Winter in Pakistan brings its own rituals; ridiculously patterned blankets are dragged out of storage, thelas selling chicken corn soup become ubiquitous, while crates filled with firewood start appearing at building entrances. Over the last few years however, there has been one rather unpleasant tradition associated with the onset of cold weather in our urban areas. Eyes burning, sore throats, and dry coughs—I’m talking of course about smog.

Understanding smog season

This thick mixture of water vapour and various pollutant gases envelopes Pakistan’s cities starting every October, usually lasting till February. Lahore, along with India’s Delhi, are two of the most infamous examples. But increasingly, this low-lying haze has started manifesting itself across the country; ranging from Peshawar in the northwest, to Karachi in the south.

So, what exactly is smog? It is a specific type of air pollution created by the release of pollutant gases into the atmosphere. Nitrogen dioxide (NO2), sulfur dioxide (SO2), carbon monoxide (CO) and particulate matter (PM) mix together, reacting with sunlight as well as each other, to create those familiar thick layers of grey.

While these pollutant gases affect air quality year-round, smog is more likely to appear in the winter months due to a phenomenon known as winter inversion. In the summers, warm air close to the surface of the earth rises and disperses into the upper atmosphere, taking polluted air with it. In the winter, that air near the earth’s surface is cooler, and thus heavier, so polluted air continues to accumulate in the atmosphere close to land. Geography and topography can also have an impact, as Lahore’s landlocked nature, and Peshawar’s location in a valley surrounded by mountains make them both more susceptible to smog.

Quantifying air quality

The most common yardstick to approximate air quality is PM 2.5. This measures the quantity of particulate matter in the air that is less than 2.5 micrometres in width, and is the main cause behind the haze associated with smog. A higher PM 2.5 reading indicates the presence of more particulate matter, thus meaning the air is more polluted. New WHO guidelines issued in 2021 state that, on an annual basis, PM 2.5 should not be higher than 5 µg/m³. Punjab air quality standards are a bit laxer, as they allow PM 2.5 pollution to be up to 15 µg/m³. In reality, Pakistan’s air quality is considerably inferior to both those standards. In 2019, Lahore’s PM 2.5 score was 50 µg/m³. Karachi was even worse, nearly 13 times over the WHO standards at 63 µg/m³.

