let us see if Pakistan has made any progress toward securing these climate action goals in the recent past.

Quaid-e-Azam Solar Park

The Good

In 2015, The Quaid-e-Azam solar park was inaugurated, billed as the first large scale solar installation in Pakistan directly supplying power to the National Grid, aiming to jumpstart the transition to hydrocarbon free electricity generation. In hindsight, this was a wise project to invest in, building solar infrastructure and enabling knowledge transfer for Pakistan. It also contributed to the creation of a market for solar energy, and enabled many local companies to startup and begin offering home base solar solutions, leading to an increase in solar energy capacity, aided by ‘net metering’. Most importantly, according to the International Energy Agency today solar is the cheapest form of energy in most places on Earth.

This holds true for Pakistan as well, with solar being the better option vs wind (the other ‘renewable’) as well, meaning it not only makes environmental sense, but economic sense as well. The cost required to generate a single kWh of energy is 65,000 Pakistani rupees (PKR) in the case of solar energy, while this is PKR 120,000 in the case of wind energy. Similarly, the average life span of solar PV is 25 years. While it is only 10-15 years for wind turbines. Solar PV do not have any maintenance cost while it is PKR 3.5/h for wind energy plants.

The Bad

The solar park was initially planned with a 1,000 MW capacity, envisioned as ‘the world’s largest solar farm’ – but after numerous administrative hiccups and amidst waning political will, it has not moved past 400 MW setup, with no signs of further progress, limiting the impact the solar park has on the distribution of energy in Pakistan’s grid.

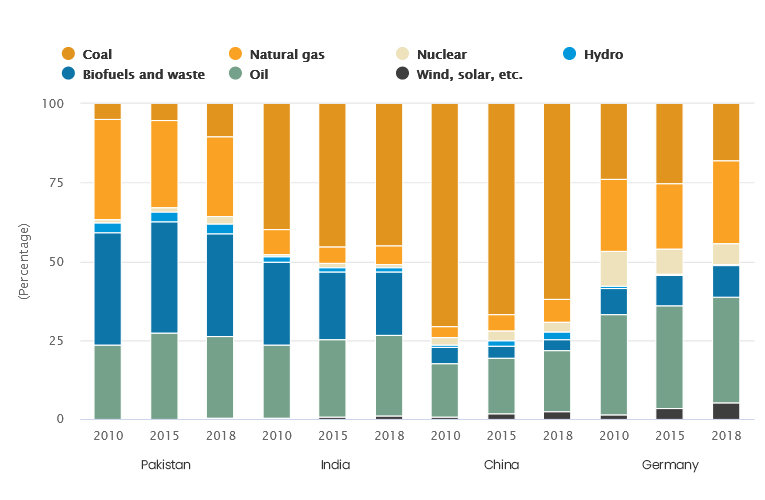

Looking at the distribution of energy sources and their progression over time, Pakistan doesn’t seem to fare too badly vs its much larger neighbors, India and China, although biofuels and waste account for a large percentage, mostly accounted for by rural consumption. This percentage is likely to fall as rural areas receive grid connections. Pakistan’s wind and solar make up 0.3% of total energy supply while the same proportion is 1.1% for India, 2.5% for China and 5.3% for Germany as of 2018.

Total Energy Supply by Source (ktoe)

Pakistan has limited supply of wind and solar energy but extensive use of biofuels

Pakistan India China Germany

Source: International Energy Agency

Lastly, the location choice for the solar park means that the solar panels receive a lot of dust, which reduces their efficiency. To counteract this, a lot of water is used to clean the panels – which for an already water stressed country should be raising alarm bells. Better design and forethought could have prevented these inhibitions and made the solar park a true success story for climate action.

Afforestation Measures – AKA Tree Plantation ‘Tsunamis’

