A common perception that many of us held growing up was that human society is always making progress. Yes, sometimes that progress is slow, sometimes it does not keep pace with the advancements made by other previously-comparable countries, but society as a whole is still always moving forward. However, one look at Pakistan’s nutrition statistics illustrates just how inaccurate that perception really was.

Setting children up to fail

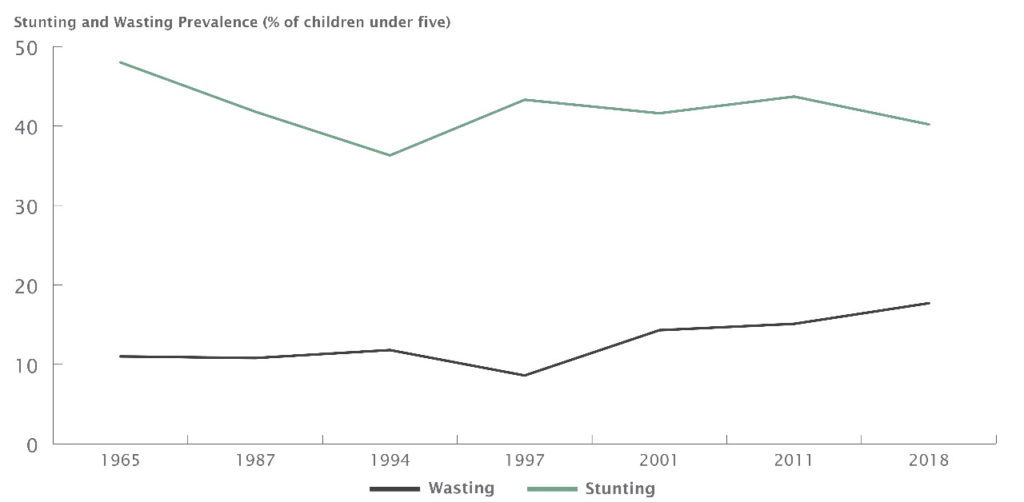

When it comes to the physical health and well-being of our children, we’re really still living in 1965. That was when the prevalence of stunting, a form of malnutrition that leads to low height for age, among children under-five was 48%. We made some progress in the subsequent decades, bringing the figure down to 36% by 1994. But since then, we’ve actually gone backwards. The most recent statistics tell us that, in the year 2018, 40% of children in Pakistan still suffer from stunting.

If you thought that was abysmal, then how about our statistics on wasting, another form of malnutrition that leads to low weight for height. In 1965, wasting in children under-five in West Pakistan was 11%. Incredibly, by 2018 that figure had regressed to 18%, a growth of 64% in the last half-century. To give some perspective on how far Pakistan lags behind the rest of the world, the global prevalence of stunting and wasting in children under-five is 21% and 7% respectively.

Childhood stunting (low height) has remained above 40% for the last 50 years. Wasting (low weight for height) among children under five has actually increased in that time.

Source: NNS 2018, MP Analysis

Dire nutrition statistics for children under-five aren’t restricted to stunting and wasting alone. 54% suffer from anaemia (up from 51% in 2001), 52% from a Vitamin A deficiency, 63% from a Vitamin D deficiency, and 19% suffer from a lack of zinc.

Struggling mothers

Focusing on children’s statistics alone doesn’t tell the full story. These numbers are a reflection of the malnutrition suffered by large sections of the adult population, and specifically the poor nutritional status of mothers. 14% of Pakistani women between the ages of 15-49 are undernourished, while 38% are overweight or obese—which, contrary to popular belief, is also a symptom of malnutrition. Breaking down their micronutrient deficiencies further, 42% are anaemic (against a global average of 33%), 80% have a Vitamin D deficiency, 27% have a Vitamin A deficiency, and 22% suffer from a lack of zinc.

Consequences of undernourishment

Lack of adequate nutrition has a very real effect on the daily lives of many Pakistanis. Malnutrition leads to lower muscle strength, greater likelihood of cardiorespiratory diseases, more risk of gastrointestinal illnesses such as diarrhea, lower overall immunity, and even heightened risk of anxiety and depression.

