What if the one-time Ehsaas cash transfer was to become permanent?

There is a moral and economic argument to give most Pakistanis an unconditional basic income each month.

You may remember a popular meme from a few years ago titled “we live in a society”. Often accompanied by a picture of the Joker, the template was meant to be a satirical look at society’s many contradictions and flaws. One of those contradictions that we passively accept in our daily lives is the extreme level of inequality in society, whereby some people have enough wealth to live comfortably over generations, while large segments of our population struggle to simply survive every day. And as the numbers tell us, those segments of the population are indeed quite large.

According to official statistics, 24% of our population lives below the literal poverty line. Another 20% is just above that mark, but is extremely vulnerable to slipping below the line at any moment. In fact, that’s exactly what the government estimates happened to many in this segment in Covid-19 times, when lockdowns and loss of work meant that living standards dropped even lower for these 44% of Pakistanis. If one looks at multidimensional poverty, which also considers deprivation in health, education and living standards, then it is estimated that 57% of Pakistan’s population is socioeconomically vulnerable. That’s about a 115 million people, or more than 1 in 2.

Consequences of poverty

This stark level of poverty impacts other important fields too, such as savings, where most Pakistanis do not have any substantial savings to utilize in case of an emergency. Many actually have negative savings, i.e., they are heavily in debt, as they have had to borrow money just to get by.

And then there’s nutrition. 40% of children under the age of five in this country are stunted, 18% are wasted, and 29% are underweight. That’s not exactly a surprise; the government estimates that a family needs to spend roughly 3000 rupees per person monthly to meet minimum nutrition standards. But families in the bottom 20% of income earners mathematically can’t meet that standard even if they spend their entire income on food and nothing else.

All these problems are interlinked, with one (fairly obvious) recurring theme: not enough money. So, here’s a thought: What if we tried to change that, by just handing people money?

Universal basic income

This is the thought process behind an idea that has rapidly taken root across the world; that all adult citizens are entitled to a set amount of money every month from their government as a means to supplement their income and boost their living standards. There is a moral argument that can be made for this “basic income”, in the same way that can be made for the welfare state; namely that we live in a society, and as such, have an obligation to help out those in need. But there is also a persuasive economic argument that, contrary to traditional wisdom, free money for people can be good, actually.

In recent years, various countries have experimented with a basic income. Some have made it unconditional; others conditional. Some have chosen a targeted group; others have included just about everyone. But while the design of the program itself has varied from country to country, nearly every program has had major success.

Basic income experiments around the world

The US government issued multiple “stimulus checks” to most of its citizens after the outbreak of Covid-19. An analysis of the most recent round of $2000 checks, for which most citizens were eligible (although those with higher incomes received less), found that food shortages fell 42% among households with children, overall financial instability fell by 43%, and frequent anxiety and depression fell by 20%. Research from Scotland similarly found that an expanded unconditional basic income would lift more than 80% of citizens below the poverty line out of poverty, while virtually fully eradicating child poverty.

In the pre-pandemic era, a nationwide randomized basic income trial carried out by Finland found that those participating not only benefited from better physical and mental health, but were also more likely to find work than those in the control group. A smaller-scale trial in Netherlands similarly found people receiving basic income to be more likely to work. And although neither trial was conclusive, another research paper studying several basic income schemes found that, on average, they strengthened work incentives for low- and middle-income households.

This may sound counterintuitive, but take a moment to examine your own motivations. I’m sure some of you reading this likely don’t need to work to have a roof over your head, or food to survive. Yet you still choose to work, maybe because you’re passionate about what you do, maybe because you’d otherwise get too bored, or maybe because you just like having some extra cash to spend. People have all kinds of motivations to work, and giving them some extra money each month won’t suddenly change that.

Findings from developing countries

Research regarding the benefits of a basic income isn’t limited to developed countries alone. An unconditional basic income experiment piloted in India’s Madhya Pradesh a decade ago found that giving each individual just a few hundred rupees a month led to hunger falling by 25%, child nutrition improving by 20%, and girls attendance in secondary school improving by 30%—all showing improvement relative to the control group. In fact, alcohol consumption was also reduced compared to the control group, with less economic stress attributed as one explanation.

