Central to a discussion on the economic prospects of the country is the relationship between the IMF and Pakistan. Now that we have completed a broad understanding of Pakistan’s structural economic issues, we can move on to discussing its long-term plans. Since 1958, there have been 22 agreements between the IMF and Pakistan and hence it is important to include the multilateral institution when discussing the country’s plans. That is not to say that the only plans Pakistan has are those with the IMF. In fact, Pakistan’s Ministry of Planning Development & Special Initiatives publishes regular annual plans and has several policy papers highlighting what needs to be done to address structural issues.

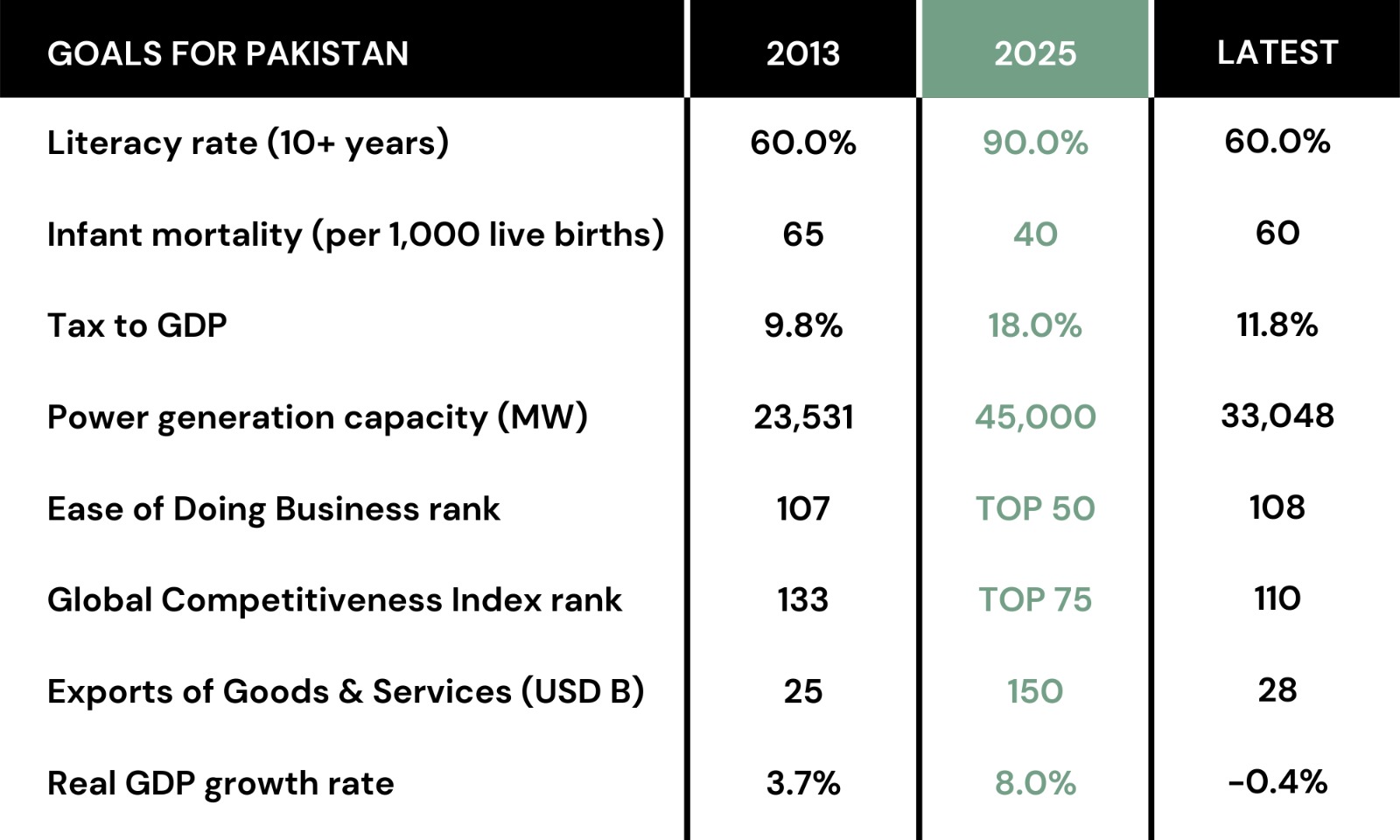

In early 2014, the ministry also published a Vision 2025. This was an economic charter of sorts, which laid out the long-term plan aimed at making Pakistan one of the top 25 global economies. The plan highlighted several of the same issues that Macro Pakistani has discussed and set clear targets for the country to achieve by the year 2025.