The Good

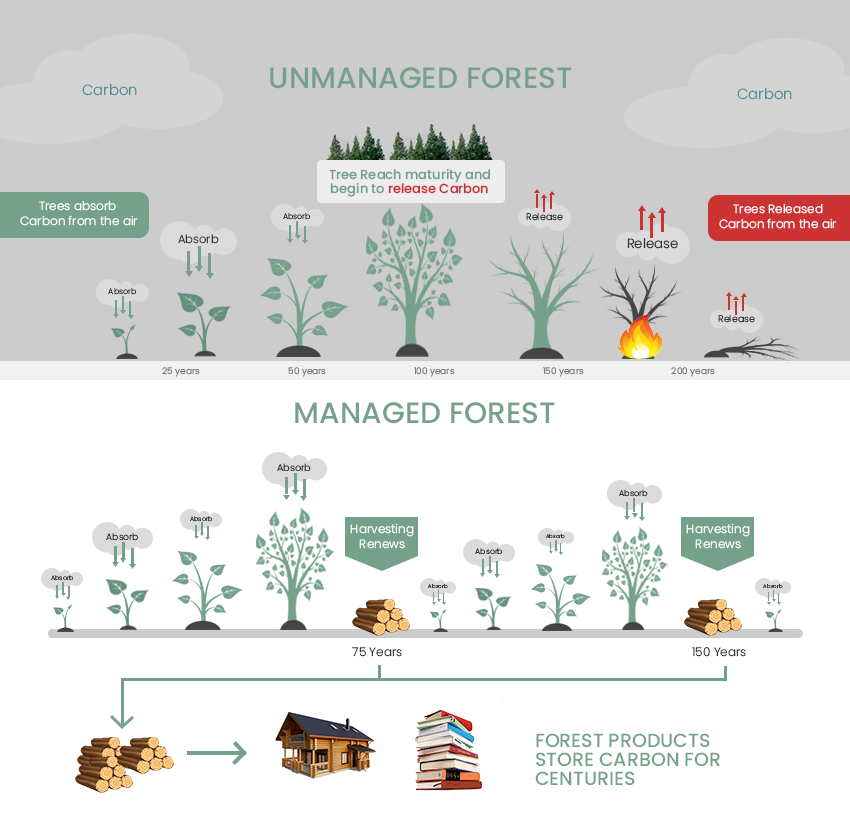

In 2017, the KPK province achieved its billion-tree target ahead of schedule, adding 350,000 hectares of trees. This is a significant addition, given forests covered between 4 and 5 million hectares in 2012. This was important, because this success is what prompted the 2018 federal plan to plant an additional 10 billion trees nationally- roughly an additional 6 million hectares – doubling the current coverage. Forests are the most effective naturals mechanisms for carbon ‘sequestration’ – they act as carbon ‘sinks’ – effectively removing carbon from the atmosphere, thus reducing the concentration of Greenhouse Gases (GHG).

Forest Carbon Cycle

Mitigating the effects of climate change through forest management

Source: West Fraser

While deforestation is still a big problem for Pakistan, these ‘tsunamis’ are steps in the right direction. Between 2001 and 2019, Pakistan lost 9.61kha of tree cover, which was almost 1% of the total and equivalent to 2.88 Mt of CO2 emissions.

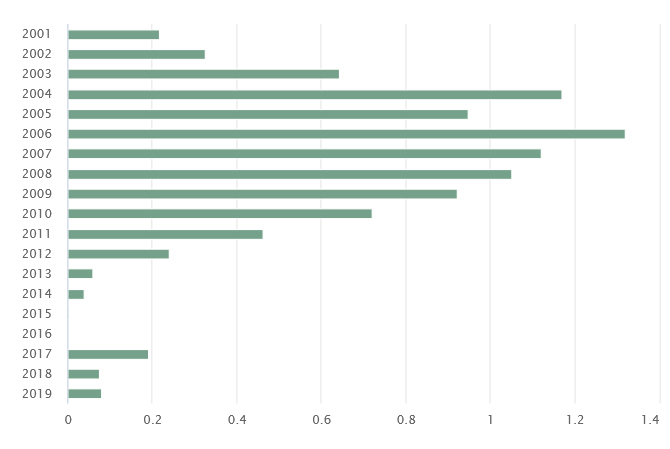

Of this loss, 90% came from KPK and FATA, mostly because alternative sources of energy are not readily available, leading to felling of trees. Additionally, 15% of the total tree felling directly led to deforestation in the affected areas. But as apparent from the below graph, the tree cover loss has dramatically reduced in recent years – with consistent focus on this issue, it is fair to say this is one problem Pakistan has a handle on.

Tree Cover Loss in Pakistan (kha)

Pakistan has successfully reversed the trend of deforestation in recent years

Source: Global Forest Watch

The Bad

It is important to stress that tree plantation, although a net positive, doesn’t perfectly substitute for conservation of the natural environment, which should always be the first priority –exploitation of natural reserves can’t continue unabated while holding up these ‘tsunamis’ as placeholders for environmental action. One of the major concerns regarding the tree plantation programs is that they should be the ‘cherry on top’ – the actions taken after major contributors are addressed.

Electric Vehicle (EV) Policy

The Good

The Pakistan Electric Vehicle Policy, after facing numerous delays and roadblocks, was finally passed in 2020. The main aims of the policy are to jump-start the EV infrastructure development in the country, allowing for development of ‘green’ sectors and businesses. The rationale is to have this infrastructure and market setup in the Pakistani economy by the time owning an EV vehicle becomes cost comparable to a fossil fuel powered vehicle, which according to this McKinsey report, should be by 2025.

