Every year when the annual budget in Pakistan is released by the federal government, everyone becomes an economist and has something to say about it. Actual economists also talk about it. However, for someone with limited background on the topic, something like “Financial squeeze to cause education budget cut” takes center stage instead. Most are unaware of the division of responsibilities between the federal and provincial governments and are hence unable to properly interpret what the real story behind the breaking news is. In order to have more nuanced discussions on the budget in Pakistan, let’s first understand the macro overview of fiscal responsibilities.

Provinces need money

After transitioning to democracy under the PPP in 2008, Pakistan opted for a parliamentary form of government, which the 1973 constitution had passed into law. The delayed institutionalization of the law was mostly due to successive military coups and political instability in the country. Dictators prefer a presidential form of government, which makes them the ultimate authority and does not offer devolution of power to the provinces. The 18th Amendment allowed the hegemony of the establishment to end (at least on paper).

Along with this legal amendment, the money sharing mechanism between the federal and provincial governments, called National Finance Commission (NFC) Award, also changed. With more subjects such as health and education handed to provinces, they required a higher share of revenue to be able to deliver.

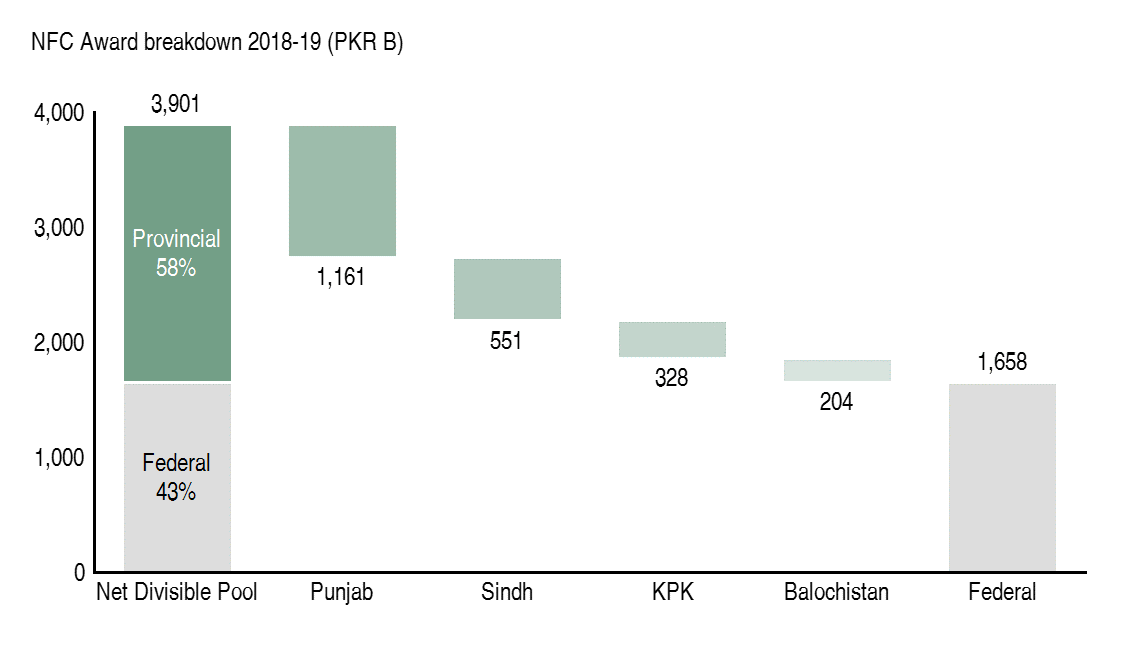

Breakdown of federal revenues allocated to provinces in Pakistan (2018-19)

The NFC is supposed to be revisited every five years but the one we are currently working with is still from 2010. Before that, provinces used to receive their share of revenue based on population alone, which unfairly disadvantaged Khyber Pakhtunkhwa (KPK) and Balochistan. Since 2010, majority of taxes collected by federal government are transferred to provinces based on select metrics in addition to population. Provinces receive 57.5% of the net divisible pool of revenues collected by the federal government, which is split by population (82%), poverty/backwardness (10.3%), revenue collection (5%) and inverse population density (2.7%).

