Last part of the Macro Pakistani series on structural issues brings us to trade in Pakistan. We started with explaining the CIGXM of Pakistan’s economy, which mentioned exports and imports. Most people are familiar with trade and read a lot about the current account deficit. Some have even heard of the balance of payments crisis but might not fully grasp the details. Hence, before talking about trade in Pakistan, let’s make some economic terms clear for all readers.

We need balance

In order to trade in this globalized world, a country needs to be able to exchange currency with others. The amount of incoming dollars it has, at least needs to equal the amount outgoing. Apart from the US, no other country in the world can print the US dollar, which is the dominant global currency. Because Pakistan has historically been unable to attract enough dollars, it needs to rely on borrowing from the rest of the world.

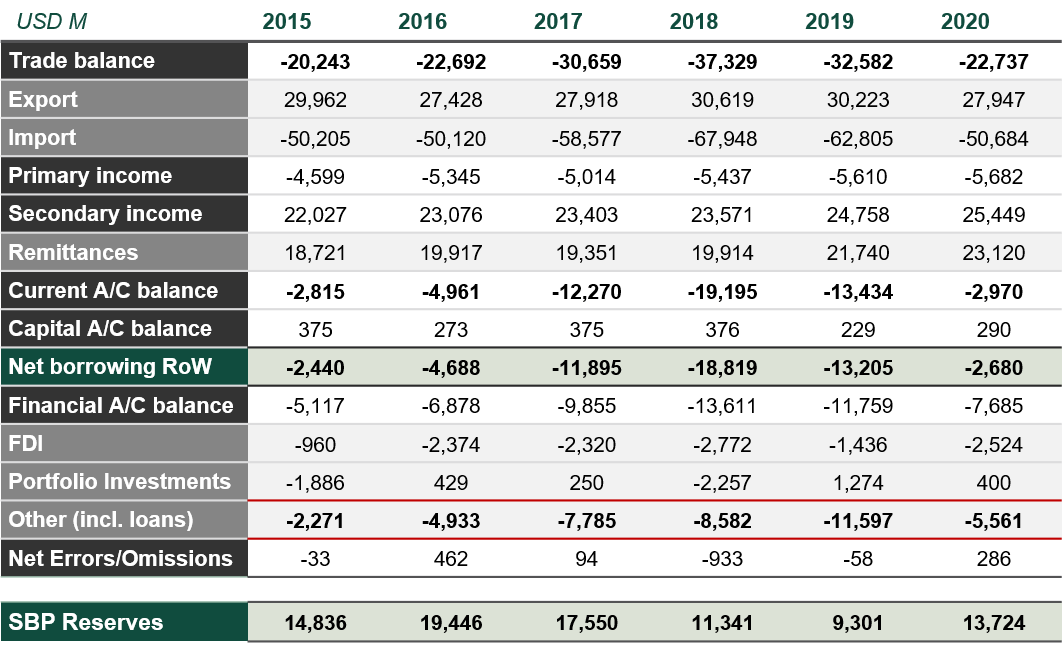

Balance of Payments in Pakistan 2015-20

The balance of payments has current account and capital account on one side and financial account on the other. Both sides are denominated in dollars and need to balance each other out. First, within current account, there is the trade balance: exports minus imports of goods and services, which most are familiar with. Similarly, there is the primary income balance, which mostly consists of repatriated profits. For Pakistan, this is usually a negative because we repatriate more profits than we bring in. Then there is the secondary income balance, which includes one-sided transfers like remittances. These are the saving grace of Pakistan since the current account would be in significantly worse shape without them.

In 2020, exports of goods and services were roughly USD 28 billion while imports were over USD 50 billion. Including primary income, the deficit would be USD 28 billion. It is only with secondary income (with over USD 23 billion of remittances) that we manage to reduce our need for outside funding. The other sources of funding, which come through the financial account are Foreign Direct Investment (FDI), portfolio investments in equities or debt and foreign loans. If these aren’t enough, the State Bank has to resort to using up its reserves which are kept for rainy days.

