No running water, a non-existent sewage system, and electricity for a few hours a day if they’re lucky. This is the reality of daily life for many of the 30 million Pakistanis estimated to be living in informal housing in urban Pakistan. In Karachi alone, around 10 million people live in informal housing, spread out over more than 2000 settlements set up wherever possible; from government amenity plots, to land designated for agriculture, to any privately-owned empty plots that can be squatted on.

If that doesn’t speak to dysfunctional government policy, then how about this—house prices have trebled in the last decade, as the country faces a housing shortage of more than 10 million homes. Meanwhile, the only meaningful response by the current government is a scheme that offers housing through a two-million-rupee deposit up front—in a country where the median urban household’s income is 34,000 rupees.

This should put to bed any misconceptions of why millions of Pakistanis live in katchi abadis, goths, or other forms of informal housing such as slums (terms that have slightly different definitions, but for the purposes of clarity will be used interchangeably in this article). For most of them, the prospect of owning a home is merely a distant dream; one that recedes further with each passing day.

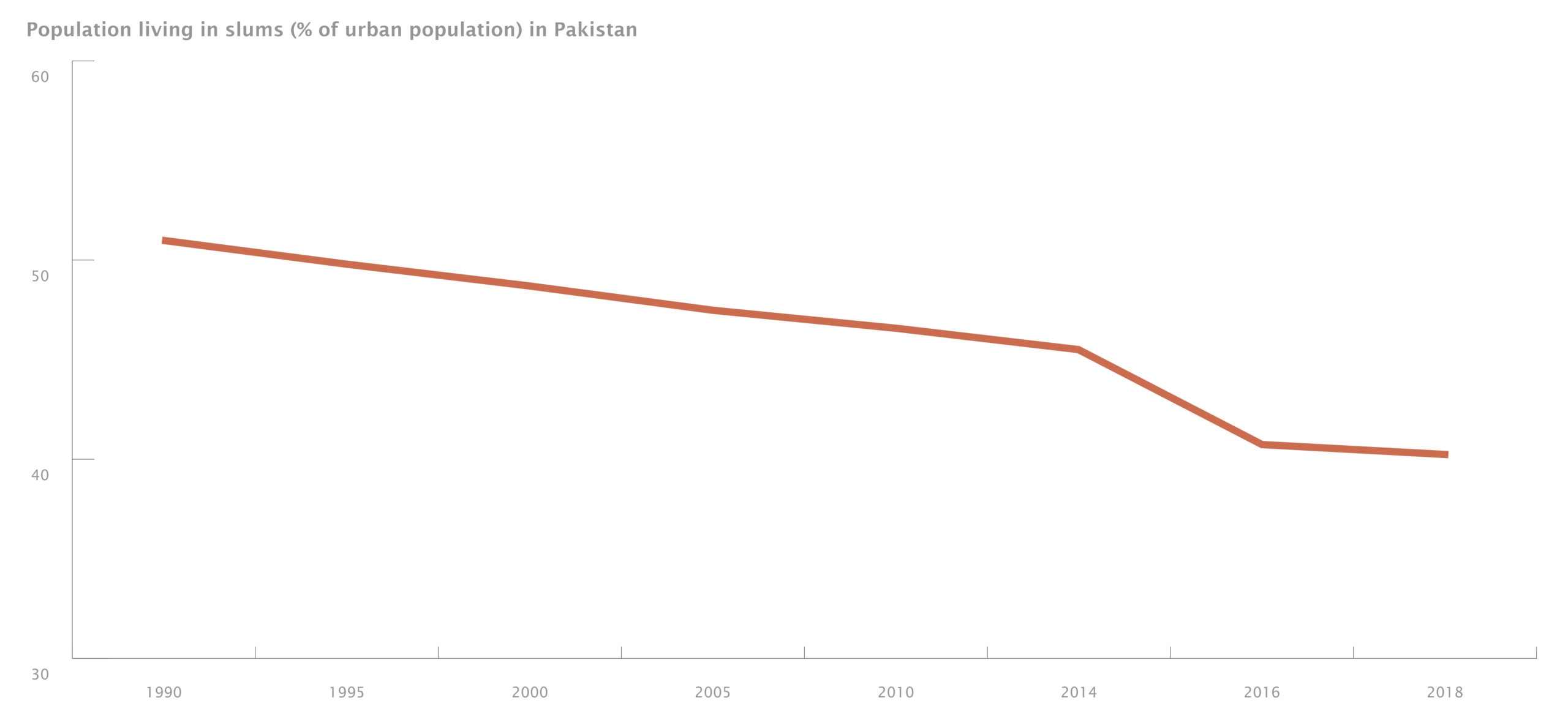

The percentage of Pakistanis living in informal housing has fallen since 1990, but still remains stubbornly high

Source: World Bank; MP Analysis

Daily life in a katchi abadi

Living conditions in katchi abadis are not ideal, to put it mildly. A case study of two unregularized katchi abadis in Lahore found that neither had utility-supplied water, only 30% of the residents in one abadi had a government-built sewage system, and government-built drainage was even rarer—serving only 16% of the residents in one of the abadis. These homes also suffer from structural issues and fire hazards due to poor quality building materials and proximity to other similarly unstable houses.

