With a gross savings rate of 26.1%, Japanese policymakers over the years have struggled to encourage pro-consumption behavior amongst the populace. Having already suffered the “Lost Decade” in the 1990s owing to a usually high rate of savings relative to the OECD countries, the country experienced a similar phenomenon in the year 2021, primarily due to Covid-19. The pandemic-induced stimulus payments granted by the government to every eligible resident failed to increase consumer spending and, instead the majority of the payments went into savings’ accounts, further pushing the savings rate up.

While Japan struggles with its high savings rate, in Pakistan, our problem lies more in our abysmally low savings rate. This balance between savings and domestic consumption is key, and is one that countries around the world strive to achieve.

Why do countries save?

Relationship between savings and economic growth has been a point of interest for both policymakers as well as academics, with a potential causal relationship between the two variables studied exhaustively since the 1950s. Historical data, along with staunch observations of different open economies, led several economists such as Roy F. Harod and Evsey Domar to state that an economy’s growth rate can be measured in terms of the level of savings and capital, both of which act as a catalyst for sustained economic growth. This was named as the “Harod-Domer Model”, and although a decade later Robert Solow and Trevor Swan extended the model (Solow-Swan Model), the central assumption remained the same i.e., higher savings meant higher capital accumulation and thus higher economic growth.

The empirical evidence of a strong positive causal chain from savings to economic growth has been in literature. However, if a country has other sources of finances available such as easy access to low-cost credit and, is highly integrated with the international financial institutions, then domestic savings play a lesser role in promoting economic growth. This is because of the availability of alternate finance.

In Pakistan’s case, evidence exists of higher savings leading higher GDP growth. However, owing to a low gross saving rate, coupled with the country’s over-reliance on international financial institutions like IMF, World Bank, and foreign donors to compensate for the current account deficit, Pakistan has found it extremely difficult to fund the deficit solely from domestic savings. In order to diversify the sources of finance, an increase in domestic savings should be one of the primary priorities of the stakeholders involved.

Are we saving enough?