Devaluation is good

As highlighted in the last chart, Pakistan’s balance of payments was sustained by foreign loans in the past, which have only recently decreased after devaluation. Each time the country was undergoing a balance of payments crisis, it would ask either ‘friendly’ countries or the IMF for loans. Apart from the structural issues we have already discussed at Macro Pakistani, a primary driver of Pakistan’s current account woes was its overvalued exchange rate.

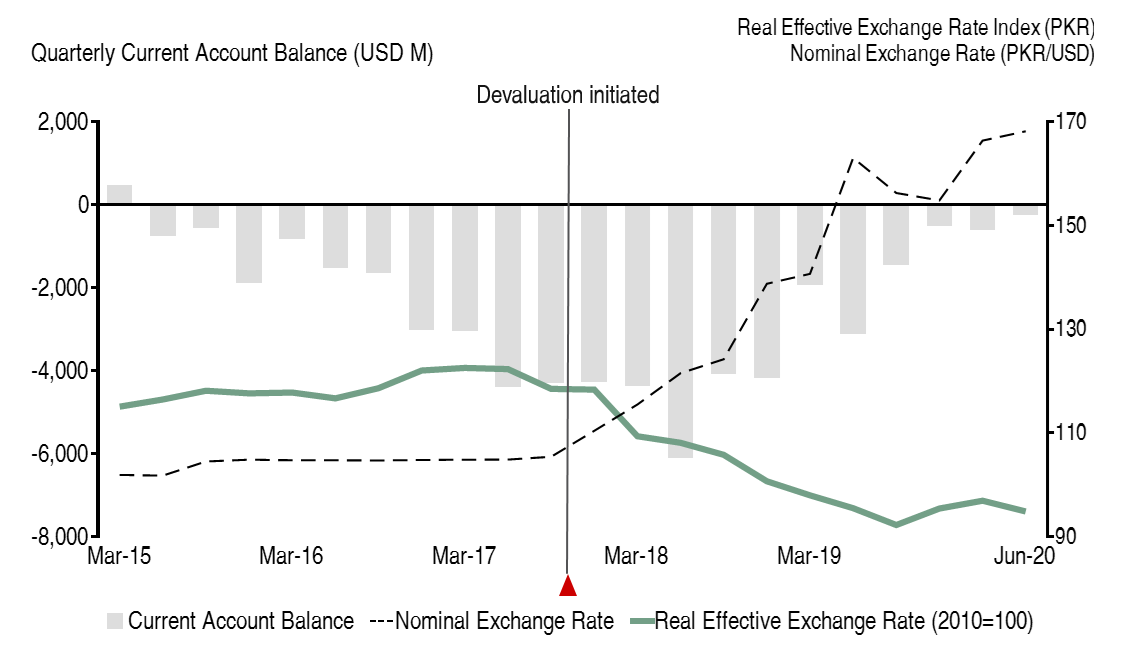

Relationship of current account deficit and exchange rates 2015-20

The dotted line (Nominal Exchange Rate) in the chart shows how the currency was fixed at 100 PKR/USD for several years while the green line (Real Effective Exchange Rate) was rising. When countries trade with others, they consider the value of the currency of their trading partner, in relation to the value of other currencies, adjusted for inflation. To understand this and its impact on trade in Pakistan, let’s return to thinking like an exporter.

We have discussed before how Pakistani exporters are at a disadvantage to those in Bangladesh due to high energy prices. Now let’s add to that the complexity of exchange rates. A shirt costs PKR 100 to produce in Pakistan and BDT 100 in Bangladesh and both equal USD 1 in dollar terms. Due to lack of investment and inflationary pressures, the cost of the Pakistani shirt rises to PKR 110 or USD 1.1. Export orders shift from Pakistan to Bangladesh since it’s cheaper to procure shirts from there. But that would happen if Pakistan kept the exchange rate parity at 100 PKR/USD. If the market was allowed to dictate the price, as soon as Pakistani goods would become less competitive, the demand for its currency would also fall and absorb the price differential.

Let’s get real again

Instead of the dollar price of the shirt increasing, if the parity changed from 100 PKR/USD to 110 PKR/USD, the dollar price of the shirt would be USD 1 and export orders would return to Pakistan. When you let the currency devalue, two things happen. First, exports become relatively cheaper and the country’s goods and services become more competitive with the rest of the world. Next, imports become relatively expensive and other countries’ goods and services become less attractive. As the above chart shows, the current account becomes worse before it becomes better. But as the below chart shows, it does become better.