Katchi abadi residents have to navigate all this while also dealing with the harassment that comes on a daily basis by virtue of living in these settlements. According to Ammar Rashid, a researcher and activist who works with katchi abadi residents in Islamabad, “The junior landowning and administrative bureaucracy act as rent-seekers, regularly extorting money from residents to allow them to squat, build or gain informal access to some utility. Sometimes they threaten to demolish existing homes unless payments are made, or proceed with a demolition and charge money to allow residents to rebuild. Police detentions at local stations for petty offenses (and sometimes not even that) to extract bribes are also fairly routine”.

A story of government neglect

It is not as if the government doesn’t know that these people exist. In election season, political candidates and party workers can often be found canvassing katchi abadis for votes in return for utility connections or government employment. Rashid recalled one example where “a politician personally bought an entire electric transformer costing millions (something that is otherwise entirely the responsibility of the distribution company) in a katchi abadi in exchange for vote guarantees”. However, such developments tend to be ad-hoc and extremely irregular; after all elections only come around once every five years. Far more common is the theme that architect Arif Hasan noticed in Orangi Town, where politicians would come for receptions and make grand promises that would inevitably never be followed up on.

This neglect is well illustrated by the Government of Sindh, which has a Katchi Abadies Department, at least on paper. In reality, the department has been essentially non-functional for over three decades due to low funding. In the FY 2019-20, its budget was PKR 0.17 billion, less than 0.01% of the provincial government’s budgeted expenditure. And in the last 13 years, it has provided low-cost accommodation to a mere 636 families.

Demolitions galore

By contrast, when it comes to demolishing katchi abadis, the state is full of vigor. As this article is published, thousands of homes in the Gujjar Nallah area of Karachi are being razed to the ground—even though many of the affectees hold official leases for their homes from the city government (KMC). The law used to demolish these homes is the Land Acquisition Act of 1894, put in place by the British Raj to seize native lands. Even the colonisers had some standards though; Article 9 of the Act requires the government to give advance notice to residents about their lands being taken over for a ‘public purpose’, while Article 23(2) requires residents to be paid 15–25% above a court-determined market rate. Furthermore, Article 31(1) specifies that this payment should be made before taking possession of the affectees land.

In reality, the Pakistani government’s preferred technique seems to be to demolish first, ask questions later. Under activist and public pressure, the Sindh Government has belatedly announced plans to compensate some Gujjar Nallah residents whose homes have already been destroyed. Past evidence tells us however, that most will still not end up receiving any compensation.