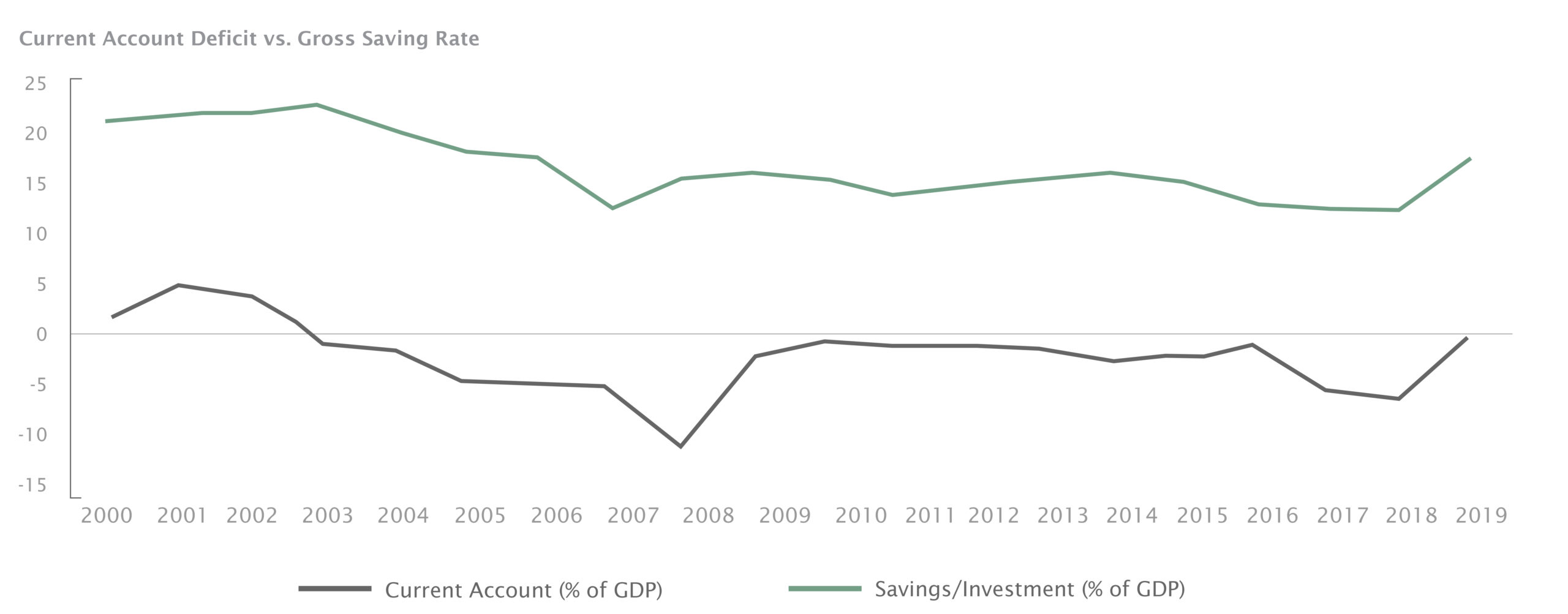

Pakistan suffers from one of the lowest gross savings rates in the world. As of 2019, Pakistanis saved 12.3% of GDP. For comparison, the world and South Asian average is 24.69% and 27.97%, respectively.

The country’s current account has been in near-constant deficit throughout the last 15 years. The trend can be coincided with the degree of savings (as a % of GDP). Despite maintaining a stable trajectory, savings rate has never been adequate enough to compensate for the current account deficit. In fact, it has actually declined since reaching its peak in 2003 at 24.5%.

Source: World Bank

Can it get any worse?

