In just under a month’s time, the eyes of the world will be focused on Scotland, as senior politicians from across the globe convene in Glasgow to negotiate the acceleration of efforts to tackle climate change. The 2021 United Nations Climate Change Conference (or COP26) will be the most important climate summit since the landmark Paris Agreement was ratified at COP21 in 2015.

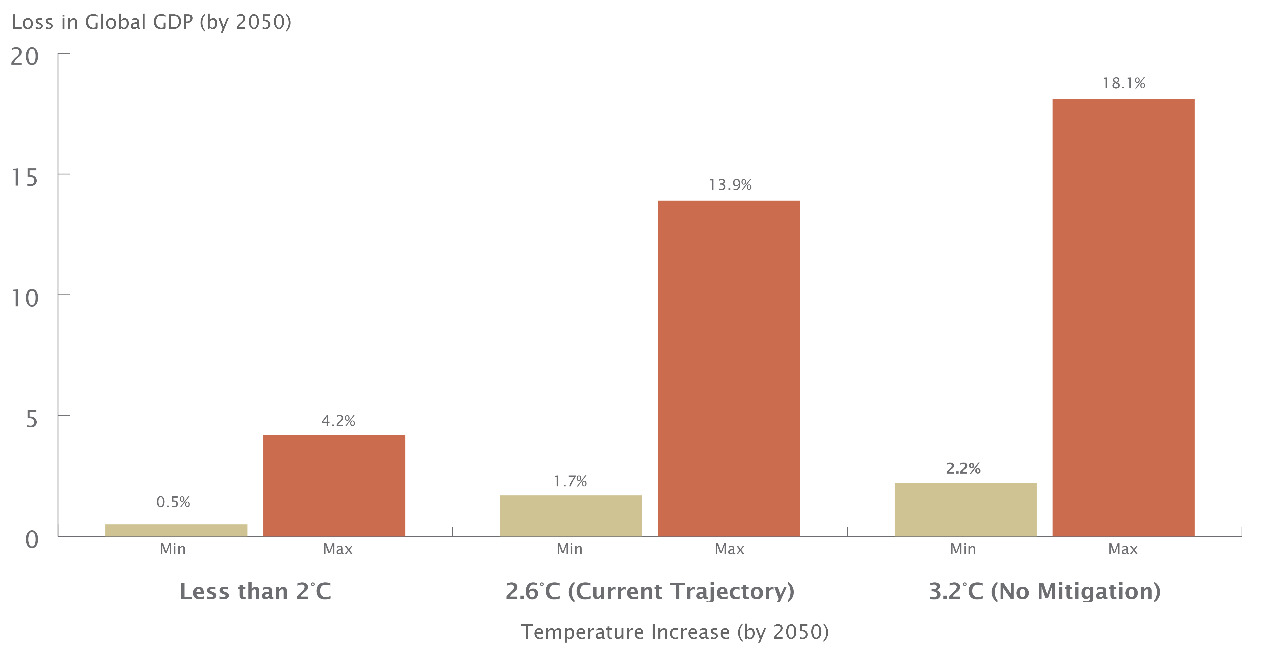

To limit global warming to 1.5 °C, as agreed in Paris, carbon dioxide (CO2) emissions must fall by about 45 percent by 2030 from a 2010 baseline. As the figure below shows, there are significant financial repercussions of increasing temperatures. More so, such changes will not be uniform, with developing countries expected to bear the brunt of climatic changes.

Global GDP will be significantly impacted by climate change in the coming years, especially if no mitigating steps are taken

Source: Swiss Re Institute, MP Analysis

Note: The range in values can be attributed to the presence of “(un)known unknowns”, i.e., factors such as disruption to global supply chains and trade, migration, and biodiversity, which cannot be exactly quantified, yet will undoubtedly impact GDP as temperatures rise.