While the largest share of the award is still based on population, the other metrics, though not perfect, have been a step in the right direction. The component of poverty/backwardness allowed provinces like KPK to catch up. The emphasis on revenue collection helped Sindh as it hosts a large tax-paying industry. The recognition of inverse population density allowed for a larger proportion of funds to flow to Balochistan with its low population but large land size.

Federation needs money

The NFC award is not perfect and needs updating. Division of responsibilities between federal and provincial governments are still not clear with Islamabad still housing structures of a few devolved ministries such as Ministry for Federal Education and Training and Ministry of Food Security versus the provincial counterparts on education and agriculture. There have been claims that federal deficits we have discussed previously were caused by increased provincial share of revenues. Some estimates put the negative impact of devolution on the deficit at 0.8-1% of GDP, which is not significant given the deficit has risen 9% of GDP in recent times.

Despite the devolution of power, the federal government still has many responsibilities it needs to carry out. Think of subjects like military that have to be centralized. Because it only gets 42.5% of the revenue it generates now, the federal government has had to borrow heavily in the past few years from domestic and foreign sources to make ends meet.

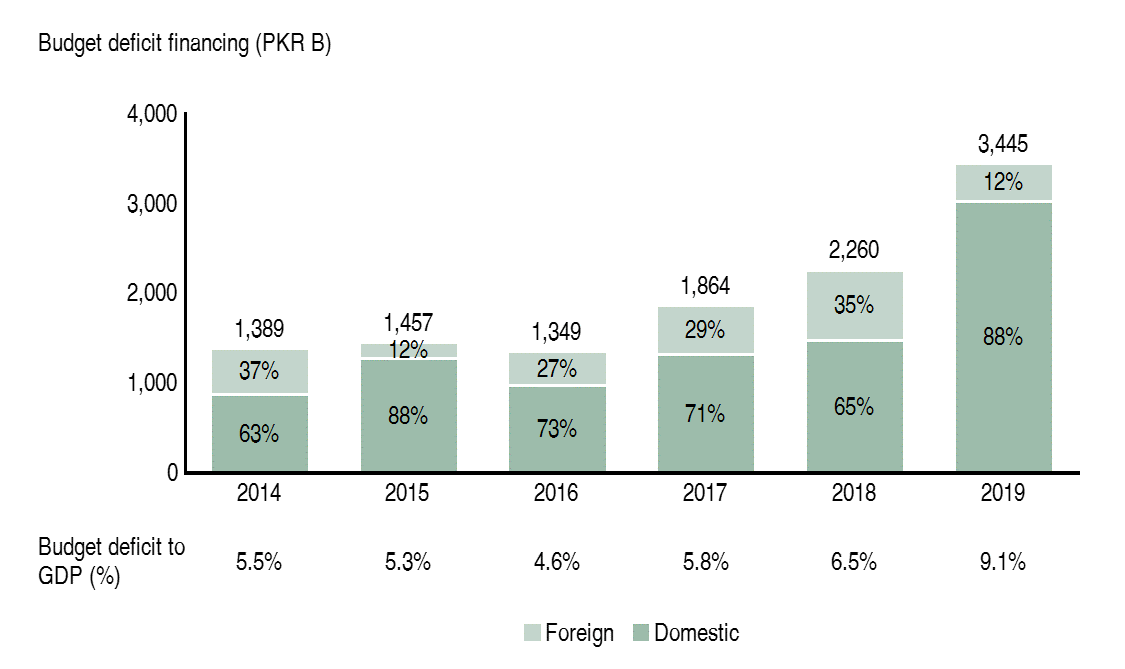

Financing taken by the government for supporting budget in Pakistan (2014-19)

As budget deficits have risen, the financing required to plug the gap has also increased. Note that the figures given above are specific to borrowing for budgetary support only. The government has also heavily borrowed from the rest of the world to finance current account deficits as we discussed in our first ever post. While the majority of borrowing for budgetary support has been domestic, in 2019, 12% was from foreign sources. Foreign loans, such as those we receive from the IMF regularly, have to be repaid in dollars. For this purpose, the country needs to generate dollars from exports, remittances or FDI in the country.