It also carries an economic cost. According to a study by the UN World Food Programme, child undernutrition costs Pakistan USD 7.6 billion annually, or approximately 3% of our GDP. To break that figure down further:

- USD 2.5 billion is the cost to the workforce from 180,000 children dying annually due to undernourishment

- USD 3.7 billion is the loss of future productivity due to cognitive and other deficits caused by stunting and anaemia in children

- USD 0.7 billion is the cost of work performance deficits among adults with anaemia

- USD 1 billion represents the expenses incurred in treating excess cases of low birthweight, diarrhea and respiratory diseases caused by zinc deficiency and maternal undernutrition

Cause of undernourishment: Food insecurity

Perhaps the single biggest driver of undernourishment in Pakistan is food insecurity. The UN’s Food and Agriculture Organisation describes food security as “access to sufficient, safe and nutritious food that meets their dietary needs and food preferences for an active and healthy life”.

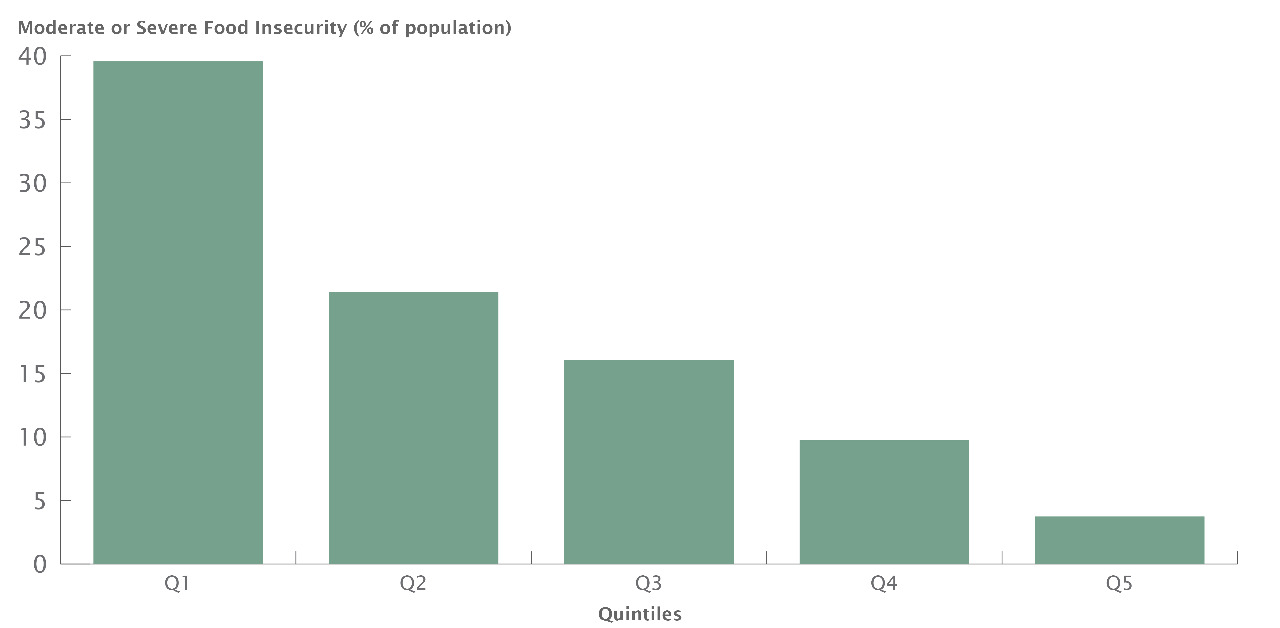

Unfortunately, 1 of 3 Pakistani households is food insecure. The problem is far graver in two of the four provinces, with 50% of households in Balochistan and 47% in Sindh facing food insecurity, in comparison to Punjab and Khyber Pakhtunkhwa, where those figures are 32% and 29% respectively. However, across all provinces one trend unsurprisingly persists—the rich face far less food insecurity than those in lower income brackets.

4 out of 10 of the bottom 20% of income earners (Q1) suffer from moderate or severe food insecurity. These numbers increased further during the Covid-19 pandemic.