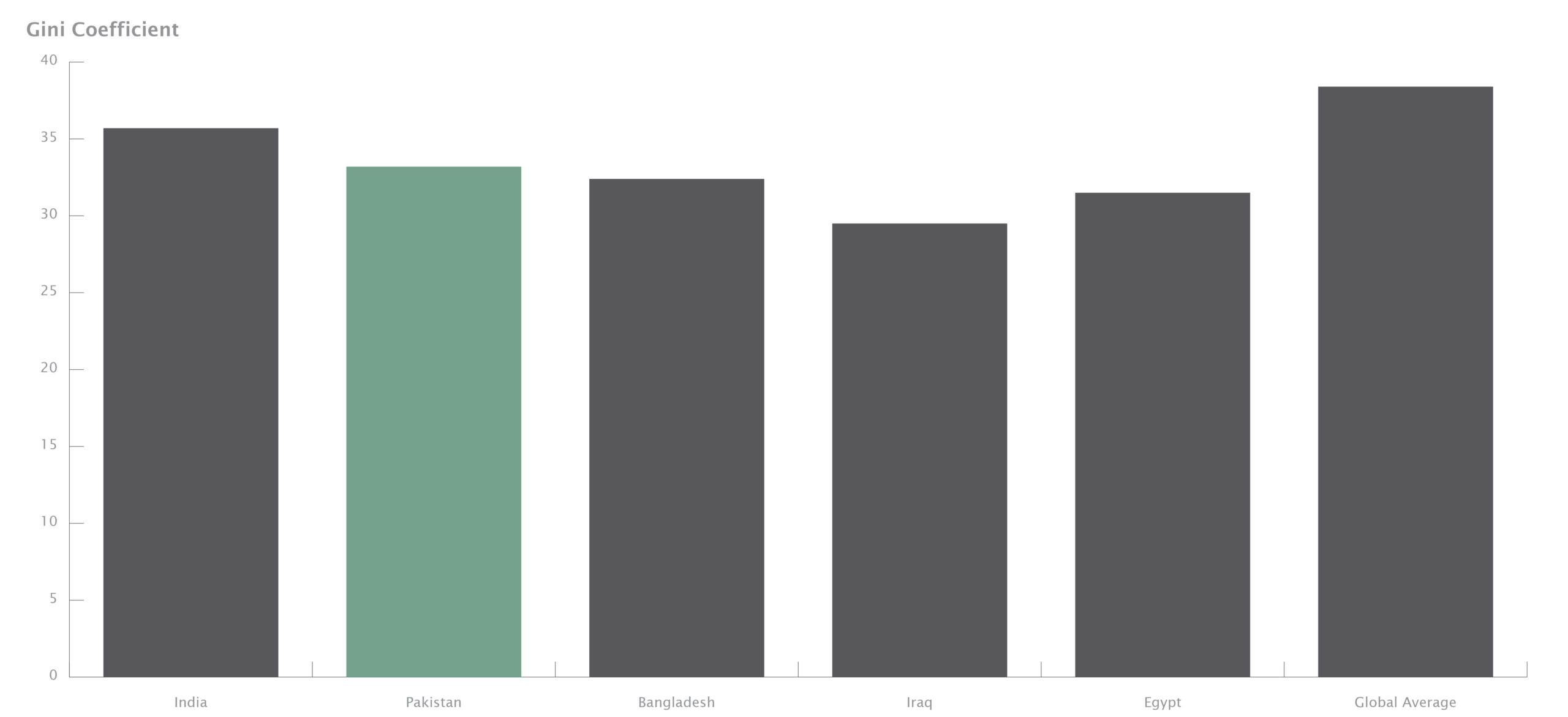

Besides suffering from low rates of saving, Pakistan is also one of the most unequal countries in the world. 2020’s Gini coefficient, which measures the state of income inequality, where a high score denotes a greater inequality prevalence, ranked Pakistan as more unequal than Bangladesh, Egypt and Iraq.

Inequality in Pakistan is lower than the global average, but higher than countries such as Bangladesh and Egypt

Source: World Population Review; MP Analysis

This income inequality translates directly into savings inequality. While the figure for average monthly savings in Pakistan is PKR 4814, the minimum monthly amount saved in the country is negative PKR 316,110, with the maximum amount being PKR 15,05,404 (while calculating savings inequality, remittances were excluded) —an extremely high degree of variation.