Government causes inflation

However, increased share of domestic loans in the past has also been problematic. Until May 2019, not only did domestic public debt rise, share of loans coming from the State Bank of Pakistan (SBP) also increased.

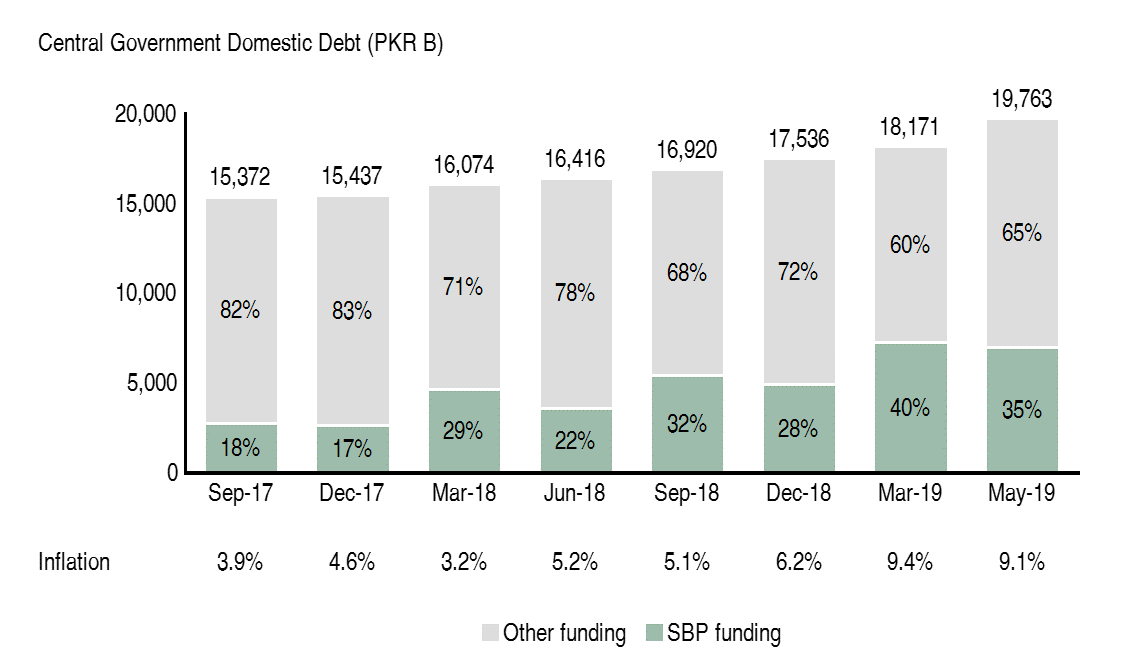

Share of Central Bank loans in stock of central government debt (2017-2019)

Borrowing by the government from the Central Bank leads to inflation. You can see the inflation numbers at the bottom of the chart rise from 3.9% in September 2017 to 9.4% in March 2019, in tandem with share of SBP funding. This happened because SBP provided funds to the government by printing money. If you print money, you will have too much cash chasing too few goods. To simplify, think of two people wanting to buy the same shirt. The shirt costs PKR 1,000, both buyers have PKR 1,000 each but only one shirt is available. If all of a sudden, there is more cash available to both of them, they will each try to outbid the other and the price of the shirt will rise.

