One of the best-performing commodities at the moment is carbon dioxide (CO₂). At the beginning of 2018, the price of European emission rights, the right to emit one ton of CO₂, was around EUR 6. A year later, the price was at EUR 25, while currently it is being traded at EUR 80. On the other hand, carbon credits, which can be exchanged for emission allowances under certain conditions, have long been traded for less than EUR 30 cents. What is the difference between these tradable tons of CO₂, and why is there such a significant disparity in price?

Types of emission allowances

It is first important to understand that there is a difference between rights to emit CO₂ (emission allowances) and rights to claim already reduced CO₂ (carbon credits). In addition, these need to be placed in the context of international climate agreements that ultimately laid the foundation for the lively trade in greenhouse gases.

International framework

Following the reports of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC), the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) was established in 1992. The aim of this climate convention was: “to stabilize the concentration of greenhouse gases in the atmosphere to such a level that a dangerous human influence on the climate is prevented”. This treaty has since been signed by 197 countries. Each year all countries meet at the Conference of the Parties (COP) to discuss the progress and ambition with regard to climate change.

The Kyoto Protocol was signed at the third COP in 1997. The implementation of this treaty regulates greenhouse gas emissions from western industrialised countries, the so-called “Annex I countries”. The treaty finally entered into force in 2005 after sufficient countries had signed and ratified the treaty. All Annex I countries in the treaty were granted emission targets for a first period (2008-2012) and second period (2013-2020). For the second period, 37 parties committed themselves—the EU and its 28 member states, Australia, Belarus, Iceland, Kazakhstan, Liechtenstein, Norway, Switzerland and Ukraine. The United States, Canada, Japan, Russia and New Zealand made no commitment for the second period, and China and India also had no obligations within the Kyoto Protocol.

The treaty was enforced by allocating allowances for each period, Assigned Amount Units (AAUs). One AAU stands for the right to emit 1 ton of CO₂e (CO₂ or equivalent greenhouse gas) during that period. Part of the protocol was that these rights may be traded, one of the so-called flexible mechanisms. Countries that need fewer AAUs than allocated can sell AAUs to countries that need more.

Development of Emissions Trading Systems

Since the start of the second period, this international emissions trading has only been used to a very limited extent. Instead, we see emissions trading mainly taking place at regional, national or local level. By far the largest emissions trading system in the world is the European Union Emission Trading System (EU ETS) that has existed since 2005. The EU ETS must ensure that the European Kyoto targets are met: 20% reduction of greenhouse gases in 2020 compared to the level in 1990. The EU ETS regulates emissions from around 11,000 companies in the energy sector, industry and aviation (45% of total emissions in the EU). For the other sectors, each European country is individually responsible for achieving climate goals.

Emission allowances within the EU ETS, European Union Allowances (EUAs), are partly allocated to companies. Companies that emit more must purchase EUAs. The total number of allowances is being phased down, so that the total emissions are reduced. Allowances are traded through an auction system and sold to the highest bidder. If a company cannot provide enough emission allowances, a fine will follow.

The idea behind this system is that, due to market mechanisms, reduction measures take place where they are most cost-efficient. Because there is supply and demand in emission allowances, CO₂ emissions get a price. Companies make their own decisions on the cheapest options: purchase emission allowances or take emission-reducing measures. Other such “cap and trade” systems are found in South Korea, California and Canada, among others. Countries such as China and Colombia are also working on the implementation of their own ETS system, with more countries expected to follow.

Price fluctuations in the EU ETS

In the early years of the EU ETS (2005-2008) the price of the EUA was between EUR 20 and EUR 30. From 2008, when the economic crisis started, prices fell to under EUR 10. Due to reduced economic activity, there was a surplus of emission allowances. Because these allowances can be saved, this also had an effect in the years following the crisis. The ETS faced considerable criticism, because the low price of the EUA would not motivate companies enough to emit less CO₂.