A more wide-ranging study of conditional cash transfers in 27 low-to-middle income countries found that they had largely positive benefits for those enrolled. Many programs led to substantial reductions in poverty, helped buffer households from indebtedness caused by unemployment and illness, increased school enrolment, and also increased the bargaining power of women—as they were the primary cash recipients for the entire family in most programs. One of those programs is the Benazir Income Support Program (BISP), Pakistan’s version of a basic income that has existed for a decade, and which was recently expanded further under the current government’s Ehsaas program.

Benazir Income Support Program

BISP was launched in 2011 as a program targeted towards the poorest 15% segment of the population. It gave cash transfers equivalent to a little over 1000 rupees each month to a woman on behalf of her family, and despite the small amount, led to a lot of positive outcomes.

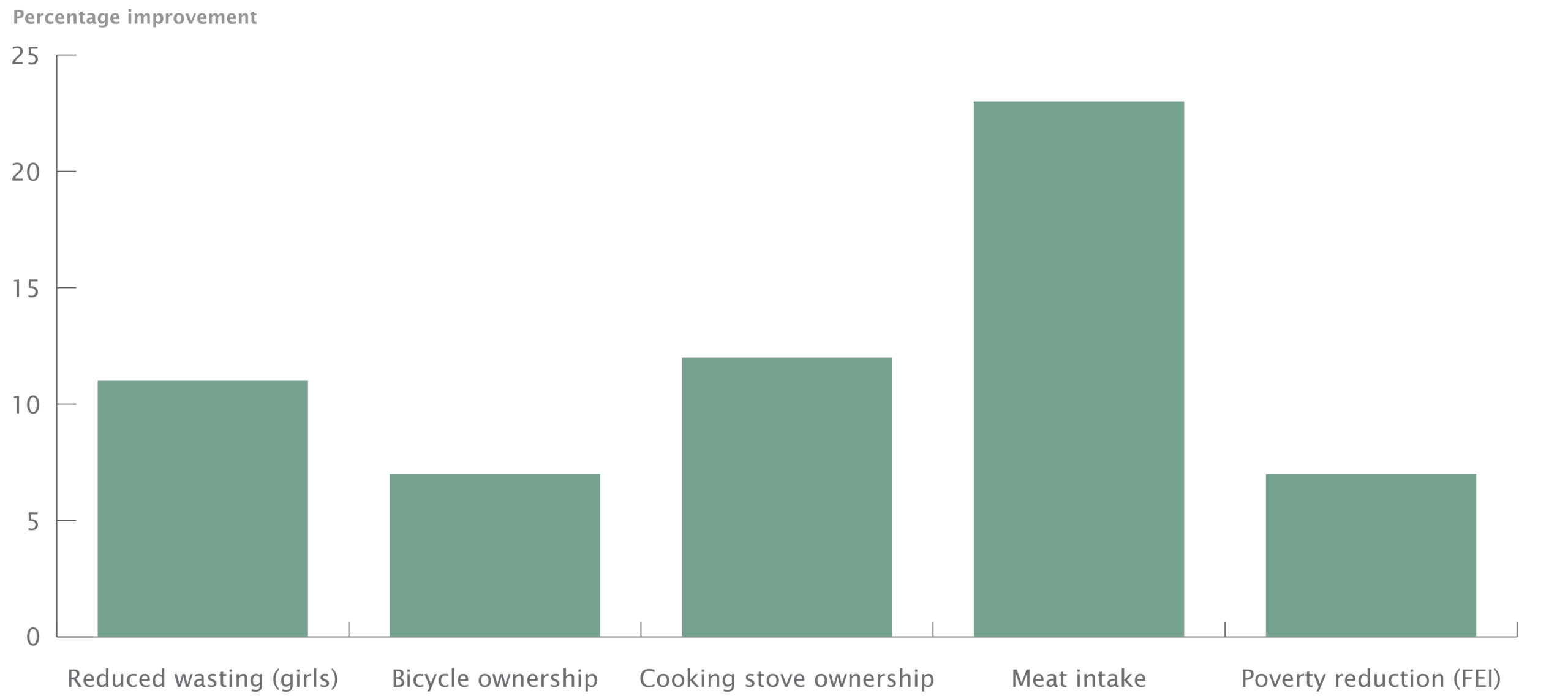

Over five years, monthly BISP cash transfers of merely PKR 1000-1500 per family had positive effects on nutrition, poverty reduction, and wasting (a measure of childhood stunting)

Source: Oxford/BISP, MP Analysis

Besides the improvements referenced above, the five-year analysis also found an increase in the number of women voting, as well as their power more generally—as in more than 70% of cases, women would decide how the BISP money would be spent. These findings were not limited to this report alone, as another World Bank report also found evidence of increased women empowerment through BISP.

A more recent follow-up report on BISP didn’t find as much improvement across all metrics, but it still showed that from 2011-2019, consumption expenditure amongst beneficiaries increased by 22%, and the percentage of those classified as ultra-poor fell from 64% (2011) to 39% (2019). However, overall poverty numbers still haven’t been impacted much by BISP.