The Central Bank printing new money to finance government deficits was by no means the only factor behind inflationary pressures in Pakistan. Everything we have discussed in the past ranging from low productivity, increasing demand and high input costs impacted inflation too. There are other points around conflicts of interest and short-term maturities of these borrowings that we do not have to get into but point is SBP borrowing was bad. After May 2019 and especially as part of the new IMF program, this practice has been restricted. There was actually a legal provision enacted as far back as 2012 to moderate SBP borrowing, but that was ineffective. Hence, this newfound restraint is welcome as it provides the Central Bank autonomy to carry out its functions effectively.

Loans to pay off loans

Now that we have spoken about the structure of the debt and its shortcomings, let’s talk about the reason behind this debt in the first place. Every new government comes in and blames the last one for taking on too many loans, which they have to repay by taking on even more loans. To understand this phenomenon, let’s review the federal budget in Pakistan.

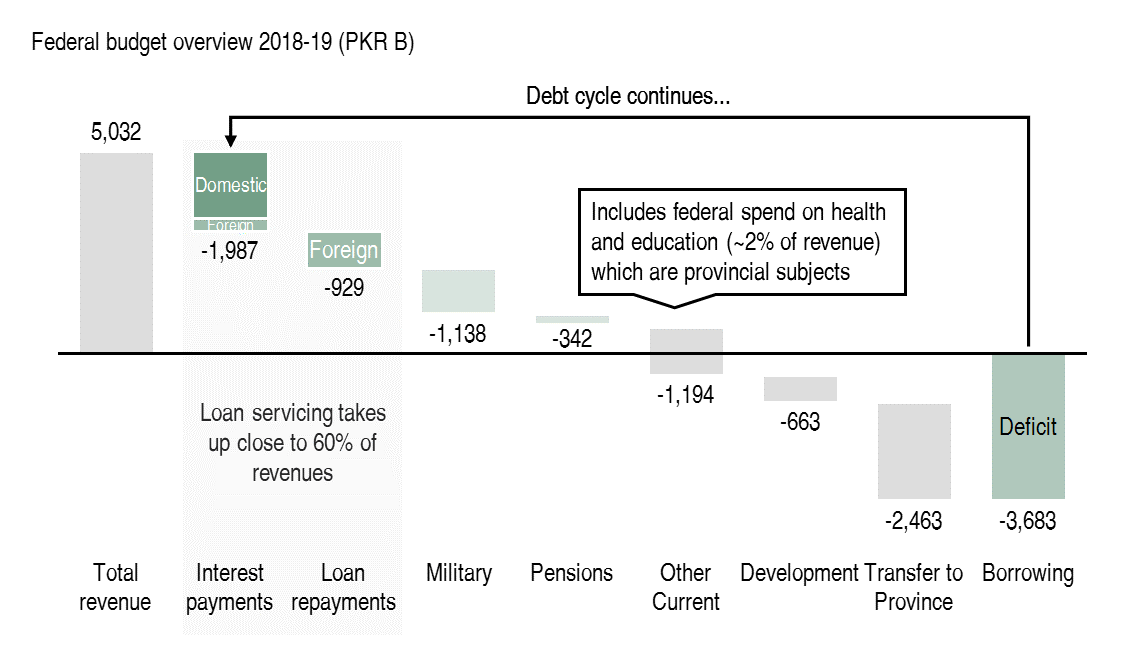

Breakdown of federal budget in Pakistan (2018-19)

Close to 60% of the revenue collected by the federal government, goes to servicing old loans. The servicing aspect has two components: interest payments and loan principal repayments. In 2019, out of PKR 5 trillion revenue the federal government collected, almost PKR 2 trillion went out in interest payments alone. Another PKR 929 billion was used up in foreign loan repayments. This is after PKR 2.5 trillion had to be transferred to provinces to abide by the NFC Award. The federal government itself is left with no revenue after these expenditures and hence has to borrow.

The borrowed amount goes toward military expenditures, which we will talk about in detail later. It also goes toward paying pensions, out of which the majority are also military related. The remaining amount is used to actually run the government, provide subsidies and grants as well as carry out development expenditures for public investments. You should now see why the federal government does not have the room to invest in everything under the sun that voters demand. Since revenue is limited, due to reasons we discussed last time, each successive government has to borrow to meet its expenditures. Then they need to borrow to service the debt they have taken on and the cycle continues, compounding each year.