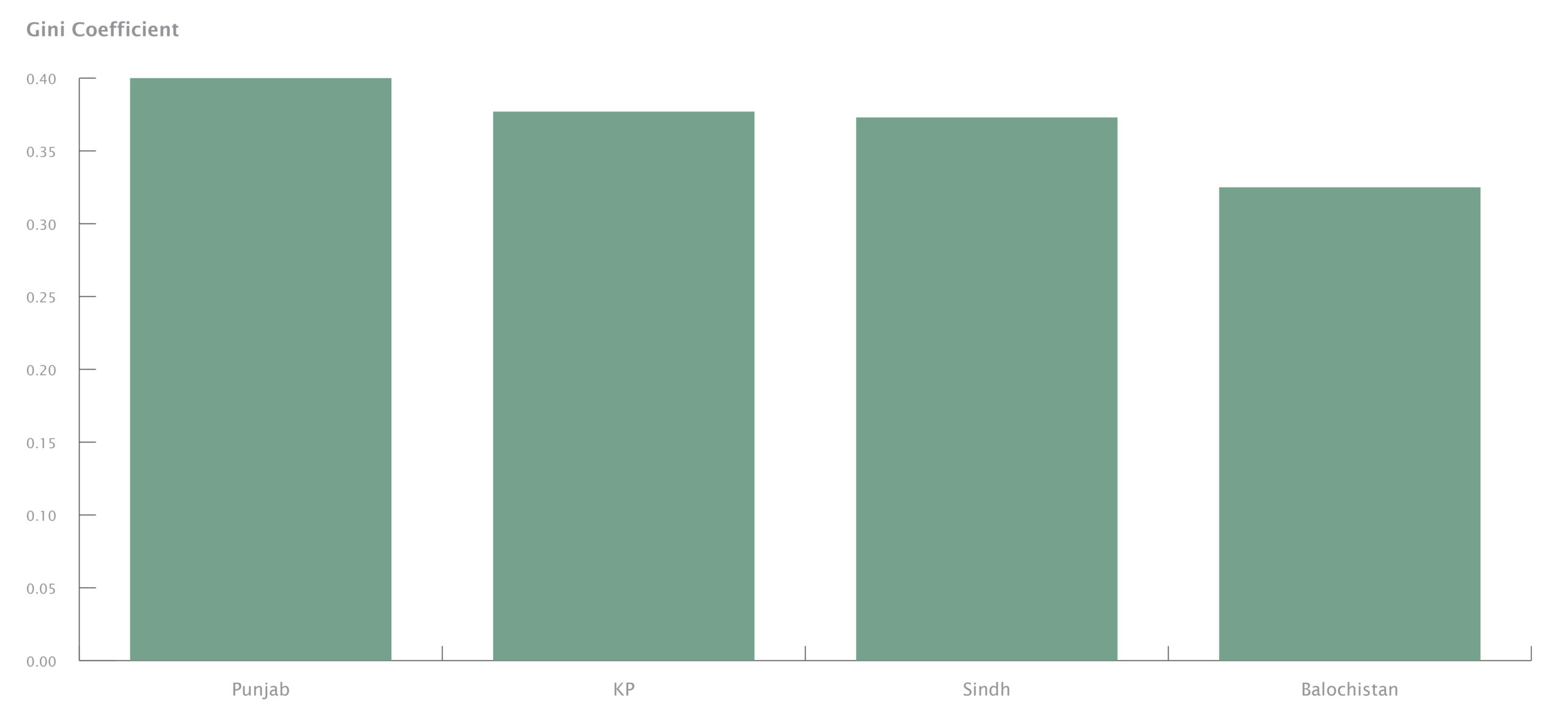

Going one level deeper, data from PSLM Survey of 19-20 tells us that Punjab is the most unequal province with a Gini coefficient index of 0.40, as compared the country’s average of 0.33. Sindh and Khyber Pakhtunkhwa are tied at 0.37, while Baluchistan was the least unequal province with a Gini score of 0.32.

Provincial-level breakdown of Pakistan’s Gini coefficient shows Punjab leading the way in savings inequality

Source: PSLM; MP Analysis

With Punjab leading the way in income inequality, it is no surprise that the province is also in the lead when it comes to savings inequality, ranking above KP, Sindh and Baluchistan.