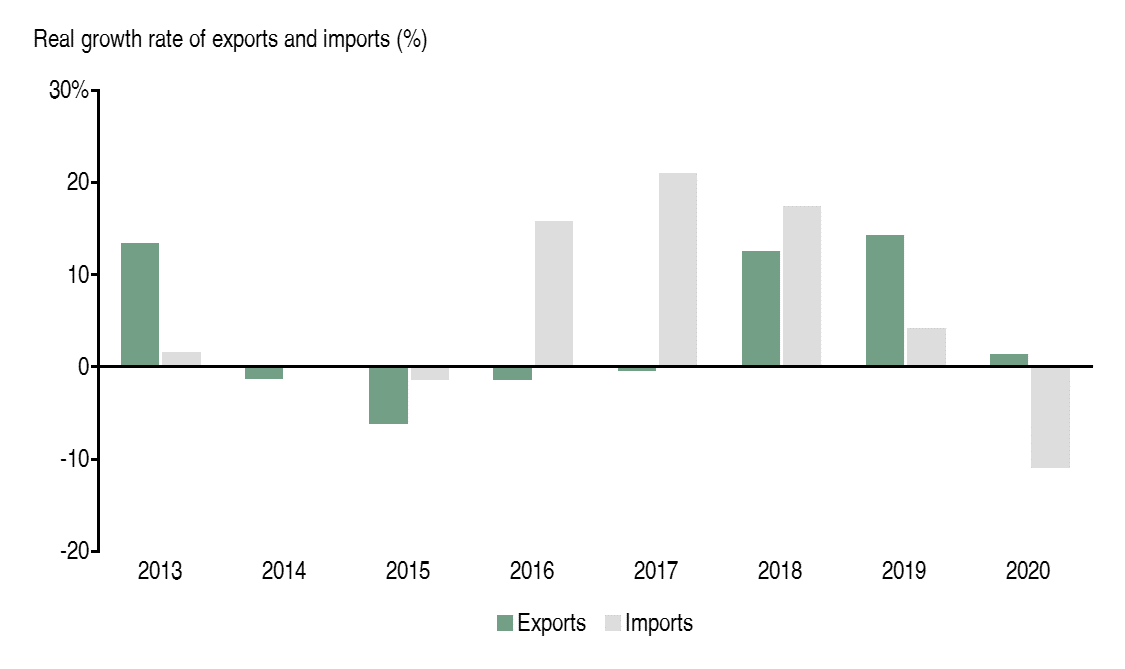

Real change in annual export/import of goods in Pakistan 2013-20

When exports become more competitive, their volume increases. People buy more shirts but at a lower price. Hence, the total value only increases after a period of time. Similarly, when imports become less attractive, their volume decreases. But people are forced to buy them at a higher price for a period of time. In the case of Pakistan, the bulk of our import bill is related to oil, which has no substitutes. However, between 2018 and 2019, you will see Pakistani exports did increase and Pakistani imports did decrease in volume or real terms. In value terms, our exports fell slightly from USD 30.6 billion in 2018 to USD 30.2 billion in 2019. Imports on the other hand, fell significantly, from USD 67.9 billion to USD 62.8 billion.

In 2020, this trend continued. While the growth rate of exports fell sharply due to COVID-19 in the last quarter, imports fell even faster and the current account deficit decreased. In addition to the exchange rate, depressed demand in the economy along with low oil prices also helped reduce imports.