We reap what we sow

Since the resources transferred to provinces after 2010 have increased, the central government expects provinces to better manage their budgets and provide the federation with surpluses. Provinces have also been given certain tax collection responsibilities, for example tax on services, to help with surpluses. However, resources are still limited for provinces and they are unable to carry out all the necessary expenditures they are responsible for.

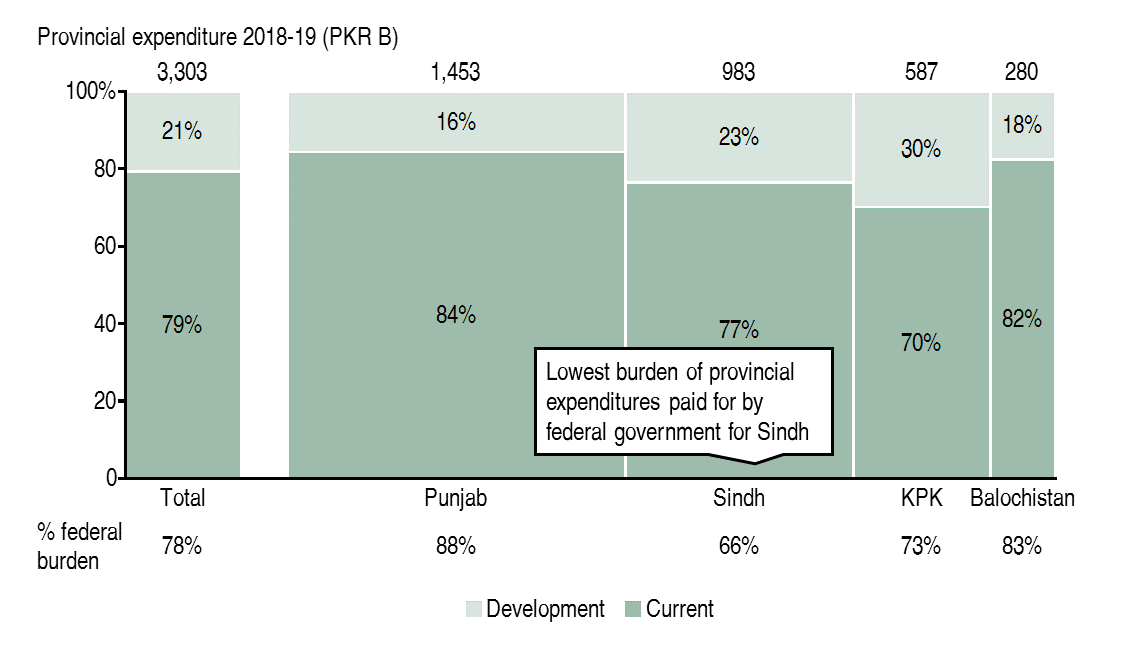

Breakdown of provincial budget in Pakistan (2018-19)

This is specifically true for development expenditure. At Macro Pakistani, we have tried to drive home the importance of investment repeatedly. However, like the SMEs in Pakistan cash-strapped to carry out everyday expenses, provincial governments also continually bemoan not having enough funds left over to focus on development. Only 21% of provincial expenditure is directed toward public investment while the rest is used to run existing functions of the government. In education, for example, because there is barely any money available to run current schools, there is no money left over to invest in new school systems for the future.

There is also disparity between how much money provinces receive from the federal government to finance these expenditures. While the NFC Award covers 88% of all of Punjab’s expenses, it only covers 66% of Sindh’s burden. That means the Sindh government has to finance the rest through its own tax collection and debt. Sindh, like every other province, claims its population is understated and that it should receive a higher portion of the divisible pool. While its arguments have merits, the whole premise of distribution of resources based on population needs to be revisited. India reduced the weight given to population in their finance commission to 25% and fixed the population to the shares in 1971. They did this to counter the perverse incentive provinces otherwise have of not working towards population control.

