Water has gradually become a rare commodity for dwellers of both cities and villages. Water levels have significantly dropped since the 2000s, with the urban population rising and demand for food increasing. This is not a local, provincial or national challenge, rather countries around the globe are facing similar issues. Around 844 million people lack access to basic drinking water. Moreover, by 2050, at least 1 in 4 people will likely be living in a country affected by chronic or recurring fresh-water shortages.

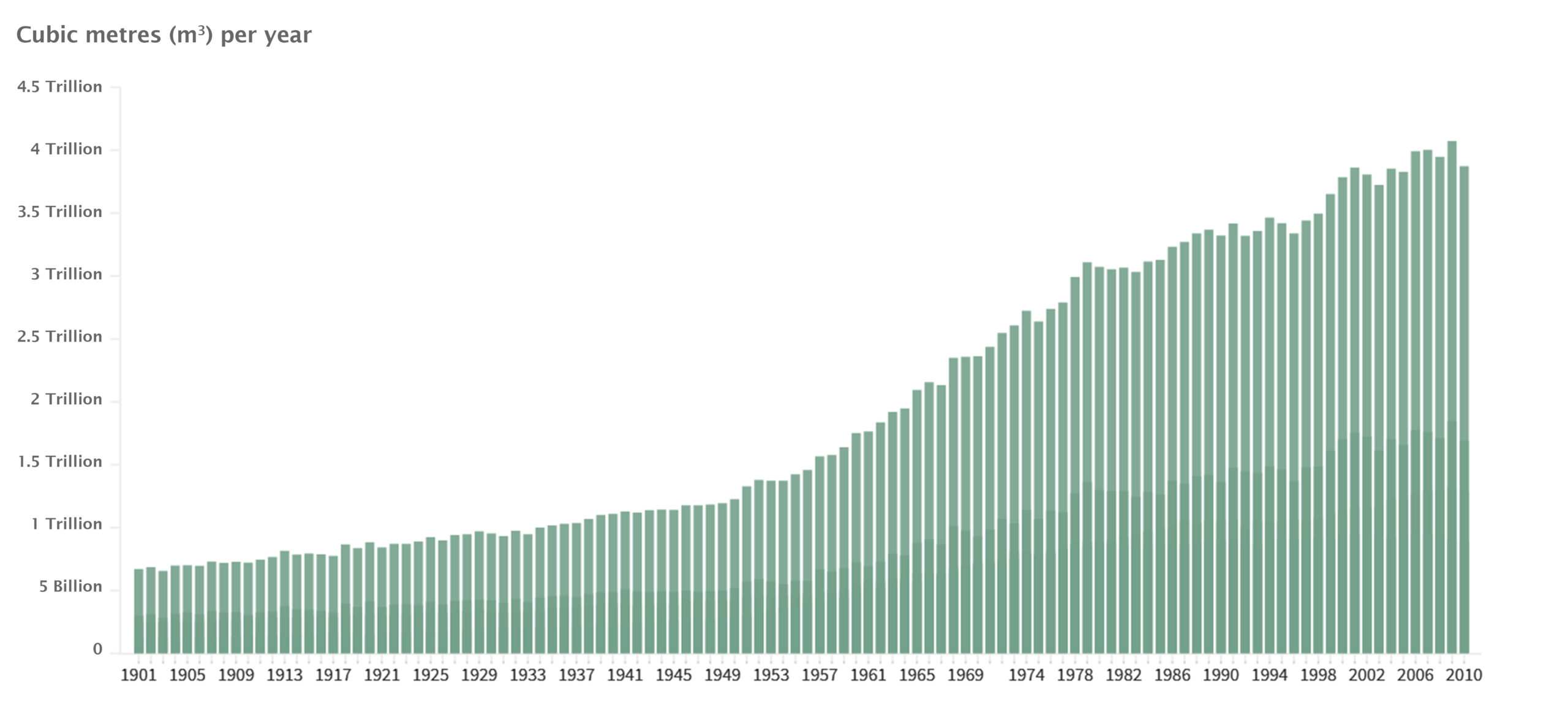

Global freshwater use for agriculture, industry and domestic purposes has risen rapidly in the last 50 years