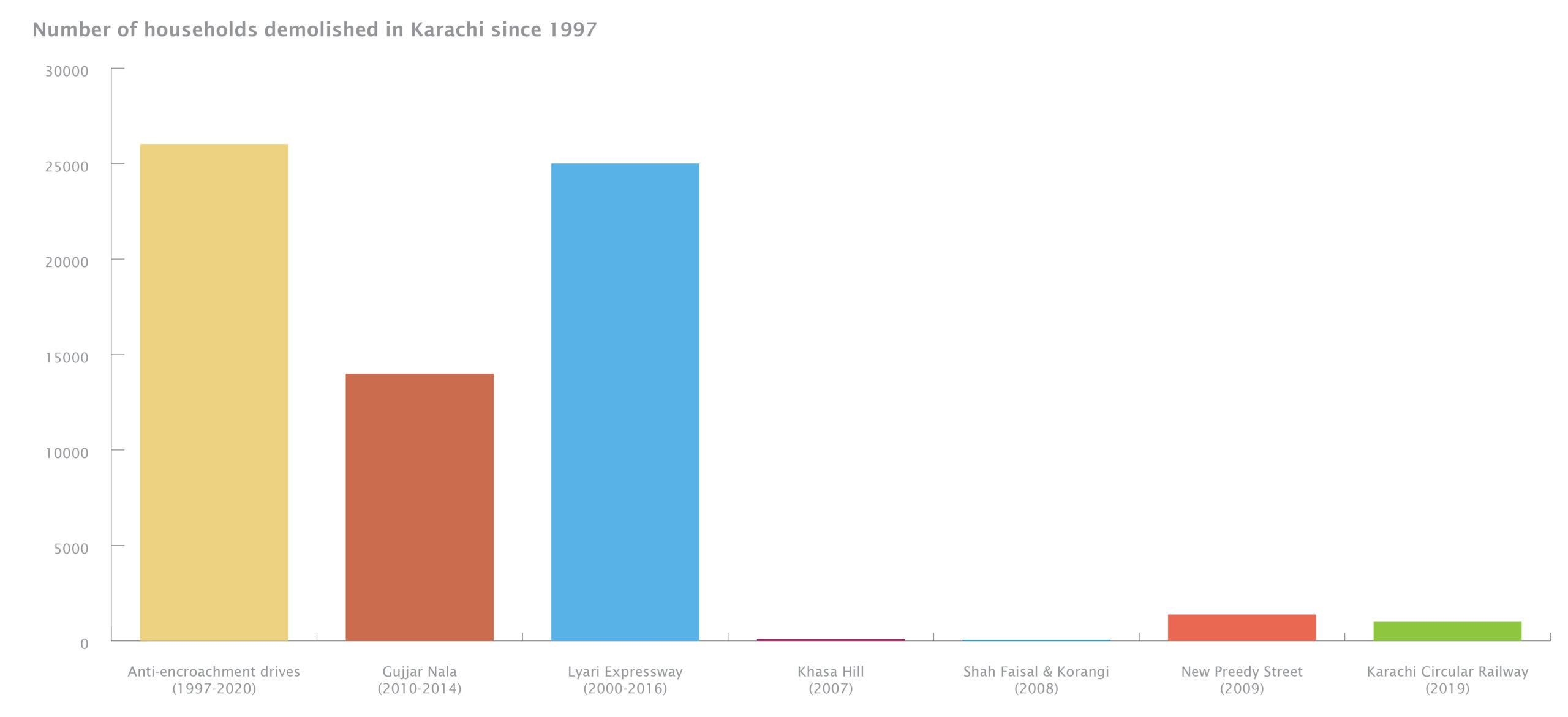

Since 1997, nearly 70,000 homes have been demolished in Karachi, rendering half a million people homeless. Less than 33% of the affectees were resettled or given compensation.

Source: Karachi Urban Lab; MP Analysis

It should be noted that a Supreme Court stay order from 2015 does offer some level of protection, as it prohibits demolitions of any katchi abadis built before that year. But it is not always adhered to by the authorities, and in some cases the Supreme Court itself has subsequently ordered demolitions, such as in Gujjar Nallah and the Karachi Circular Railway.

The way forward: Regularisation

There is another way to improve the quality of informal housing in Pakistan that, believe it or not, does not involve demolishing homes. It’s called giving people official land deeds for their houses, also known as regularisation. Muhammad Toheed, a senior researcher at IBA University’s Karachi Urban Lab, explains that this one step alone can make a big difference. “Tenure security is essential in allowing infrastructure development to take place,” he says. “Currently many utilities do not want to deal with katchi abadis because of their status as ‘encroachers’. However, once tenure security is guaranteed through leases, municipal authorities are more likely to cooperate with these settlements.”

That was roughly the blueprint followed by the Orangi Pilot Project. Established in 1980, it helped regularise more than 150 goths, and worked with local government agencies to provide them sewage and water facilities. OPP also collaborated with the community to improve the quality of cement blocks manufactured by the local thallas, which provided a cost-effective solution to improve the structural stability of houses in the area. Of 70,000 homes in Orangi, more than 2,500 benefit directly from using higher quality cement blocks each year.

Another case study of four katchi abadis with similar demographics in Lahore found that the two settlements that were regularised were better off on every comparable metric of service provision and satisfaction, compared to the two settlements that were not regularised (although it should be noted that correlation does not necessarily equal causation).

A flawed process

As the examples above indicate, the government is not unaware of the strategy of regularisation. In fact, under the Sindh Katchi Abadi Act of 1987, there is a process through which katchi abadis can be officially ‘notified’, which although does not give each home an individual house deed, it does give official recognition to the settlement’s right to exist. There are also a number of unnotified katchi abadis recognised by the provincial government, although they are on less sure legal footing as they have not gone through the notification process of obtaining NOCs from land agencies, and having their land ownership notified in a gazette.