Source: PSLM 2018-19, MP Analysis

Cause of food insecurity: Poverty

With close to half of households in the first quintile facing food insecurity, and around a fifth of households in Q2 and Q3 facing similar circumstances, it seems quite clear that there is a strong link between food insecurity and poverty. In fact, as explored previously, households in Q1 do not mathematically earn enough money to meet minimum nutrition standards, even if they spent all their income on food and nothing else.

To understand the wide disparity in food security and nutritional status between the poorest and wealthiest segments of society, it is worth taking a look at a breakdown of their food expenditure. Q1, the poorest 20% of households, spend proportionally more of their income on vegetables and rice than Q5. When it comes to wheat and wheat flour, Q1 spend nearly three times as much of their income on the staple used to prepare rotis, in comparison to Q5. So, it seems clear that the emphasis of households in Q1 is to consume carb-heavy, stomach-filling staples that can allow them to get on with their day.

On the other hand, Q5 proportionally spend far more of their income on nutritious and expensive items compared to Q1, such as beef (2x), fish (2x), mutton (8x), fruits (3x), milk, and chicken. It is worth remembering as well that this is in proportional terms, so in real terms, the disparity in rupees spent on these foods by Q5 compared to Q1 is even greater.

Other causes of undernourishment

There are also a couple other factors influencing poor nutritional outcomes in Pakistanis. The first is the lack of complementary feeding for children between the ages of six months to two years. Aside from breastfeeding, only 14% of children receive meals with minimum dietary diversity, 18% receive the minimum number of meals in a day, and only 4% receive the minimum diet necessary for optimal growth and development. Lack of awareness may be a factor in this, as many may not know that a child requires supplementary food beyond just breastfeeding. The National Nutrition Survey from 2011, for example, found that stunting prevalence was highest among children of illiterate mothers (38%) and lowest when mothers have above secondary school education (15%). However, educational status is also a proxy for wealth, so it may be that even this problem is fundamentally tied to issues of food insecurity and poverty.

The second cause is lack of clean drinking water. 56% of households in Pakistan drink water contaminated with coliforms, while 36% drink water contaminated with E. Coli, which can cause diarrhea that can be particularly deadly for young children.

Relief for the people

So, is there any way to move the needle on undernourishment in Pakistan? Well, the first step has to be the government providing greater assistance to struggling families to help them meet nutrition goals. Currently, less than 5% of Pakistanis benefit from social protection schemes such as subsidised food through utility stores and other nutrition programs. These could definitely be expanded. Argentina and Chile for example have both made substantial progress in this field over the past 50 years by launching programs focused specifically on maternal child health and nutrition. Another option that may be more efficient is providing a basic income to most Pakistanis. Within five years, BISP cash transfers of merely PKR 1000-1500 per family reduced wasting in girls by 11%, poverty by 7%, and increased meat intake among recipients by 23%. Such programs could be enhanced further in terms of their cash value and eligibility criteria.

Systemic reforms

While cash transfers and food subsidies can alleviate some of the nutritional challenges faced by Pakistani citizens, the only sustainable solution for the state in the long-term is initiating some much-needed systemic reforms in the field of agriculture. Specifically, our crop yields need to improve substantially. Our current yields per hectare for mainstay crops such as rice, wheat, cotton and sugarcane are only 29-52% of the per hectare yields achieved by the world’s best performing countries. That gap can be reduced through the use of higher quality seeds and fertilisers, giving farmers better access to credit to buy those seeds and fertilisers, and providing greater technical assistance to improve productivity, especially for those in the poultry and livestock sectors.

Alongside that, there needs to be greater awareness and cultivation of nutritionally-rich minor crops such as pulses, fruits, nuts and oilseeds. Pakistan is currently forced to import many of these items which places a strain on its current account deficit, as well as leading to higher prices in the local market due to their relatively high price in US Dollars. This would require a concerted effort on the part of the government to offer incentives to farmers to switch their production away from water-intensive subsidised crops such as sugarcane and rice, which Pakistan should already be transitioning from due to their excessive water demand and low price in the international market.

These are not novel solutions that I have ingeniously thought up while writing this article. The 2018 National Food Security Policy, published by the Ministry of National Food Security and Research, addresses many of these issues and then some more. As ever, the question comes down to implementation.