Pakistan had a vision

Selected indicators from Pakistan’s Vision 2025

The government in charge of creating Vision 2025 was PML-N but by the end of their 5-year term in 2018, they had not made any significant progress toward achieving set targets. Even after the arrival of the new PTI government, Pakistan continues to fall short of those hefty goals. Assuming linear progress, almost 60% of the goals should have been met by 2020, 7 years on from when the plan was envisioned. Let’s summarize the progress to date:

- Primary focus was on developing human and social capital. Literacy should have been at 77.5% by now but is still at the same level it was at in 2013. Health outcomes have not improved significantly either – infant mortality is at 60 instead of 50 deaths per 1,000 live births at present.

- To achieve inclusive growth, tax collection was supposed to be at 14.5% of GDP but is trailing at 11.8% for now. Energy issues were supposed to be resolved with affordable electricity provided to over 90% of the population. While power generation has improved significantly, electricity prices in Pakistan are still the highest in the region.

- Pakistan was supposed to become a competitive knowledge economy, but has only made limited progress in competitiveness and become worse at Ease of Doing Business since 2013.

- As a result, the 6x increase in exports that was envisioned as part of greater regional connectivity initiative, has not come about. Pakistan’s exports of goods and services, stood at USD 28 billion in 2020 compared to the level of almost USD 100 billion, they should have been at by now.

We like to take things slow

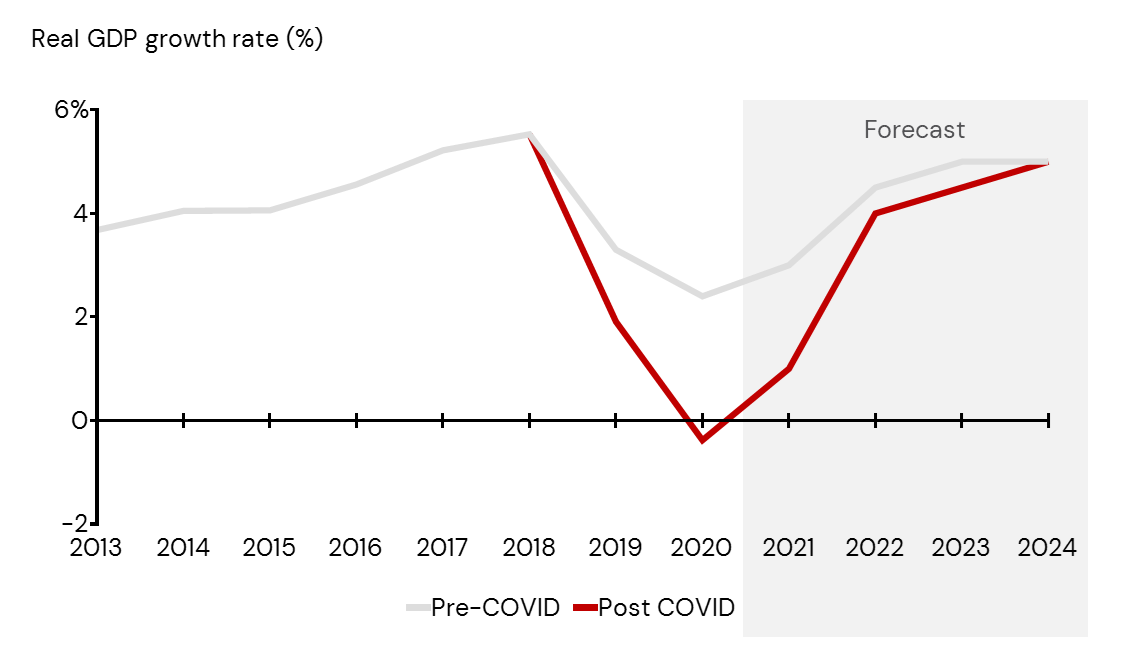

In order to achieve Vision 2025, real GDP growth of up to 8% was required. The plan was pretty simple and included all the features Macro Pakistani also believes to be critical for growth. Invest in human development, boost public revenues to invest in the domestic economy, empower businesses and improve competitiveness to achieve export-led growth. However, failure to address structural issues has led the country to consistently fall short of growth targets.