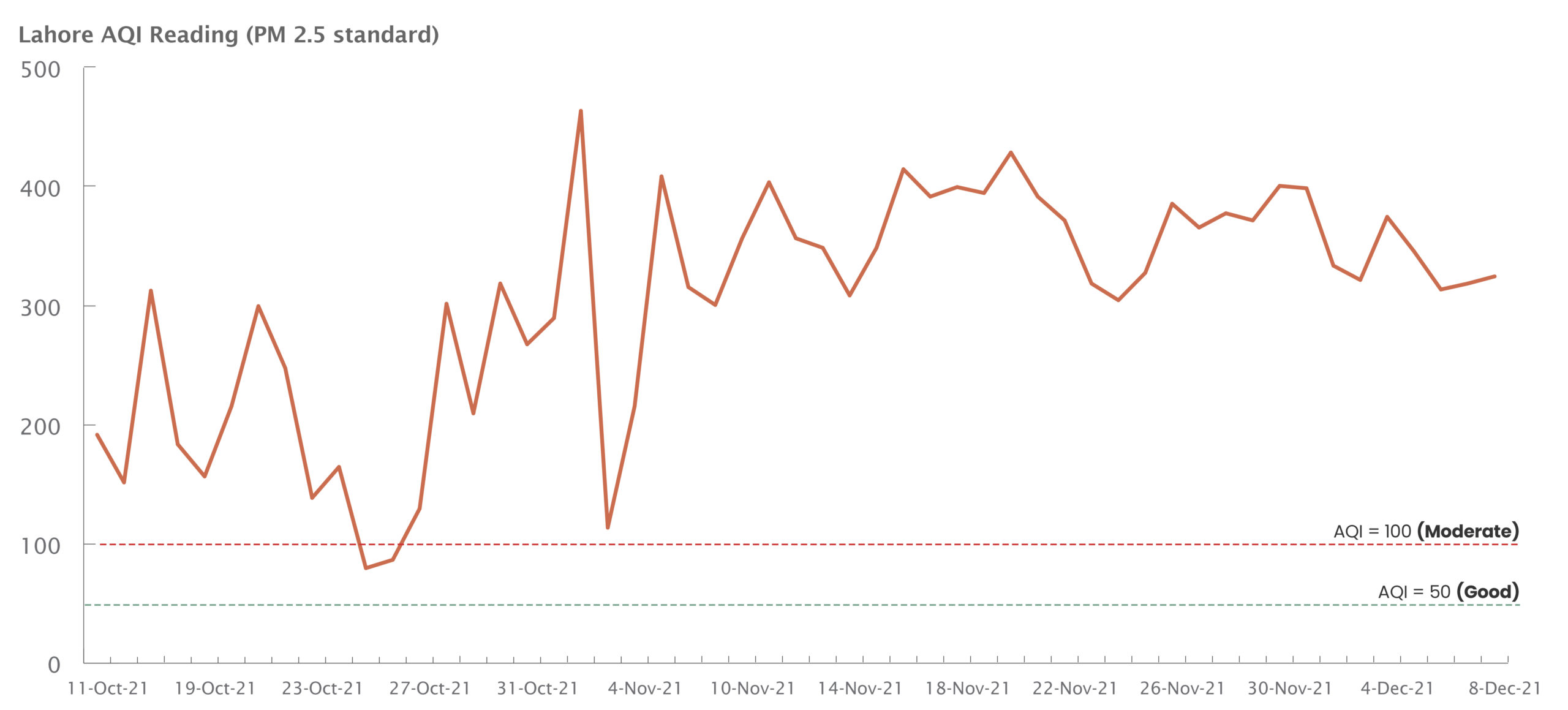

PM 2.5 readings can also be used to calculate an area’s Air Quality Index. This is a method used by the United States Environmental Protection Agency that has gained considerably popularity worldwide. According to the US, an AQI score below 50 indicates that air quality is good, while a score above 100 is unhealthy for people. Again, local standards are found wanting, as the Government of Punjab’s Smog Policy of 2017 considers an AQI reading of up to 200 to be satisfactory. In any case, Lahore’s AQI readings over the past two months exceed both those metrics.

An AQI reading above 100 is considered unhealthy. Lahore’s air quality over the past two months has exceeded this figure many times over.

Source: EPA Punjab, MP Analysis

Health effects

Poor air quality poses a pressing threat to the short and long-term health of urban residents. The small size of PM 2.5 particles means that they can reach deep inside our lungs, and even into our bloodstream, causing cardio-respiratory issues such as asthma, bronchitis and black lung. Nitrogen dioxide similarly causes lung function problems. It is also a key component in the making of PM 2.5 and ozone (not to be confused with the ozone layer), which can trigger asthma and cause breathing problems. Sulfur dioxide, on the other hand, is responsible for irritation in eyes and affecting the respiratory system. Lastly, carbon monoxide reduces blood’s ability to carry oxygen. For individuals already suffering from pre-existing ailments, this can exacerbate symptoms even further.

These pollutant gases are having a very real impact on the lives of Pakistanis. A study in 2015 found that 22% of annual deaths in Pakistan are due to pollution, the vast majority of which can be attributed specifically to air pollution. Another report by the University of British Columbia in 2019 found that the lives of children in South Asia are cut short by 2.5 years due to air pollution. Conversely, an analysis by the University of Chicago stated that Pakistanis could gain nearly four years in life expectancy if air quality in the country met WHO standards.

Causes of poor air quality

It has become convenient for the authorities to blame crop residue burnings in India for Punjab’s smog season. This doesn’t add up for three reasons. First, crop residue burnings take place in Pakistan too, so the buck can’t just be passed across the border. It also doesn’t explain the appearance of smog in Karachi, located far away from Indian Punjab. Second, poor air quality is consistently a problem, so blaming a seasonal activity can’t account for the entire calendar year. Third, the Government of Punjab’s own R-SMOG report from 2017 sheds light on the local factors contributing to the province’s poor air quality.