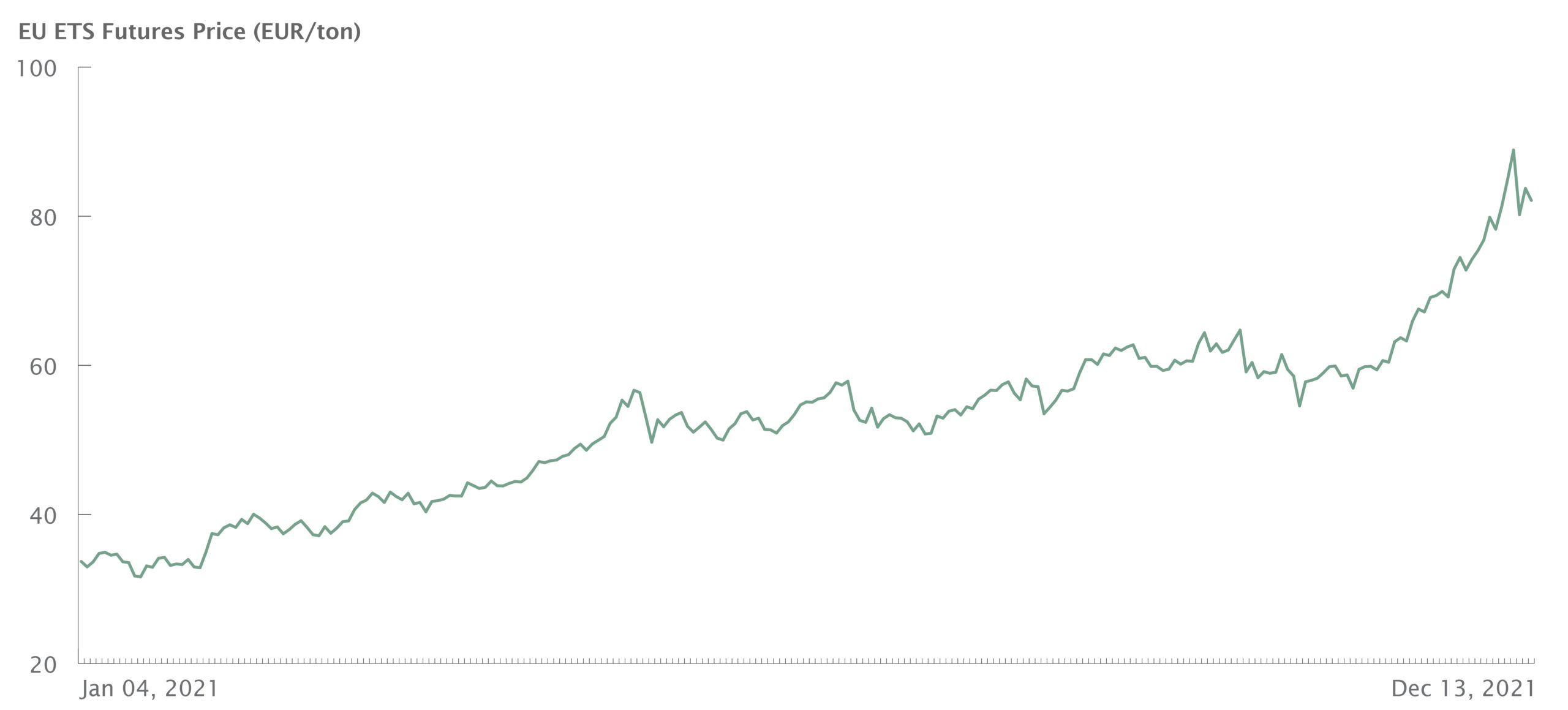

However, in 2018 there was a change in the price of the EUA. The improved economic climate, and especially the withdrawal of a surplus of allowances by the EU (market stability reserve), has led to this change. Due to the rising demand for emission allowances and the limitation of supply, we saw a sharp rise in the price of the EUA in 2018. In 2019, the price of the EUA increased to EUR 25 and has been trending upwards since.

The market price of one ton of carbon emission allowance in the EU has more than doubled in 2021

Source: ICE/Ember, MP Analysis

Carbon credits

In addition to emissions trading, there is another flexible mechanism within the Kyoto Protocol, the Clean Development Mechanism (CDM). Within the CDM, countries with a reduction obligation may achieve part of their target in non-Annex I countries. The idea behind this is that it is often more cost-efficient to achieve reductions in developing countries. One can think of projects in the field of renewable energy, reforestation, waste processing or energy saving. Every ton of carbon emission avoided within a CDM project results in a Certified Emission Reduction (CER). A CER gives the right within the Kyoto framework to claim a ton of CO₂e reduction achieved in a non-Annex I country, or in other words “to get credit for it”.

These carbon credits can be traded just like emission allowances. CERs can be used up to a certain maximum, 2% for most countries, to meet the Kyoto obligations. They can also be bought by companies or organisations. Within the EU ETS, these credits may be used instead of EUAs until 2020, under a number of strict conditions and up to a maximum. When a CER is used, it is cancelled in the CDM register (retirement) and can no longer be traded.

Pricing Carbon credits

CERs initially underwent a similar price development to European emission allowances. Like the EUA, CERs were in free fall after the 2008 crisis. But while the EUA has since recovered, it became clear in 2011 that CERs could only be used to a limited extent in phase 3 (2013-2020) of the EU ETS. Because the EU ETS was always the largest buyer of CERs, this led to a large surplus, causing prices to fall further below EUR 1. As a result of these extremely low prices, CERs have faced criticism for not reflecting the actual costs of reducing a ton of CO₂.

The price of CERs remains low at present due to the huge supply, compared to demand. One factor that may lead to higher demand for CERs however is the CORSIA scheme in the international aviation sector. Adopted in 2019, the “Carbon Offsetting and Reduction Scheme for International Aviation” (CORSIA) may lead to the sector depending on carbon credits, thus increasing the demand for CERs.

At the same time, the supply for CERs may fall in the future. It was agreed in the Paris climate agreement that from 2020, all countries must make their contribution to the reduction of greenhouse gases. If it appears that emission reductions from offsetting projects are counted within the National Determined Contributions (NDCs) of the country where the project is located, it is no longer possible to sell the emission reductions as carbon credits to foreign buyers.

Conclusion

The pricing trends for carbon credits and emissions allowances may continue to vary in the future, but their importance is only likely to grow. Companies are striving for climate-neutral or even climate-positive business operations, while countries are looking to meet their obligations under the UN Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). In this context, climate targets in projects are set to become increasingly relevant.