This is partly because BISP gives too little money; at present, beneficiaries receive a little over PKR 2000 a month. For an average BISP beneficiary household on a monthly basis, this adds up to about PKR 200-300 extra spending per person, bringing them to a total expenditure of PKR 3,373 per person in 2019. Unfortunately, this isn’t enough to move the needle on overall poverty, as the poverty line for consumption expenditure in 2019 was PKR 3,881 per month. Secondly, it still targets a very narrow band of the population, i.e., the bottom 15%, even though it is established that at least half of all Pakistanis are vulnerable to poverty. This is where the Ehsaas program comes in.

The Ehsaas program

At the onset of Covid-19, the government decided to rapidly expand its Ehsaas cash transfer program. While the Ehsaas initiative already covers BISP, as well as other conditional cash transfer programs, the government took it a step further and decided to make a one-time PKR 12,000 payment to 17 million families, or nearly 100 million people, covering roughly half the population. The idea was to give a three-month supplementary income (PKR 4,000 each month) to families suffering from the economic effects of Covid-19 and its associated lockdowns.

At an official cost of PKR 144 billion, this cash transfer helped cover food expenditure for roughly three-quarters of the three months time period, if families spent as much as the poorest 20% of households. In other words, it basically gave families nearly enough money to not starve for three months. This was especially a boost for women, 12 million of whom were home-based workers making PKR 3000-4000 a month, income that they mostly lost in the economic slowdown. The question then becomes, why don’t we make these payments all the time?

Ehsaas, but make it permanent

The Ehsaas cash transfer was unprecedented in terms of the number of people it reached. It also showed the advantage of direct cash transfers vs. subsidies and other welfare programs which lose a lot of money in administrative costs and distribution wastage. By contrast, cash transfers have very low intermediary losses. The government already has a National Socioeconomic Registry, which has information on nearly 87% of households in Pakistan, with estimates of their welfare status and poverty levels. Much like the one-time cash transfer, this registry can be used to make seamless monthly payments to half of all Pakistani households, with the potential of expanding this program even further in the future.