More power to districts

We have so far focused on the scarcity of resources at the federal and provincial levels and not much on how those resources are effectively spent. For effective governance, a complete devolution to the smallest possible unit of land is required. Think about a corporate group with four businesses. Each business has its own needs and requires resources accordingly. During a corporate budgeting exercise, all four businesses would ask their respective departments what their needs are. Those departments in turn would ask sub-departments and so on. In the end, what you will get is a bottom-up exercise, which takes needs at the smallest unit into account and escalates them up the hierarchy. Targets will then be set and tracked accordingly and each unit will be asked to deliver according to the resources they are provided with.

A parliamentary system is supposed to work the same way. With authority and resources trickling down all the way from the Prime Minister to a localized unit. However, in Pakistan, that devolution is yet to fully take place.

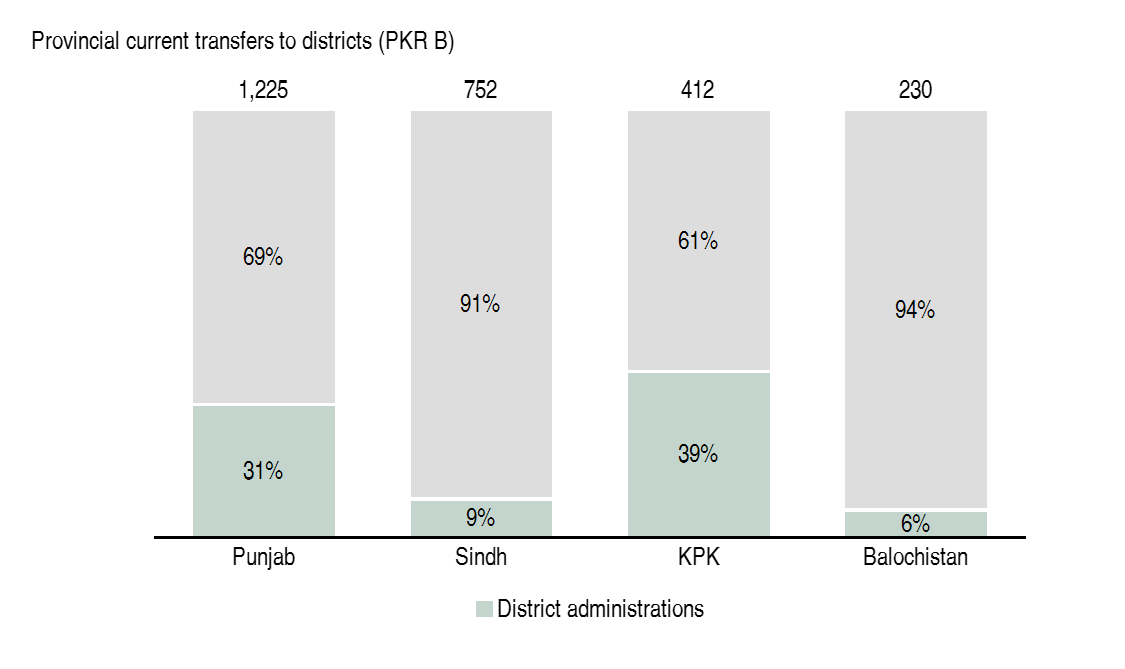

Transfers by provincial governments to district administrations and local governments (2018-19)

While KPK and Punjab allocate a significant portion of their budgets to district administrations and local governments, Sindh and Balochistan are yet to fully devolve their resources. Even in KPK, which has the highest proportion of district level transfers, over 60% of the budget stays at the provincial level.

Crazy Rich Karachi

Most Pakistanis would have heard of the woes the city of Karachi has had to face in the last decade. Which is why it is a good example to use when explaining the benefits of appropriate devolution of power and allocation of budget in Pakistan.