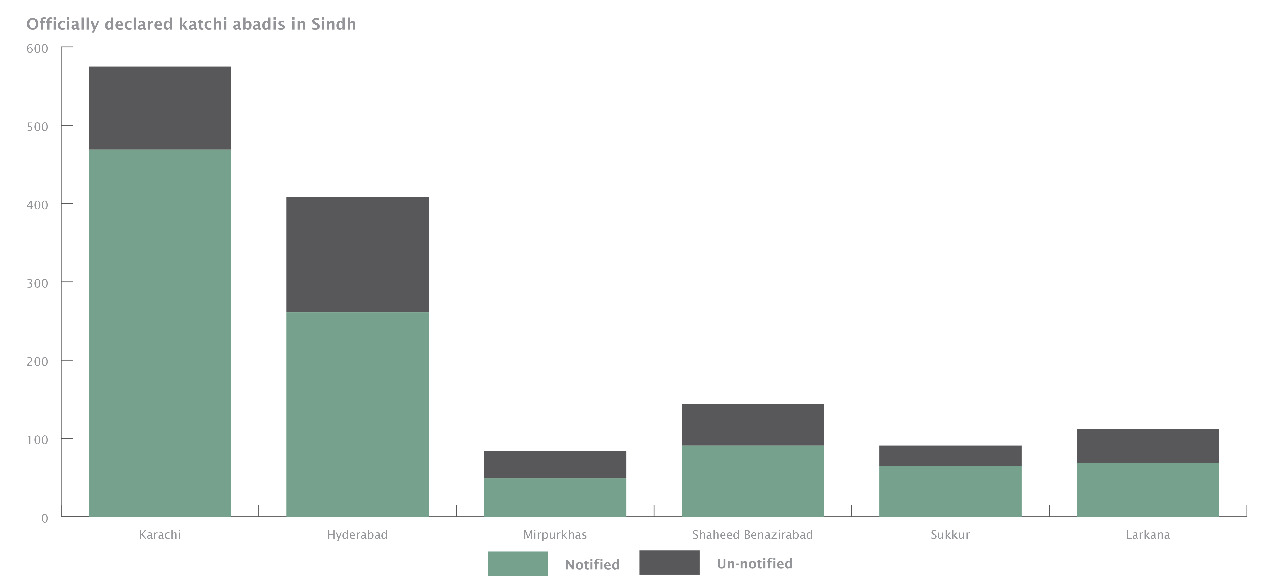

Still, so far, so good right? Unfortunately, there’s a catch. All this only applies to katchi abadis built before 1997, erasing the existence of a vast number of settlements that either cropped up in the last 24 years, or do not have the documentation to prove otherwise. In Karachi for example, the government recognises only 575 katchi abadis, despite OPP identifying at least 2,173 informal settlements in the city by 2011—and even that data is now a decade old.

The Sindh Government recognises a total of 1414 katchi abadis in the province. Estimates from the ground suggest there are more katchi abadis than that in Karachi alone.

Source: Katchi Abadies Department Government of Sindh; MP Analysis

Priorities, priorities, priorities

In contrast to the legal complexities confronted by katchi abadi residents, elite housing developments that break the law in Pakistan only face minor reprimands and a post-construction regularisation fee. Prime Minister Imran Khan’s own house in Bani Gala was illegally constructed, but new bylaws were introduced in 2020 which allowed him to regularise his house for a mere PKR 1.2 million. Meanwhile Bahria Town Karachi’s land grab, possibly the largest in the country’s history, did earn it a PKR 460 billion fine, but it also meant the project’s regularisation.

The court’s logic for allowing these regularisations is that action should have been taken by relevant land agencies against these developments before they were constructed. Now that they have been constructed and sold, the court reasons that cancelling the projects would cause a lot of loss to ordinary buyers. Even if we accept this line of reasoning, should the court’s logic not extend to katchi abadi residents who have invested substantial time, effort and money into their homes and surroundings?

This does not mean that regularisation of katchi abadis is always the right answer. For some, relocation and compensation may instead be necessary. However, in either case, the decision should be reached collectively via consultation with the affected communities. This was the strategy adopted by the Thai government, which improved informal housing by providing infrastructure subsidies and housing loans to community organisations, along with technical advice from government architects and academia. Similar initiatives have also been launched by governments in India, Indonesia and the Philippines.

Ultimately, it is a question of priorities. Is our government as invested in improving informal housing as it is in protecting the property portfolios of the elite?

I don’t know how long this romance and undue obsession with katchi abadis will continue?

Generally, a particular sector of society carry a pro slum sentiment that accepts every illegal approach into legitimate one to accept them. This is done with the influence of socialist backdrop that was very evident in generation that was born in 50’s and grew up in 60-70’s. While defending their sentiments towards these illegal settlements (termed as katchi abadi, to give a false sense of ligitamacy), the authors, activists completely forgot the rights of the one who is living in the formal, all legal and planned settlement. The ordinary citizen of the city, like me.

To stress their point, usually illegal actions and approaches of DHA, Bahria Town and Bani Gala are referred to. Such activists intentionally close their eyes towards the deprivation of land that was reserved for civic amenities like hospitals, schools, colleges and parks. All future planning space is consumed up by these illegitimate slum areas. What a pity, indeed!