Source: IGBP; MP Analysis

Source: IGBP; MP Analysis

Water Dynamics in Pakistan

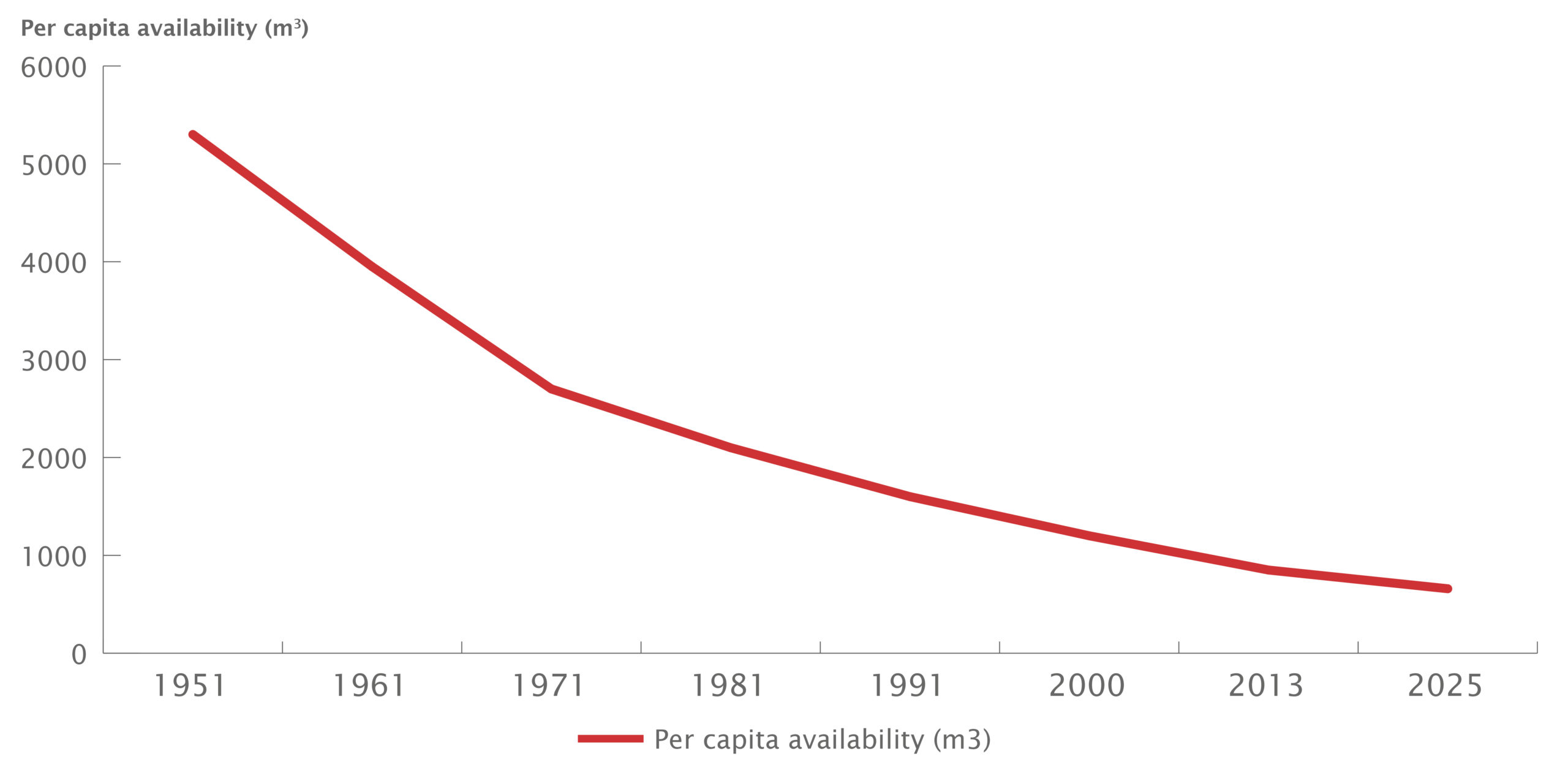

Coming to Pakistan, presently, the country is among the most water-stressed countries in the world with an availability of 1,000 m3 of water per person as of 2016. In the near future, it is distinctly possible that the number goes even further south to 860 m3 by 2025. These statistics depict long term catastrophic implications for the country in terms of environment, demography and food security, among others. Additionally, Pakistan’s excessive dependence on water with a hostile neighbor only adds fuel to the fire.