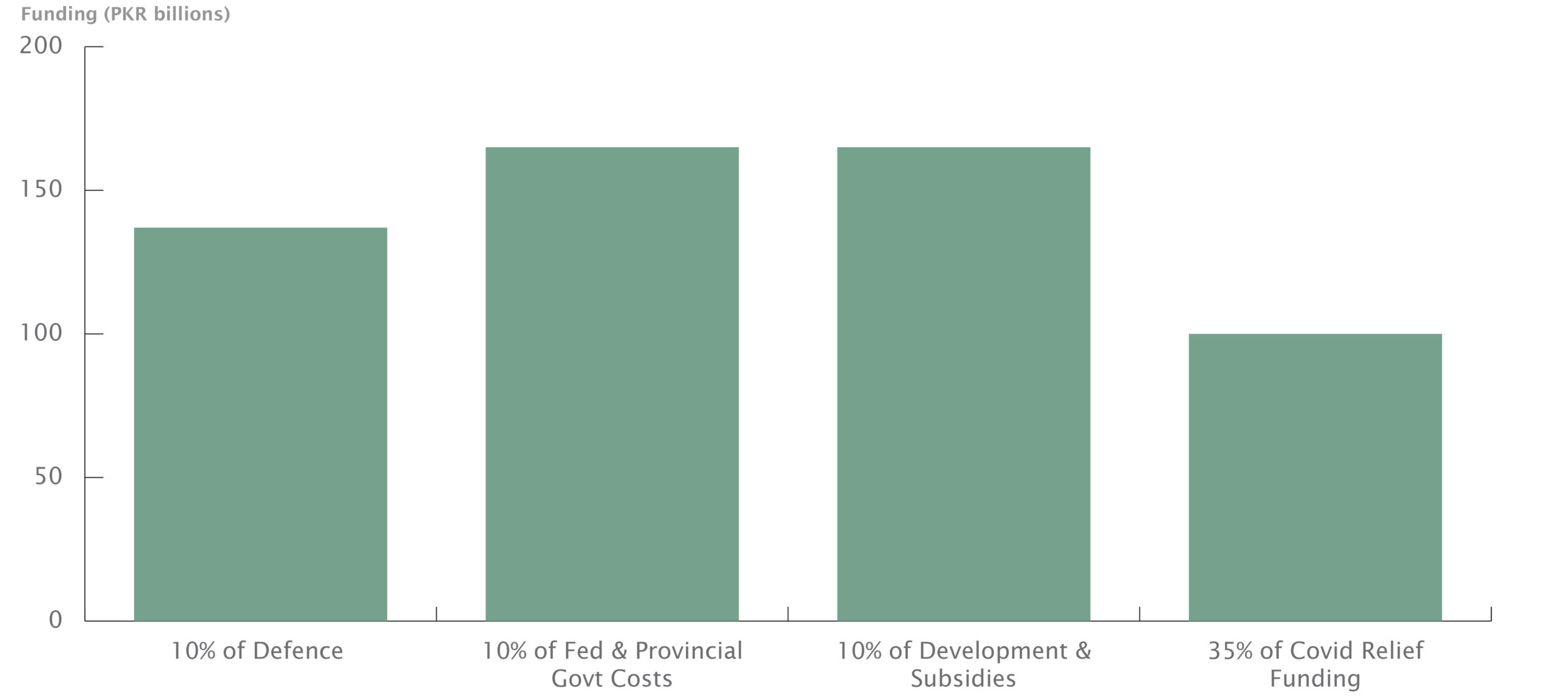

As a realistic starting point, the Ehsaas program can immediately start with PKR 4,000 monthly payments to the nearly 100 million people it has already identified as extremely vulnerable. Using the government’s own numbers on this, this would cost PKR 576 billion annually (144 billion for three months, multiplied by four). Can we afford that? It is certainly possible.

Permanent Ehsaas payments, i.e., giving half of all Pakistani families PKR 4,000 each month, would only cost 7% of our annual budget. Here’s how we could pay for it:

Source: Govt of Pakistan, MP Analysis

The cuts to existing government spending that would be required to make this program work are small, but not inconsequential. These figures are also completely hypothetical, as in reality, funding sources can vary; the World Bank, for example, is already partly funding cash transfer programs in Pakistan. The purpose, however, is to illustrate that these numbers are not insurmountable, even for a country in perpetually-constant financial stress.

Cash transfer programs, in Pakistan as well as around the world, have proven their efficacy in boosting poverty reduction, nutrition, women empowerment and more. If the current government is truly serious about addressing these issues, it would be well-advised to make its one-off Ehsaas cash transfer a permanent fixture.

One Comment