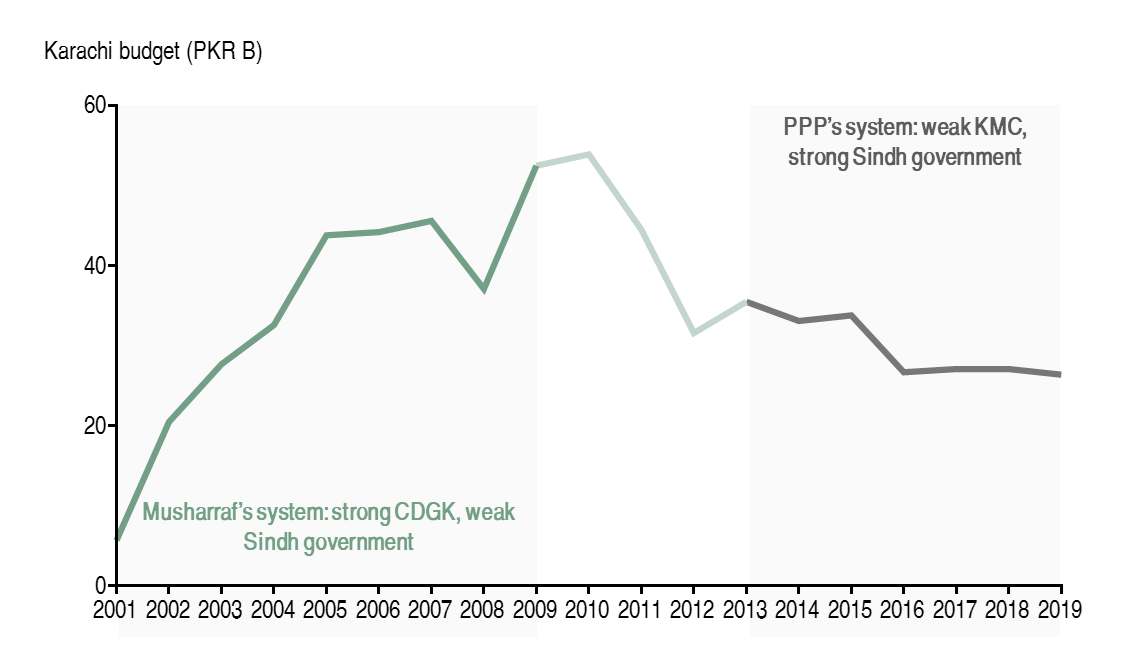

Historical city budgets for Karachi (2001-2019)

If you want a detailed account of the difficulties faced by Karachi, read the full article by SAMAA. But in short, if you go back 20 years, you will remember infrastructural development on the rise. This happened through a grant-in-aid program started by Musharraf called Tameer-e-Karachi. This was the autocratic way of doing development by giving funds tothe smallest unit of local government and telling it exactly what to do. We can debate whether all that asphalt was good for the city or not but at least citizens saw work being done. After Musharraf’s local government system ended in 2010, the budgets declined and urban infrastructure in the city deteriorated. When the democratically elected PPP came to power, they decided to strengthen the provincial government rather than continue empowering local governments. For readers who are not familiar with the situation, the result has been disastrous, with persistent issues with water, electricity, sewerage and most recently flooding. Lack of public investment is not just a Karachi specific phenomenon. Politicians and bureaucrats continue to undermine local governments across Pakistan to avoid ceding relevance. So while it is important to understand how money is distributed in Pakistan, it is even more important to understand how it is being spent. We will discuss how the country has performed on the devolved subject of education next time, to better understand issues with allocation of budget in Pakistan.

Good work guys.

Thank you Arsal! Please share with your network to help spread the word.

A great, informative write-up. I wish such an article would be included in the text books of school and college level books. I also wish it were also available in Urdu language so that common people would have understood.

Agreed Hamid! Plan is to democratize this information further by making it available in Urdu too. Hopefully with your support, we can make that possible in this coming year.