A growing population and inefficient use of water is driving a crisis of water availability in Pakistan

Source: WWF; MP Analysis

Source: WWF; MP Analysis

To cope with all these problems, Pakistan took a historic initiative with the introduction of its first-ever “National Water Policy” on 24 April 2018. The Council of Common Interests unanimously approved the 44–page document, which is set to be a guiding framework for the provinces to act upon, as they are independent to make their own decisions after the 18th amendment. It was decided that the policy will be implemented by the National Water Council. The federal ministers for water resources, finance, power, and planning and development, as well as provincial chief ministers, will sit on the council.

Criticisms of the National Water Policy

The policy was well-received by experts due to several key points, but also faced backlash for its silence on some very pressing issues. For example, it completely missed the issue of water shortage in urban areas, an issue that has existed for quite some time now. Major cities like Karachi, Islamabad, Lahore face water shortages year after year due to the creation of a political economy of water. The National Water Policy laid down no plan in this regard, contributing further to the deadlock on the issue.

The policy was also considered extremely nostalgic when it comes to understanding the contemporary dynamics of water. For example, it has yet not categorised the nature of water as a commodity or a public good. Water metering is another significant issue, as we are still in a time where we charge for water per square-feet, and not the consumption of a household. It is like charging fuel prices proportional to a vehicle’s size, rather than use.

Furthermore, the NWP brings with it more complications by neglecting some key strategic ground dynamics of water scarcity, in terms of its relevance to themes like food security and life expectancy. These issues are fundamentally interlinked to water, and more needs to be done to understand and realign our priorities, like reforming our agriculture sector in the face of a water scarcity situation.

The policy also completely misses out on setting any qualitative or quantitative targets, and also doesn’t contain any reference to Sustainable Development Goals 2030 of which Pakistan is a signatory. Additionally, it does not address how India can affect our agriculture, energy, and economic development by the manipulation of water through cross-border water shedding.

Provincial Action

Among all provinces, Punjab was the first to put in place its own water policy under the broader umbrella of NWP, through the Punjab Water Policy 2018. What’s more is the province has also set in motion legislation titled the Punjab Water Act in 2019, which will act as a substructure to set up the Punjab Water Resource Commission and Punjab Water Services regulatory authority to deal with all water-related issues.

Catching up with Punjab, in 2020, Khyber Pakhtunkhwa also introduced a law titled KP Water Act 2020. Under the act, a commission and authority will be formed, named the Khyber Pakhtunkhwa Water Resource Management commission and the Khyber Pakhtunkhwa Water Resource Regulatory Authority.

As for Sindh and Balochistan, both provinces have remained silent on the issue and have not yet taken any policy initiative. This is surprising as Sindh has often faced major water-related issues and registered complaints about its share of water. As far as Balochistan is concerned, it is obvious it has many socioeconomic constraints and has failed to bring any policy measures to the table that are comparable to KP or Punjab.

Inaction from the Centre

Fighting a water scarcity war alone without the collaboration of all the provinces is not an ideal scenario. In this regard, an official from the federal Ministry of Water Resources stated that the ministry can’t exercise any authority over the provinces for being inept, as the NWP merely serves as a broader guideline for all the provinces to act upon in light of the 18th amendment.

However, to achieve certain targets, the Ministry does engage its underlying institution, Water & Power Development Authority (WAPDA), which is mainly financed through the federal Public Sector Development Programme (PSDP). In the year 2019 and 2020, a total of 37,948.513 and 44,072.529 million rupees were released to the water resource division from federal PSDP.

The Ministry has also complained about a lack of evidence-based policy research under its wing, as most of the R&D of the ministry is outsourced. For example, Pakistan Council of Research in Water Resources (PCRWR) comes under the jurisdiction of the Ministry of Science and Technology. Other institutional bodies also contain water-related data, all of which need to be consolidated under one forum, in order to make an impact and understand the different dynamics of water.

Finally, as far as the performance of the provinces is concerned, there is a need for a proper instrument through which provincial priorities can be aligned with that of the federal government on the National Water Policy to push them in the same direction of progress. Only then can the policy be successful in achieving its goals over time.