International impact of climate change

In order to understand the magnitude of the problem at hand, it is important to understand the immediacy and gravity of the situation. According to a recent report, global average temperatures were 1.1° Celsius above pre industrial average by 2019. The consequences of such a development were:

- 2019 concluded a decade of exceptional global heat, retreating ice and record sea levels driven by greenhouse gases produced by human activities.

- Average temperatures for the five-year (2015-2019) and ten-year (2010-2019) periods are the highest on record.

- 2019 was the second hottest year on record.

- Total annual global greenhouse gas emissions reached their highest levels in 2018, with no signs of peaking.

- Based on today’s insufficient global commitments to reduce climate polluting emissions, emissions are on track to reach 56 Gt CO2 by 2030, over twice what they should be.

Urgent scalable action is needed to curtail rising temperatures

The 1.5° Celsius limit has been recognized as the defining limit to prevent catastrophic changes to the environment. In order to achieve this aim, emission need to be reduced by 7.6% every year till 2030. If the relevant stakeholders had acted a decade ago this figure was only 3.3%. Nations agreed to a legally binding commitment in Paris to limit global temperature rise to no more than 2°C above pre-industrial levels but also offered national pledges to cut or curb their greenhouse gas emissions by 2030. This is known as the Paris Agreement; an extension of the Kyoto Protocol.

If countries cannot agree on sufficient pledges, in another 5 years, the emissions reductions required will leap to a near-impossible 15.5% every year. The unlikelihood of achieving this far steeper rate of decarbonization means the world faces a global temperature increase that will rise above 1.5°C. Every fraction of additional warming above 1.5°C will bring worsening impacts, threatening lives, food sources, livelihoods and economies worldwide. Above 1.5° Celsius:

- Over 70% of coral reefs will die, but at 2°C, over 99% will be lost.

- Insects, vital for pollination of crops and plants, are likely to lose half their habitat at 1.5°C but this becomes almost twice as likely at 2°C.

- Over 6 million people currently live on coastal areas vulnerable to sea-level rise at 1.5°C degrees, and at 2°C, this would affect 10 million more people by the end of this century.

- Sea-level rise will be 100 cm higher at 2°C than at 1.5°C.

- The frequency and intensity of droughts, storms and extreme weather events are increasingly likely above 1.5°C.

Impact of climate change on Pakistan

Research has shown that the climate change-induced loss of wheat and rice crop production by 2050 would be USD 19.5 billion on Pakistan’s real GDP, coupled with an increase in commodity prices followed by a notable decrease in domestic private consumption. The important climate change threats to Pakistan include considerable increase in the frequency and intensity of extreme weather events, coupled with erratic monsoon rains causing frequent and intense floods and droughts. Projected recession of the Hindu Kush-Karakoram-Himalayan (HKH) glaciers due to global warming and carbon soot deposits from trans-boundary pollution sources, threatening water inflows into the Indus River System (IRS), pose a further worry.

Rising temperatures resulting in enhanced heat and water-stressed conditions, particularly in arid and semi-arid regions, could lead to reduced agricultural productivity. Meanwhile, increased intrusion of saline water in the Indus delta would adversely affect coastal agriculture, mangroves and the breeding grounds of fish. Threat to coastal areas would also increase due to projected sea level rise and increased cyclonic activity due to higher sea surface temperatures, potentially causing increased climate change-induced migration. These threats pose major survival concerns for Pakistan, particularly in relation to the country’s water security, food security and energy security.

What is the role of the private sector?

Considering the impact that climate change would have, the public and private sector need to improve resource efficiency while ensuring investment in environmentally and socially sustainable projects. Although the government is a key stakeholder in any discussion on climate change, the role of the private sector is equally important.

The following six sector solution plan focused on private sector interventions will go a long way to achieving the mitigation aims of the world collectively:

- The energy sector can reduce its emissions by 12.5 Gt. The private sector’s role in this can be to improve resource efficiency through embracing the opportunities that a transition to renewable energy will create across supply chains, setting a timeline to divest holdings in fossil fuel companies, and set decarbonization and net-zero carbon targets.