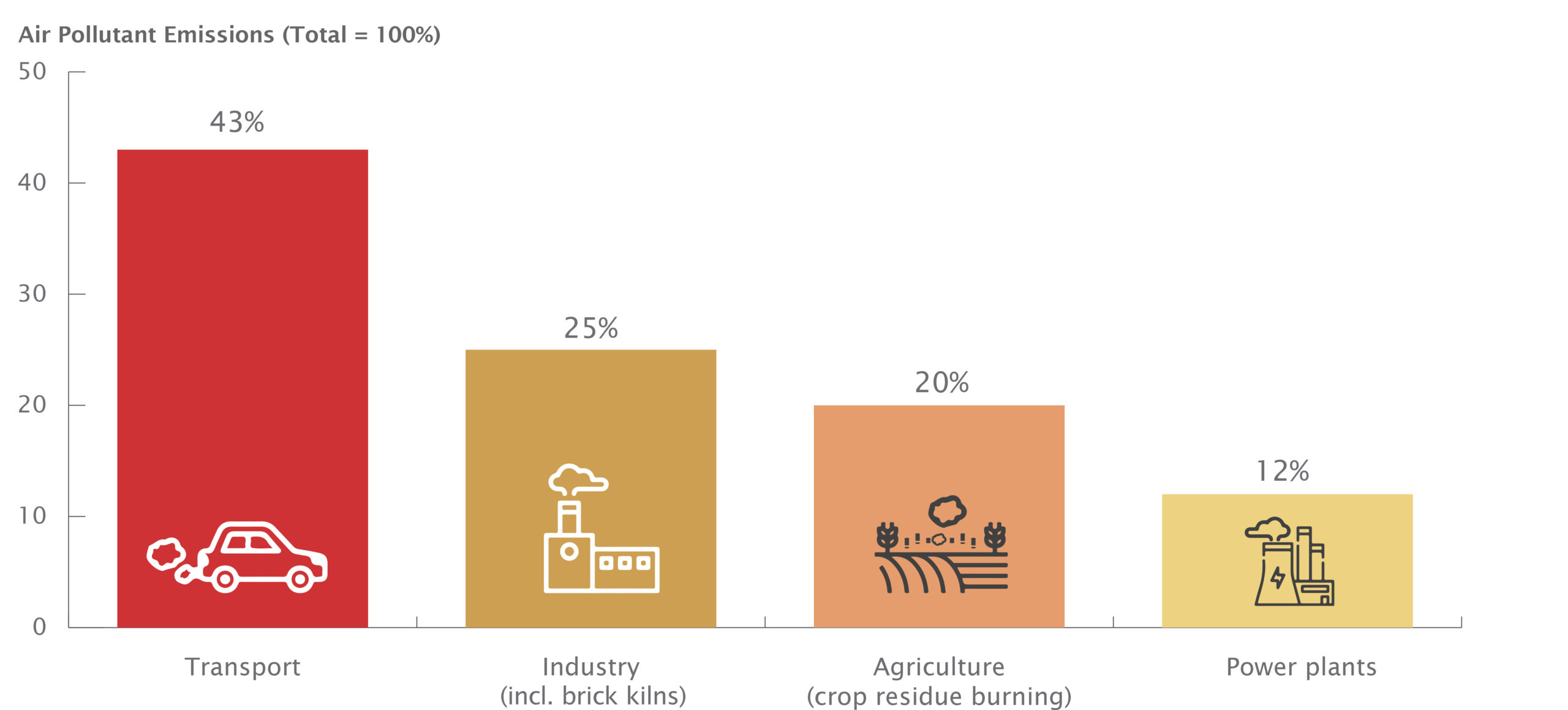

What is polluting Punjab’s air?

A government report from 2017 has some answers—and it’s not India.

Source: R-SMOG Govt of Punjab, MP Analysis

With crop residue burnings making up only a fifth of all emissions, the difference between government hyperbole and reality is apparent. To examine these percentages further, the vast majority of the transport sector’s emissions are in the form of carbon monoxide, followed by a chunk of nitrogen oxides. Crop residue burnings in agriculture too mostly produce carbon monoxide. Most emissions from power plants, meanwhile, are in the form of sulfur oxides due to their use of fossil fuels such as furnace oil and coal. Similarly, the industrial sector emits significant amounts of sulfur oxides and PM 2.5 pollutants due to the use of low-grade, high-sulfur coal and diesel generators, especially in the brick kiln and cement industries. Understanding this breakdown is critical to devising effective solutions for improving air quality.

A better future is possible

What are some practical steps that the government could take in each sector to improve air quality?

When it comes to crop residue burnings, a government order simply banning the activity is not enough. That order is neither followed or enforced. It also doesn’t get at the root cause of the problem, which is that farmers burn this residue not because they like to do so, but because it is the cheapest away to clear out their fields for the next growing season. If the government truly wants to solve this problem, it needs to allocate financing and technical help for poor farmers to adopt more sustainable practices.

Similarly, trying to ban “smoky cars” from the city is an ineffective tactic. People own old cars out of financial necessity rather than choice. Introducing regulations mandating catalytic converters and vehicle emission limits are important in reducing carbon monoxide, but the government has to once again work with owners of cars and old diesel-run public buses to help them transition towards newer and cleaner technology. Shifting consumption away from high-sulfur Euro II fuel is also an important step. The government had apparently mandated all petrol consumption and imports to move to the higher-quality Euro V standard by January 2021, but that has yet to happen. In the medium to long-term, the government also needs to do more to improve public transit options in cities so that there are fewer vehicles on the road to begin with.

Finally, in the industrial and power sector, short-term steps such as adopting zig-zag technology in brick kilns can make a difference, but only if an accompanying ban on traditional kilns is enforced. In the long run however, there is no alternative to moving power generation and consumption away from furnace oil and coal, and towards renewable energy and less-polluting natural gas.

The decisions taken by the government will inform whether we face a bright future, or a lifetime of gloomy haze.