EVs are one of the most promising technologies in the fight for climate action. Unequivocally, EVs are better for the environment, provide a better user experience and are fast becoming much more cost effective. Developing infrastructure like fast charging grids in the country will incentivize the industry locally and bring those gains already realized in the developed world to Pakistan as well. For anyone interested, this is a very comprehensive study that proves that over the life of an electric vehicle, from sourcing materials, through manufacture, use and disposals, EVs are environmentally superior to their fossil fuel counterparts. The study is somewhat technical so you can listen to this instead as well, for a broad breakdown on the EV economy.

The Bad

The initial policy proposal was far reaching and included cars as well, but the policy that got approved excluded cars, most likely due to lobbying from the oligopolistic car industry – instead focusing on two and three wheelers, as well as buses and trucks. This both limits the benefits from the policy and ignores the fact that SUVs are one of the leading causes of emission increases globally.

A major factor that affects carbon savings accrued from EVs, is the source of energy powering a geographies electric grid. Pakistan has, in the past decade ramped up electricity production to finally have a semblance of constant electricity supply in a majority of the country. However, this increased generation requirement was primarily met with increases in thermal generation (coal, natural gas and oil), which means EVs recharging from the grid will be fed by a grid that is 65% ‘dirty electricity’. Similar investments in renewables or cleaner sources instead could potentially have saved Pakistan a lot more money in the medium and long run, by saving on fuel costs as well.

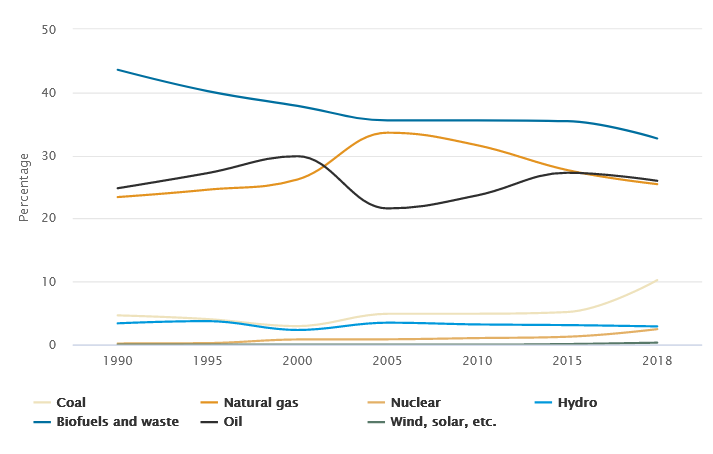

The increase in thermal consumption is apparent when total energy utilization is analyzed. While Pakistan’s total energy usage has grown by 158% from 1990 to 2018, total thermal generation has grown by 201%. The contribution of coal has doubled from 5% of total energy supply to 10%. These realities limit the climate action and positive environmental impact that even an established EV network can hope to have.

Total Energy Supply in Pakistan by Source (%)

Contribution of ‘dirty’ energy sources, specifically coal, has risen in Pakistan

Source: International Energy Agency

Ecosystem Restoration Fund (ESRF)

The Good

In Dec 2019, at the 2019 UNCCC (called COP 25), Pakistan launched its ‘Ecosystem Restoration Fund’ (ESRF), aimed at driving development actions in line with climate science. The fund is a nature-based adaptation initiative focusing on:

- Afforestation

- Recharge Pakistan – Integrated water management

- Conserving Biodiversity & Mitigating Land Degradation

- Conserving Marine Life & Promoting Blue Economy

- Promoting Eco-Tourism

- Electric Vehicles

Although the fund has not existed for a significant duration in ‘normal times’ – promising moves are being borne from it. The World Bank has agreed to fund the 5 year “Pakistan Hydromet and Ecosystem Restoration Services (PHERS) project”, worth $188 million. The funding will go some way to alleviating budgetary constraints for climate goals and broadly aims to fund adaptation to new climate realities that have already occurred, mitigation of future affects and to enhance policy infrastructure outlined in the INDC.

Specifically, it targets “attaining Land Degradation Neutrality (LDN) by restoring at least 30% of degraded forest, 5% of degraded cropland, 6% of degraded grassland (rangeland) and 10% of degraded wetlands in Pakistan by 2030”.

The Bad

This report from 2017 determined that Pakistan’s spending (federal and provincial) on climate action is on average about 8% of total budget, which is a significant amount. However, this amount will still not be enough for the scale of challenges this generational problem poses. External funding will be a necessary and important component to Pakistan’s efforts at building climate resilience, and will augment the federal and provincial budgets, enabling faster progress.

To answer the question we started with – Pakistan has made some progress, piecemeal and in bits here and there, but work is being done. Is it enough? Not at all. Are we doomed? Not if we demand more action and continue to focus of things that we can control. There is some very recent encouraging news on this front from the Prime Minister as well, continuing to stress the gravity of the problem. In the next article, the last of this series, we will look at some areas where investment would likely give the highest returns – while also sharing information about what individuals can do on a personal level to contribute to solving this global problem.