Pakistan’s real economic growth (2013-2024)

Some might look at the above chart and think that Pakistan was on a steady growth track until 2018, when it had 5.5% of real GDP growth. If similar trends had continued, Pakistan’s real economy would in fact be growing at 8% by 2025. So let’s understand why this is not true and how this growth was not sustainable. Human capital development metrics were still abysmal in 2018. Tax collection was half of full potential. Investment levels were well below regional benchmarks and predominantly fueled by foreign savings. Hence, labor, capital and total factor productivity growth was stagnant and the country was on its way to de-industrialization. Pakistan was attempting to (once again) achieve export-led growth, without improving innovation and competitiveness.

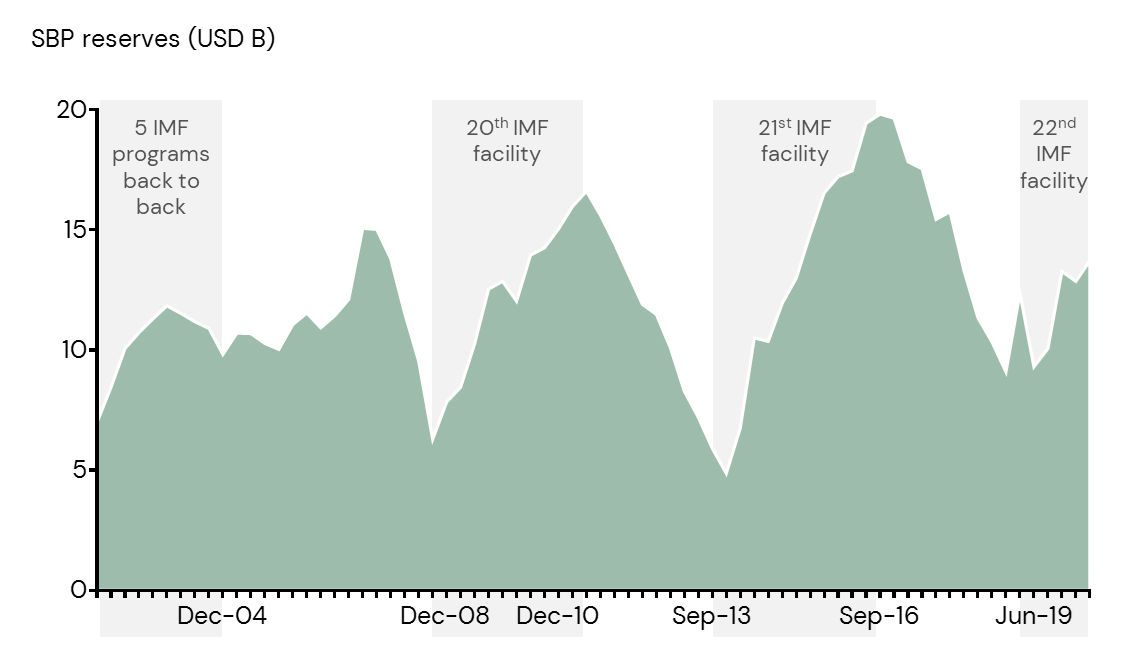

We love the IMF

Instead, what Pakistan ended up achieving was consumption-led growth. The current account deficit jumped to over 6% of GDP as consumption of imports increased rapidly and the country found itself in a balance of payments crisis. This was nothing new and this cycle has repeated itself several times in Pakistan’s history.

SBP foreign exchange reserves and IMF interventions (Sep ’02 – Jun ‘20)

When there is a balance of payments crisis, the State Bank of Pakistan is forced to use up foreign exchange reserves to finance deficits. When reserves reach critically low levels, the IMF and Pakistan enter into agreements and hope things turn around. Without delving too much into the history of the relationship between the IMF and Pakistan, Macro Pakistani readers should understand that the International Monetary Fund regularly hands out rescue packages to Pakistan with strict austerity measures geared towards stabilization. Rather than reading official annual plans by the government, one should read IMF reports to get a sense of where the country is headed.