- Industry could reduce its emissions by 7.3 Gt each year by embracing renewable-energy based heating and cooling system, improving energy efficiency and addressing methane leaks.

- Food production solutions can reduce emissions by 6.7 Gt by shifting to sustainable growing technologies and better water management. Reducing food losses and switching to more sustainable diets can help reduce emissions by 2 Gt per year.

- Halting deforestation and improving wetland management can help reduce emissions by 5.3 Gt annually. It can also improve air and water quality, boosts biodiversity, bolster food security and shore up rural economies.

- The transport sector is responsible for one quarter of all greenhouse gas emissions. These are estimated to double by 2050. Emissions can be reduced by 4.7 Gt by embracing electric vehicles, both privately and in public transit system, creating pedestrian friendly cities and other forms of non-motorized transport.

- It is estimated that by 2030, buildings will account for 12.6 Gt of energy related emissions. Upgrading current infrastructure and ensuring that new homes and cities are not carbon intensive can reduce emissions by 5.9 Gt annually.

Environmental Social & Governance (ESG) goals: Good for companies and the environment

There have been a number of studies looking at the relation between companies’ environmental, social, and corporate governance practices (ESG) and their financial performance. The vast majority of them find a direct link: companies that do good by the environment, their labor force, and communities, do well financially. IFC recently looked at the performance of 656 companies in its portfolio and found that companies with good E&S performance tend to outperform clients with worse environmental and social performance by 210 basis point (BPS) on return on equity (ROE) and by 110 bps on return on assets (ROA.). IFC also found that reporting really matters: firms with a well-established practice of reporting on more than half of SASB material sustainability indicators outperform firms with a weak reporting culture. This is in line with the findings by Harvard Business School that reporting on material issues is associated with increases in firm value.

A strong ESG proposition links to value creation in five essential ways:

| Strong ESG proposition | Weak ESG proposition | |

| Top-Line growth |

Attract B2B and B2C customers with sustainable products

Achieve better access to resources through stronger community and government relations |

Lose customers through poor sustainability practices or a perception of unsustainable/unsafe products

Lose access to resources because of poor community and labor relations |

| Cost reductions |

Lower energy consumption

Reduce water intake |

Generate unnecessary waste and pay correspondingly higher waste disposal costs

Expend more in packaging costs |

| Regulatory and legal interventions |

Achieve greater strategic freedom through deregulation

Earn subsidies and government support |

Suffer restriction on advertisement and POS

Incur fines and penalties |

| Productivity uplift |

Boost employee motivation

Attract talent |

Deal with social stigma which restricts talent pool

Lose talent as a result of weak purpose |

| Investment and asset optimization |

Enhance investment returns by allocating capital for the long term

Avoid investment that may not payoff in the long term because of environmental concerns |

Suffer stranded assets as a result of premature write-downs

Fall behind competitors who are energy efficient |

Conclusion: Redefining the calculation of value

On a countrywide scale, GDP is usually cited as the most fundamental metric of economic performance. However, its parochial nature has been criticized for its inability to take stock of natural capital. A measure of inclusive wealth is thus imperative; a measure that combines the accounting value of produced, human and natural capital. Work in this regard has accelerated significantly in the last two decades with China adopting a measure termed the ‘Gross Ecosystem Product’. Similar metrics are in the works in different countries across the globe. But, with natural capital accounting still in infancy and significant design and measurement challenges remaining, work needs to be done to boost reporting and assessment frameworks that better tally the worth of soil, trees, water, air, minerals and other resources.

As for the private sector, “sustainability” measures by companies need to go beyond mere optics. They should be an enduring long-term investment, not just because it is the right thing to do, but also because it leads to substantial returns in the long run. As this movement escalates, we hope that companies in Pakistan are on board to take steps that might not only be imperative for their respective organizations, but for the country as a whole.