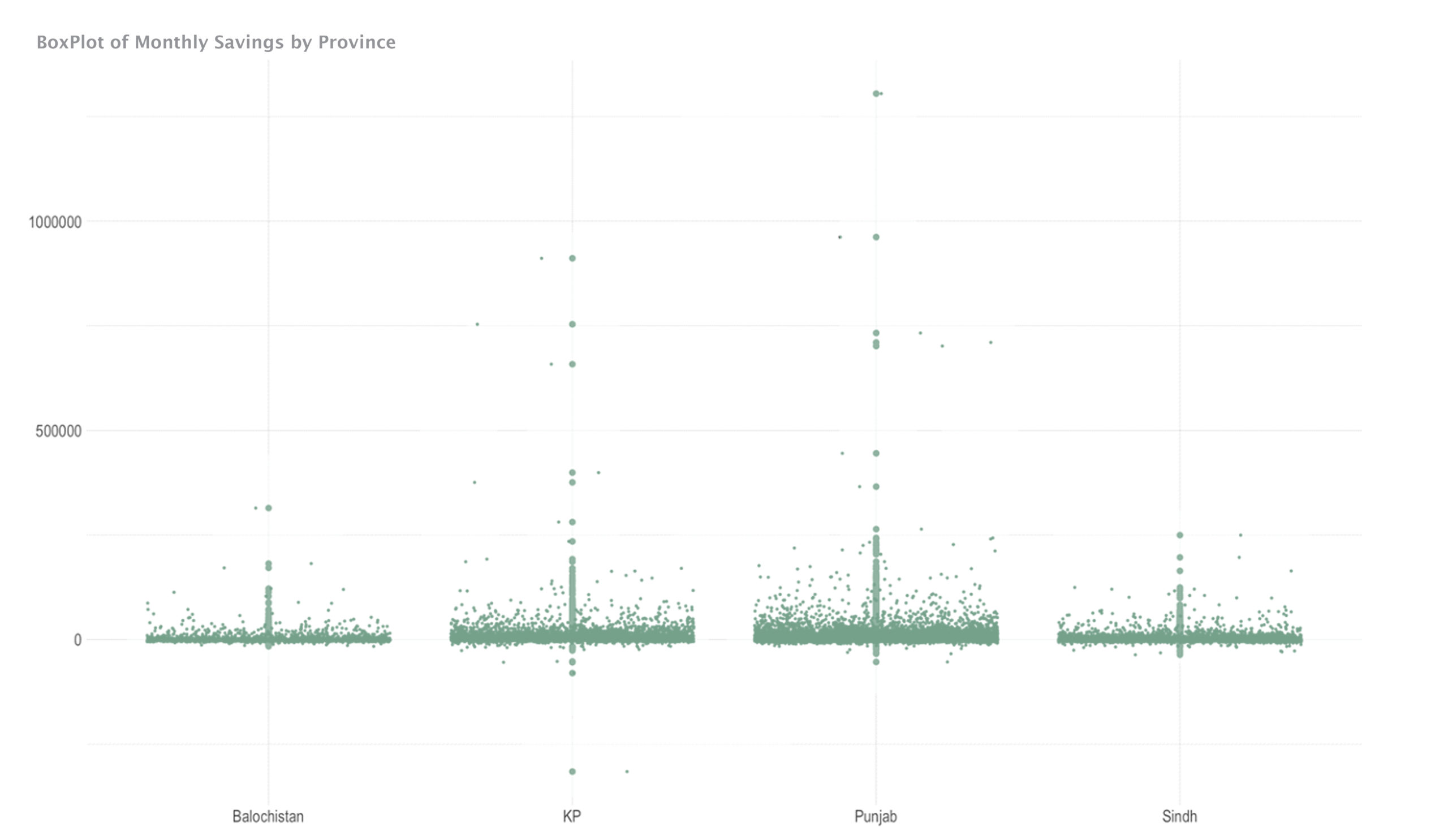

Provincial breakdown of monthly savings demonstrates that a majority of the individuals in all four provinces save less than 250k, with most the populations’ savings hovering between 10 to 50k per month. The data also reveals that maximum amount of monthly savings does not go beyond 1000k in all provinces, whereas, in Punjab, several individuals are found to be saving well and above 1500k per month.

Source: PSLM

Inequality in the Land of the Five Rivers

The range of savings vary widely in Punjab, with the bottom 25% having an average negative savings of PKR 1284, whereas the top 25% of the population having an average monthly savings of PKR 70,725, a difference of PKR 72,099 between the two quintiles.

A further breakdown of the largest province into rural and urban regions reveal further inequality in savings rates, with the bottom 25% of the urban population having an average negative savings of PKR 1898, whereas the top 25% having an average savings of PKR 96,727, a difference of PKR 94,829. Rural Punjab is somewhat less unequal with the difference between the bottom and top 25% being PKR 60,867.

What about the rest of the country?

According to the data, KP ranks second when it comes to income and savings inequality, with the bottom 25% having an average negative savings of PKR 932, whereas the top 25% having an average monthly savings of PKR 77,625. When it comes to urban-rural savings inequality, urban KP was found to be more unequal than rural KP, as was the case in Punjab.

Baluchistan, despite ranking the lowest on income inequality, had a savings difference of PKR 46,898 between the top and bottom 25% of the population, higher than Sindh’s PKR 43,040, which may be due to overall lower incomes in Baluchistan. However, Baluchistan’s numbers should still be read with caution due to the vast number of people residing in rural and remote areas (more than 55%), because of which it can be difficult to obtain reliable data on either income or savings.

Overall, the trend of high levels of savings inequality persisted across all provinces. The question arises as to why does the top 25% save more than the rest of the quintiles? A generalized reason could be the higher than national average incomes of such segments of the population and the top 25% of the segment utilizes available domestic financial services to the fullest. The bottom half of the population are unbale to completely employ financial services and instruments primarily because of lack of information asymmetry and cultural constraints. Socio-cultural limitations are being faced by the majority of the populace of Pakistan, especially those residing in rural areas. Being a predominantly Muslim country, social norms against interest-based borrowings and savings alike self-exclude the poorest of the poor. Despite efforts being made by involved state stakeholders such as SBP and NGOs such as Akhuwat and Kashf Foundation to bank the unbanked, the rate of financial inclusion has been slow relative to regional peers. As of 2021, the financial rate stands between 17-20% of the total population. Financial exclusion rate amongst Muslim farmers having access to microloans, is approximately 40% and most of them cite religious reasons for not opening a savings bank account and borrowing interest-based microloans. Thus, if the goal is channelizing the savings of the bottom 25% of the population, it is imperative for the stakeholders involved to undertake pro-active reforms in the domain of financial inclusion.

What is to be done?

For Pakistan to adopt a path of investment-induced sustainable economic growth, it is necessary that the country take drastic measures to increase the domestic savings rate. Only then can it break the over-dependence on external sources of finance such as FDI, remittances and debt. Several recommendations based on evidence-based policy frameworks can be taken by the government to enhance savings through financial inclusion initiatives such as:

- Initiate informative and educational marketing campaigns and features that try to overcome socio-cultural obstacles to open savings accounts.

- Provide access to low-cost savings accounts especially in rural areas.

- Collaborate with microfinance organizations to introduce shariah-compliant saving instruments and make use of their vast distribution networks.

- Undertake contextual technological innovations, including expansion of mobile banking platforms such as EasyPaisa and include features such as direct deposit facilities.

- Encourage and provide financial and non-financial support to fintech based startups.

The list of recommendations is by no means, an exhaustive one but includes some of the fundamental and key steps to be undertaken to enhance domestic savings.