Readers should also note that Pakistan also rarely completes these programs. In fact, the last one ending in 2016, was the first bailout package that reached a full conclusion. Previously, governments used to find the requested measures too difficult to implement or just failed at achieving them. Until December 2004, the IMF and Pakistan entered five back-to-back programs since September 1993. When the next crisis hit in 2008, a 3 year Standby Arrangement was agreed between the IMF and Pakistan. Reserves started to drop again and fell to less than USD 5 billion in 2013 after which another agreement was reached. After the completion of that program, reserves fell again to around USD 9 billion by June 2019, bringing in the 22nd IMF agreement since 1958.

Stabilization not growth

It is important to note that these agreements between the IMF and Pakistan are not meant for growth. They are programs aimed at macroeconomic stability and fixing external and internal imbalances within the country. The latest program as well, was expected to address the twin deficit issue of fiscal and current account deficits.

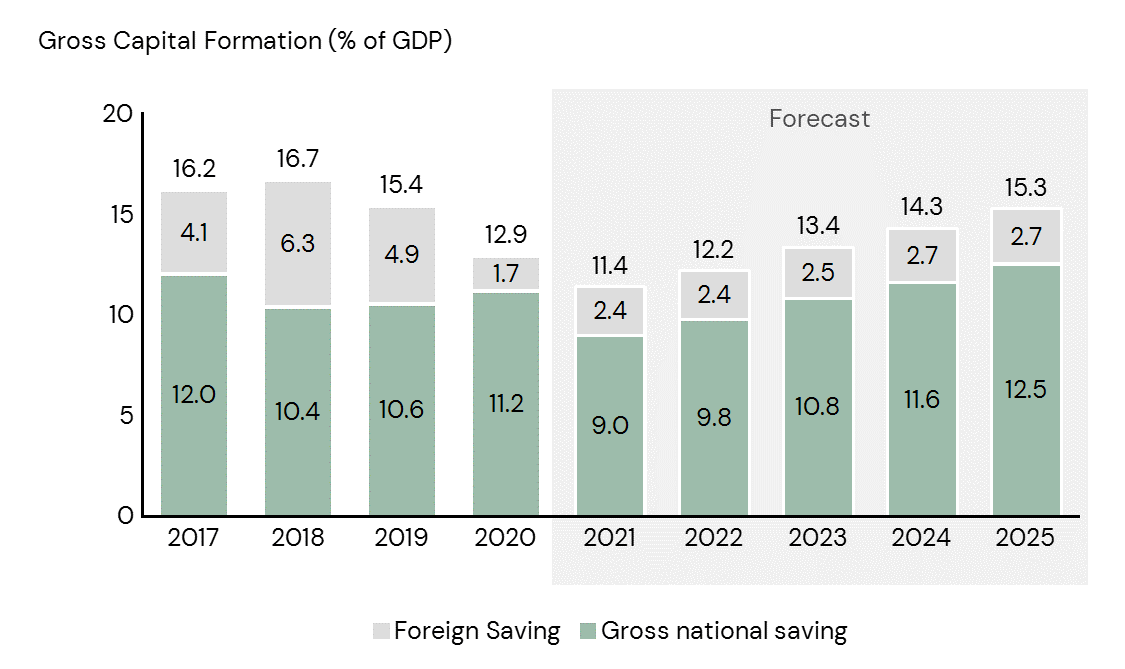

Contribution of saving to investment in Pakistan (2017-2025)

Take for example the structural issue of investment in Pakistan that Macro Pakistani identified earlier. Historically, Pakistan has invested around 15% of its GDP compared to over 30% of GDP by countries like Bangladesh, India and Indonesia. Even with the IMF program, it is not the level of investment that is expected to rise. It is the make-up of that investment – a move away from reliance on foreign saving to focus on domestic national saving by both the private and public sectors. While in 2018, 6.3% of GDP or 38% of total was invested from foreign savings (essentially the current account deficit), only 2.7% of GDP or 18% of total is expected to be invested from the same sources.

If you are curious to learn more about the program, read the full report published post COVID-19 here. The existing program was paused due to the Great Lockdown and a separate facility to assist with the pandemic worth USD 1.4 billion was disbursed. As part of the original program, Pakistan was expected to raise government revenues to almost 20% of GDP, and reduce its fiscal deficit to 2.5% of GDP. Expenditures were expected to be moderated but with a higher focus on development spending, social support, health and education.