Manufacturing is a problem

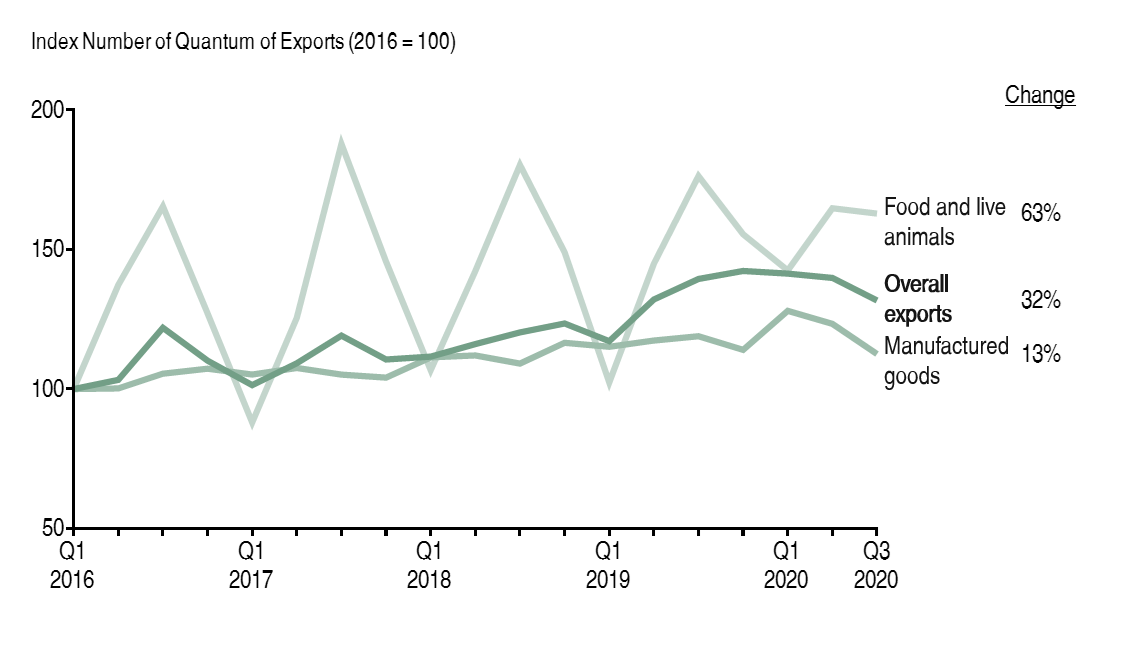

This improvement in current account balance was the silver lining of the Great Lockdown we discussed in an earlier article. With a market based exchange rate, like the one Pakistan has now, we can expect exchange rates to absorb shocks to the economy, rather than depleting the State Bank’s foreign exchange reserves. Even after switching from a fixed to a market based exchange rate, trade in Pakistan has not fully picked up. While overall exports are on the rise, manufacturing is still lagging behind as other structural issues remain unaddressed. Since 2016, the quantum of overall exports has increased by 32% while manufacturing has only increased by 13%.

Real change in quarterly export of goods in Pakistan 2016-20

Competitive exchange rates do not automatically translate to competitive goods and services. Pakistan ranks 110th out of 141 countries included by the World Economic Forum in their Global Competitiveness Report 2019. Other regional peers like India (68th), Sri Lanka (84th) and Bangladesh (105th), are all ranked higher. Trade in Pakistan cannot improve significantly until the country becomes more competitive. According to the report, Pakistan is similar to other South Asian countries in having poor institutions and infrastructure, macroeconomic instability and lack of innovation capability. Where it significantly lags behind is under the human capital metrics of health and skills, which we have also discussed earlier. It also ranked 131st out of 141 countries for ICT adoption, which shows how technology has a major role to play in the country’s economic future.

We need the US

In this globalized world, another factor that will play a role in boosting trade in Pakistan will be foreign relations. The map below shows Pakistan’s trade balance with individual countries. You can hover over any country to see key metrics like exports, imports and the share each country holds of Pakistan’s trade surplus/deficit.

Share of trade surplus/deficit of goods with Pakistan

Source: State Bank of Pakistan

What should be immediately visible is the two extreme countries. While the US (darkest green) contributes over 20% to Pakistan’s trade surplus, our deficit with China (darkest red) makes up 30% of the total trade deficit, which means we import a lot more from China than we export. In 2006, Pakistan and China signed a Free Trade Agreement (FTA), which gave each country certain preferential treatments. The aim was to improve bilateral trade ties between the two countries. According to the Pakistan Business Council, while trade between the two countries increased by 242%, between 2007 and 2018, Pakistani exports to China increased by 196% while imports from China increased by 249%. This meant the FTA favored China more than Pakistan. Business groups routinely claim the agreement was poorly negotiated and that Chinese goods inundating the Pakistani market contributed to premature deindustrialization.