More of the same

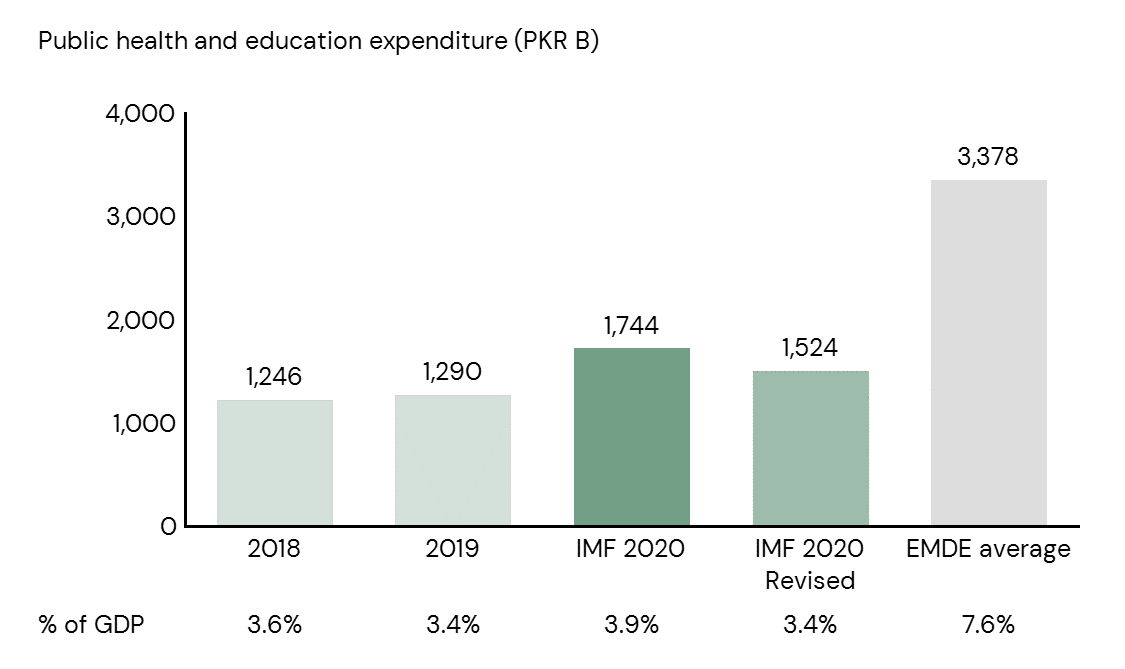

Targets were agreed between the IMF and Pakistan to bring the country in line with other emerging markets in terms of social spending. However, even before the pandemic, these targets were being revised downward as the IMF realized that the Pakistani authorities did not have the capacity required to make these expenditures.

Revision of indicative spending targets between IMF and Pakistan

Just like Vision 2025, the IMF program also had a focus on human development spending. Initially, the target for public health and education spend was set at PKR 1.7 trillion for 2020, a 35% increase from 2019. After just one quarter, when the authorities missed the quarterly target by 26%, the annual target was revised downward to PKR 1.5 trillion, more in line with historical spends of 3.4% of GDP. The goals for public health and education expenditure were part of IMF’s Indicative Targets (IT) list, which also included cash transfers (BISP), FBR tax revenues, refund of tax arrears and circular debt elimination. If Pakistan misses these targets, nothing really happens.

However, if Pakistan misses any Quantitative Performance Criteria (QPC), which include targets for SBP reserves and government primary deficits, a waiver from the IMF Executive Board would be required. Otherwise the program would be cancelled. Fortunately, until the last review in December 2019 before the pandemic, Pakistan met all the QPCs and the economic reform program was on track. Things changed after pandemic hit and the Great Lockdown was instituted. Next time we will discuss how the government responded in fiscal and monetary terms to address the impact of COVID-19 on Pakistan.

Hope your view of 2025 statistics comes true ,it’s really encouraging n we hope for the best for Pakistan.

through this viewage we are going through. We cant succeed. this statistics is normally fictionally based but the way Pakistan is going through

is so critical in situations.

Beneficial material. Kudos!

https://essaywritingservicelinked.com/ make a research paper

Perfectly voiced genuinely. !