Pak Cheen Dosti

A new deal between the two countries has been signed and most observers are hopeful. Relative to the first agreement, the new FTA offers substantial improvements in Pakistan’s tariff access to China. In order to boost trade in Pakistan, the country will need to compete with China’s other trading partners to gain a larger share of its USD 2 trillion import market. However, the recent US-China tensions also offer an opportunity for Pakistan.

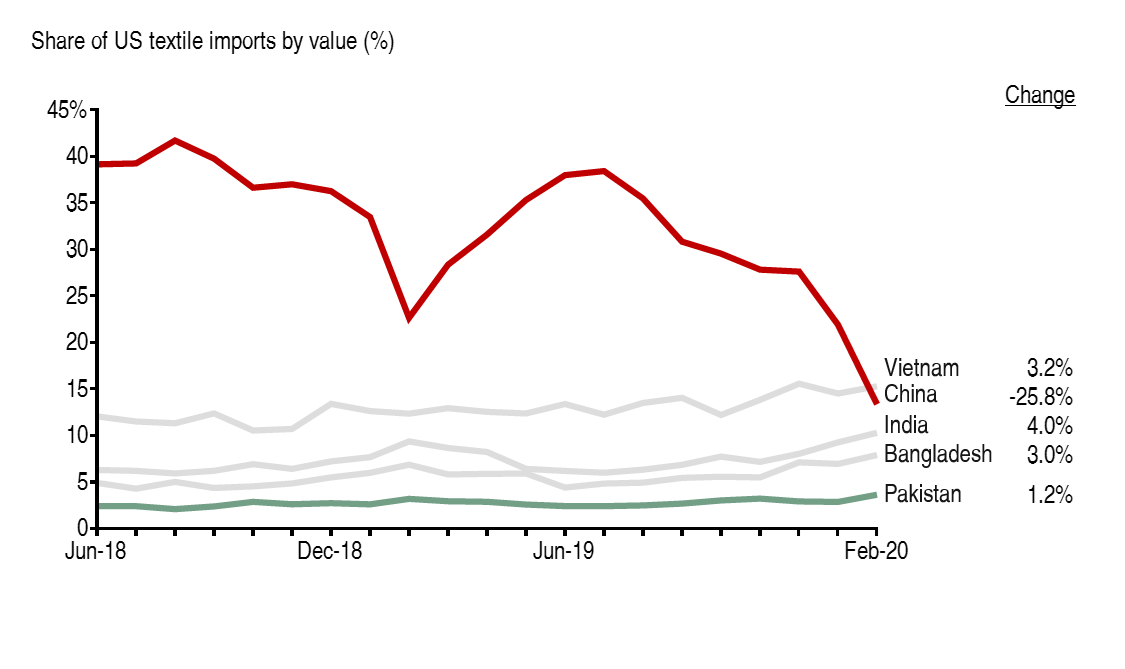

Share of US import of textiles of Pakistan vs. regional peers 2018-20

Since June 2018, political tensions have led to US significantly reducing trade with China. From a high of over 40% share of US textile imports, China was down to less than 15% share before the pandemic. This reduction of 25 ppts in share was absorbed by countries like India (4 ppts), Vietnam (3.2 ppts) and Bangladesh (3.0 ppts). Pakistan has managed to increase its share of US textile imports by only 1.2 ppts, even lower than Cambodia (1.7 ppts). There is room to capitalize on the US-China decoupling, especially within textiles: a sector where Pakistan and Bangladesh have similar levels of access in the US.

Pakistan needs to carefully assess its foreign geo-political ties and negotiate market access accordingly. It already enjoys preferential trade access within the EU, under the GSP+ scheme. However, it suffers from high duties in other developed countries like Japan, Canada and Australia. Regional trade is also limited, with SAARC countries representing less than 3% of total trade in Pakistan. Having completed a broad understanding of Pakistan’s structural economic issues, we will next see how the country has performed compared to its communicated plans.

Good job Faiz ahmed. How we can connect, for further discussion on other indicators.